The Ornamentation of Baroque Sonatas ... Sonata V for Bassoon and Harpsichord

advertisement

The Ornamentation of Baroque Sonatas Exemplified by Johann Ernst

Galliard's Sonata V for Bassoon and Harpsichord

by

Kristine A. Kohler

Honors Thesis (Honors 499)

Advisor: Homer C. Pence

Ball State University

Muncie, Indiana

April 12,1991

Expected Date of Graduation

May 4, 1991

1

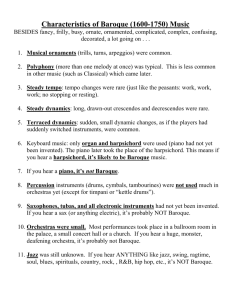

The Baroque era (c.1600-17S0) was a time of great beauty in

all of the arts. The architecture of the period, strongly inluenced by

Chirstopher Wren, combined beautiful arched ceilings with sculpture

and paintings. The arts thrived on the paintings of Rubens and

Rembrandt, the literature of Moliere and Locke, and the music of

Monteverdi and Bach. It was "a grandiose exercise in theatrical

illusionism, an overwhelming visual and even spiritual experience.'"

There was a freedom of expression in music and a spirit of

experimentation that mirrored the evolving scientific practice of

-

Galileo and his contemporaries.

Some of the original freedom in music came in the practice of

figured-bass, or thorough-bass. This is a means of notating

harmonic intervals above a bass note. Clavecinists were required to

realize these bass lines into four part harmony. This practice

started in France and spread through the rest of Europe. 2

The

individual keyboard players began to incorporate other

embellishments or agrements into their performance, and these

eventually found their way into other instrumental genres.

During the Baroque it was common practice for musicians to

1 H. Vyverberg, The Living Tradition: Art. Music, and Ideas in the Western World(San Diego:

Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publisher, 1988), p.300

H. Pence, Ornamentation of the Six Sonatas for Bassoon and Harpsichord by Johann

Ernst Galliard (Muncie. 1959). p. 24.

2

2

spontaneously improvise or embellish music during a performance.

Frederick Neumann in his book, New Essays on Performance

Practice, observed that many composers, such as Vivaldi (16751741) and his contemporaries, wrote out only the skeletal notes of

their works, particularly in slow movements. 3

In general,

performers were required to add their own ideas to complete the

music. There are, of course, instances where a composer would

include some ornamental suggestions or even write out a complete

ornamentation. Dart, in his book The Interpretation of Music,

described the musician of the baroque as being considered "a more

intelligent member of the musical community than he is now."·

Baroque musicians had to think and react quickly not only to the

printed page, but also to the people with whom they performed. In

addition to enhancing the printed music, performers copied each

other as they played similar phrases. There was a constant

interaction between musicians.

Although Baroque musicians found embellishment to be second

nature, that performance practice has all but disappeared today. At

that time, students heard their teachers and other more experienced

3 F. Neumann, New Essays on Performance Practice (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press,

1983) p. 149.

• T. Dart, The Interpretation of Music (London: Hutchinson University Library, 1967), p. 14.

3

players ornament melodies. Students copied the style of their

teachers until they were able to ornament freely on their own. This

can be compared to the jazz musician of today. Hearing a specific

"lick" or progression that he likes, a jazz musician will remember

it. Later he can use it himself and incorporate it into the traditional

practices. In this way a musician of any period can develop his own

style.

Before embellishing a piece of music it is important to

determine the origin of the composer and the style in which he

composed. Johann Ernst Galliard (1687-17 49) composed in the

Italian style. His first teachers, Farineli, and Abbate Steffani were

great influences on him. In fact, some critics of the day considered

Galliard's music merely a replica of Steffani's style. 5

The influence

of the Italian style is also indicated by Galliard's use of the Italian

language in his titles and tempo markings. He uses siciliano,

allegro, and adagio as opposed to the comparable French markings. 8

The first movement of Sonata V is marked adagio, the second and

fourth movements include allegro in their titles, and the third

movement is entitled "Alia Siciliano," all of which come from the

5

J. Marx, ed, Six Sonatas for the Bassoon with Thorough Bass for the Harpsichord(New

York: McGinnis & Marx, 1946).

