Document 10767823

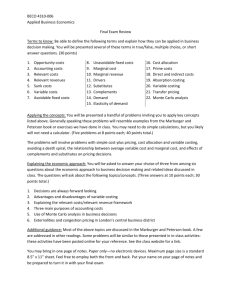

advertisement