• T. Dart, op. cit., p.93.

4

There are some general areas where ornamentation was used in

Italian-style music of this time.

Dart lists four: "extemporized

embellishment of adagios; optional variation on repeated material;

additional ornamentation at cadences; and slight alteration of

written note-values."7 After determining the area to embellish, it

is important to understand the different possibilities in

ornamentation.

There are many different types of ornaments that can be used

when embellishing a piece of music. Notes which are a third or more

-

apart can be connected by means of a glissando, grace notes, or by

outlining a chord. When filling in between two notes the fillers or

grace notes may be diatonic or chromatic. Either may be used in the

case of unaccented passing tones because the dissonance created

will be barely noticeable. s

Another type of embellishment is the trill. The trill can be

primarily melodic, or it may have a more important harmonic

function such as in a cadential trill.

In the first case the trill may

be started on either the main note or the upper note. For cadential

trills it is customary to start on the u'pper note. 9

This tradition of

'T. Dart, op. cit., p. 88.

a R. Donington, A Performer's Guide to Baroque Music (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons,

1973), p. 179.

'Ibid., p. 195.

5

trills it is customary to start on the upper note."

This tradition of

starting on the upper note has been passed down through many

generations of teachers; however, Frederick Neumann disputes this

idea. He contends that in Pier Tosi's Observations on a Florid Song,

translated by Galliard, Tosi implies that the trill should begin on the

lower note. The trill, Tosi says, is a rapid alternation of two notes,

II

one of which deserves the name master note because it occupies

with greater forcefulness the site of the note which is to be trilled;

the other sound, notwithstanding its higher location, plays no other

-

part than that of helper."'o

Regardless of Neumann's opinion on this

passage, Galliard wrote all of the trill examples beginning on the

upper note. Even if this was not Tosi's intention, this is obviously

what Galliard was accustomed to hearing.

Another very common ornament is the appoggiatura. This

ornament comes on the beat; it may be prepared or unprepared, but it

usually lasts half of the value of the note to which it resolves."

Galliard wrote that, when it is prepared, the preparation for this

ornament should be longer than the actual appoggiatura.'2

i

After

Ibid., p. 195.

10 F. Neumann, Ornamentation in Baroque and Post-Baroque Music (Princeton: Princeton

University Press, 1983), pp. 345-346.

11 Donington, op. cit., p. 180.

12 Dart, op. cit., p. 79.

6

gathering this more specific information, it is possible to begin

embellishing.

In his Performance Practice Neumann warns that, in general,

it is better to include too few ornaments rather than too many. If

the melody is a good one to begin with, it is able to stand alone, and

too many ornaments could clutter it. 13 Keeping this in mind, as well

as the general practices of ornamentation used in the Italian style,

one may begin to work with a specific piece such as Sonata V for

Bassoon and Harpsichord by Johann Ernst Galliard.

The first movement is marked "Adagio," (Appendix A), which

gives significant opportunities for embellishment as suggested by

Dart in his previously cited list. In examples *1, *4, and *5 notes

were included to fill in between thirds. The original version is on

the left and the embellished version is on the right.

*1

*4

F. Neumann, New Essays in Performance Practice (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press,

1989), p. 178.

13

7

*5

Example three also fills in between two notes on the third

beat, but it outlines a C major chord rather than by diatonic motion

as the previous examples do.

*3

*2 and *6 are examples of cadential trills.

*2

t>=~ I

frfEr; i' p I

f

*6

tl:~ I f

i'

P

mp

ro r I

Each of these trills, as will as the other trills in this piece

begin on the upper note. This decision was made in order to be

8

consistent with Galliard's examples in his translation of Tosi's

Observations on a Florid Song.

Example seven is only a slight variation on the already printed

music. The already existing trill is moved one eighth note early.

This is the fourth suggestion for ornamentation in Dart's list.

*7

.".

2:~ I t t rEt

,~ I

'Il"

r 1(1 r t

The only changes made in the "Allegro e Spiritoso" were the

addition of three cadential trills: *1, *2, and *3. These may be seen

in Appendix B and are self explanatory.

The "Alia Siciliano" (Appendix C) was originally written as

two repeated sections of eight bars each. In this copy the repeats

are written out in order to include the ornamentation which occurs

only in the second time through each section. Varying repeated

material was also suggested by Dart. Cadential trills, which have

already been discussed sufficiently, were added at *3, *5, and *7.

Another trill was added at *1, but it is a basically melodic trill.

2:~ a

crf F g I

9

*4 and *6 could also have been written as grace notes.

*4

3

*6

3

-

It is important to note that the rhythms indicated above are

approximated. Rosalyn Turneck, in her introduction to Putnam

Aldrich book Ornamentation in J. S. Bach's Organ Works, correctly

recognizes that ornaments were not precisely notated. She adds, it

is of prime significance to understanding the psychology

underlying the usage of embellishment symbols. To see

embellishment notation as an exact orthography is to impose

rigidity upon this florid art. The very essence of musical

psychology from which embellishment emerged and developed

is non-arithmetical and non-precise, unlike the mechanistic

frame of reference of the nineteenth century and the

tyrannical categorization-processes of the twentieth.14

*2 could be considered an upper neighbor or an appoggiatura.

-

Up. Aldrich, Ornamentation inJ.S. Bach's Organ Works (New York: Da Capo Press, 1978),

p. iii.

10

The fourth movement "Allegro Assai" can be found as Appendix

D. After considering the tempo and the lack of opportunity for

ornamentation, there were no alterations made to this movement.

Considerable thought was given to this project, and the results

of the ornamented version may be heard on the included tape. This

performance took place as part of the writer's Senior Honors Recital

on January 28, 1991.

Many musicians do not know where to start preparing for an

authentic performance of a Baroque work. They do not understand

that "ornamentation is not a luxury in baroque music, but a

necessity.,,15

It has now been made clear to this writer what some

of the preliminary steps in this process of ornamentation should

include. First, it is obligatory to determine in what style the

ornamentation should take place, either French or Italian. After

gathering some background information on the work, it is important

to understand the appropriate places to include ornaments. Dart

supplied a good general list to work from in his book The

Interpretation of Music. 1 !

There are also many traditional ornaments that were used in

the Baroque. Some of the most common are grace notes, trills, and

IS

Donington, op. cit., p. 160.

11

see p. 3.

11

appoggiaturas. Some ornaments occur more regularly at certain

times in music, but the most critical judge of what ornament to use,

and where, should come from the musician's ear. Musicians of the

Baroque needed very little time to plan their ornamentation if they

had time at all. They merely played what sounded right. With the

information found in this paper and a good ear, any musician may

make a satisfactory embellishment of a Baroque work.

Bibliography

Aldrich, Putnam. Ornamentation of J. S. Bach's Organ Works. New

York: Da Capo Press, 1978.

Dart, Thurston. The Interpretation of Music. London: Hutchinson

University Library, 1967.

Donington, Robert. A Performer's Guide to Baroque Music. New York:

Carles Scribner's Sons, 1973.

Marx, Josef, ed. (keyboard realization by Edith Weiss-Mann) Six

Sonatas for the Bassoon with a Thorough Bass for the

Harpsichord. New York: McGinnis & Marx, 1946.

Neumann, Frederick. New Essays on Performance Practice. Ann

Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1989.

Ornamentation in Baroque and Post-Baroque Music. Princeton:

Princeton University Press, 1983.

Pence, Homer. Ornamentation of the Six Sonatas for Bassoon and

Harpsichord bu Johann Ernst Ga Ilia rd. Muncie: Ball State

University (unpublished thesis), 1959.

Vyverberg, Henry. The Living Tradition: Art, Music, and Ideas in the

Western World. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich,

Publishers, 1988.

Appendix A

Sonata V

Johann Ernst Galliard

ed. Kristine A. Kohler

1687-1749

Adagio

~.

··

;t

B: _

•

-..

~

;.

-

p

~

~

.

f'!L

1L

l!rr

p

I'

-

...

I

A

··

I

i

-

....

t

I

I

Dr

~~

...

~

.-

1

I

*1

f

~~-rF~~~~~~

l~~~~~~

*3

.fC-~ ~

~.

.z.

.~~

•

L1.

~

-

3:,t.

""1

~

-.!':

IIiiIIIIIIL

"-liliiii

~

-

r

I' p r·

:1.

L.Z.":

r-

1

i

•

~

~

-j

r_r r r

Tl

I

p

~

•

-

-

-

t r

r~

IIIJ

I

-

-

*5

dim.

~~~~~~~~

~~~~~dtm.~~~

*6

··

,..

~

,.

-fI-

I~·

-fI-

~

,.

t:

-

,

I

I

r

It)

tJ~1

··

I

r

1

I

I

r

I

t\

1

D

r

mp

--

•

'in'

I

mp

-

"'

*7

~~~~~~

- ~~~~~~

,......,

I

Appendix 8

Allegro e Spiritoso

h.. 1*" _

··

I

I

~

4111

I

.

4!

4!

••

,~

I

··

.

I

··

~~~kl1 ..

.

I

Iv

~

.

.

-

b~

.

.

1nf

.

.-

-

illI

I

I

I

~

It}

I

r

I

---.

~

I

··

~

.

I

I

~

~

I

~

~J:

-t

I

•

I

I

*1

··

~

~1*"

.p-

~~~f:ft~t

_fl-_

-

b.

:A:

1*"!- ~

p

,

It)

11if

I

r

.IlL

·· -

.u...

r

I

4!

-

.

.

fl-

~

p

I

.

b~

""

. .

. 11if

-

111

··

~-F-~~

b.

- - . - . . . -,J-

~

.--

I

..

•

I~

··

··

q c-i

-" -

·· ··

--::e:

I

~~

r

"

··

_ h.

·· ··

·· ··

-d

··

r

~

-j

1

j

It}

~

-f'-

~.

.

JJo

-

-=

-

..,..

-

iiff

.

.J

.

··

-

ql

..

1

cresco

.

-,J-

!II- _

~

-

cresco

~

~

1lff

.

-.

r

•

'1

~

.

I

.

.

q -j

...

f

~

It>

,

,.

-

::-.....

l'" ....... ,...-

~

f

_

I

I

I

...

~

h. _

~ ~

JJo

"

-

I

t=

··

I

f:.

~

I

I

,

ItJ

··

'.

~

1'- ~ "' ..

.

lrt

k.

~

1

~

~

~...

~

JIo

I

I

I

.....

I

.

_.1*-

JIo

~ ~

I

1

~

*2

··

b.

1*-

~

".

~ f:. 1: f:.

f:.

pp

P

I

1_

I

.J

ie)

...

q"i

...

pp

p

..

··

...

t

··

~~ f:. ~~

I

I'l

~

i tJ

p

··

-(I-

I

I

I

I

. .

.

1*-

-f'-

-

~1*-~~

~

•

-

I'

.....

I

~

.

,.

.

f'-1*-

I

~

.

.

-

I

•

0:.

"It

:v

•

~

-

T

-

a

.....

...l.

~

/'

I

I

.

I

\L

I'

::1.

'J.

LL

P

0

•

..~

i

==t

==-'

=-

k

~

~

~

--r

I

-...

1

~

....

-

t-

*3

I

~

Appendix C

AHa Siciliano

-

··

~

~~

fL

k.

_

b~

)~

-1""=1

........,

I

=1

•

'"

...

I

r

It

Jt

I

,.

...

1

" "[ r

"

p

r'lr

...

I

"..

':;r

~~

r -p

·

~.

-1

If"

'p

1m)

*1

*2

··

f:-.

~

1:1'

~ fl-.

~~

.-

)b.-

=t1

""l

I

1'\

I

It

~r:

··

_.

r

'p

I

a..

-"'-

~~

,.

I

r

~

I

[

.

r r

~r

..

~

~.

*3

~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~

it~ 0..

~

t-

.fI- 0~ .fI-

"

,..

~

0

~

.fI-0~~ ~

~

Lo

~Z

.

t\ I

~

I

[jII!

rlflii.

LZ:

ItJ

~

I

T

--....-

~

r

~

~f:

_0

D

r

r r

o

o

~

,.0

'Io

1

,..

T

::10

~o7' ~

r

II'-

I-

~

•

T

to

~

m~ ~

.-

~

:..Lo

...l1

I

I

0

r

Ie.

~

r

0

t

O

r

~

~

I

0

0

~)

...

••

r

~

or

.

t\

-V- •

I

I

-

..

D

~~

..

~

0

"

I,. ~ ~ ~

*4

-(1-"

~

~

"

--£-. ~

-fL1tf. ,.

)

3

~

A

~r

tJ

~[li

."

f:

~

~

r Dr'

r" r

~~

y

~

-

,.

I

*6

*5

."

I

I..

~~

~

~"

~

t'ff-

~ C". ~~

~-

~~

3

,

f

;tJ

~

r

t

r'

I

""

:Jl

*7

,..

-,

I

~

r

~

pr

~

.-

1\

~

•

I

I

""

D

.

I

...

P

Appendix D

3

3

f

~

j

I':

-

~,.~ ~~

j

-

~.~

3

P3

"

..

f!:.71 ~-• ~ -".....--.

~

~

-

3

3

3

1

3

3

m r-T-, _

I

I

··

~

•

T

T

»

·· ··

-*

I

»

it)

r I

··

r

"3-

[-r i

-

~

. "i

J:

It>

-"

3

--

-

3

j

»

l~

-i

f

!'-

.

!'-

I

I

4!

4!

.

I

I

I'-

I

-l

··

~

-

.

.-

I

.

·· ··

-*

........

I

.

f

3

3

~

-·

·· ··

-:J

·

-l

I

I

"»

I

f

-

I

I'

1'1

-

orr

•

ItJ

•

T

.t!'

.

,,,

,

»

I

~~.~

I.J

3

»

II

I.J

I

3

I

I

u

•

..

•

I

»

»

»

t>

I

I

,

dim.

.

3

-

3

3

r I r lfP

• 3

.

f'-

~f'-1:

p

It

··

.---•

3

3

!It

_

3

~

r_r T I r '[I- r

-.

I

I

~

7T~

r

I

:

»

'\ »

--.

~

I

-

3

........

I

I I I

t

Iv

3

1$

I

3

··

•

"f'-~~_

It>

II

3 dim.

3

3

.p..

··

~

.1;-fit~ ~

~

3

I

I

r

r

r rJ !III!!!::

_

L

3

3

3

~~~~~~~~

~~~~~~~~

JJ.~

-('-

-('-

-(t-

.fi~.

-

~

~

'I"Ito.

lL

It)

l'Ii

:.I

3

f

I

I

I

l'

~

,

~

t.>

f

L

-

-

-

3

3

3

3

I

3

I

•

v

f-_

I

J

~

I

-

it.>

,

3

3

.........

-3 -

~

--

---

-

3

3

~

~

•

it.>

3-L-

.

P

L

I

"--'-J

3

3

3

.........

-

BALL STATE UNIVERSI1Y

COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS

SCHOOL OF MUSIC

KRISTINE A KOHLER

bassoon

in a

SENIOR HONORS RECITAL

assisted by

Kuniko Fukushima, piano and harpsichord

Don Rentfrow, cello

Sonata V

Adagio

Allegro e Spiritoso

Alia Siciliano

Allegro assai

Johann Ernst Galliard

Concerto in F Major, Op. 75

Aliegro rna non troppo

Adagio

Allegro

Carl Maria von Weber

(16S7- 1749)

( 1786-1826)

. . . Intermission . . .

Willson Osborne

(b. 1906)

Rhapsody for Bassoon

Sonatine pour Bassoon et Piano

I. Allegro con motto

n. Aria, Largll cantabile

Ill. Scherzo, Presto

Alexandre Tansman

(b.l897)

Kristine Kohler is a student of Homer Pence.

She performs with the Muncie Symphony Student Woodwind Quintet

and is a member of Pi Kappa Lambda, Nlltional Honor Society in Music.

This recilal is presented in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the Honors Program at Ball State University.

PRUIS HALL

Monday, January 28. 1991

8:00 p.m.

Series XLV

Number 91

In keeping with cllpyr;ght and crlist agrecml.:nls, U~I.: of recording and

photographiL: devires is not ~rl'litled by other than approved university

personnel. 'Ne request your cooperation.