Electronic Journal of Differential Equations, Vol. 2012 (2012), No. 37,... ISSN: 1072-6691. URL: or

advertisement

Electronic Journal of Differential Equations, Vol. 2012 (2012), No. 37, pp. 1–10.

ISSN: 1072-6691. URL: http://ejde.math.txstate.edu or http://ejde.math.unt.edu

ftp ejde.math.txstate.edu

A NON-RESONANCE PROBLEM FOR NON-NEWTONIAN

FLUIDS

OMAR CHAKRONE, OKACHA DIYER, DRISS SBIBIH

Abstract. In this article we study a highly nonlinear problem which describes

a non-Newtonian fluid in a specific domain (symmetric channel). This fluid

is subjected to pressure of known differences between two parallel plates. We

establish the existence and uniqueness of a weak solution. Our solution method

is based on a minimization technique when the nonlinearity is asymptotically

on the left of the first eigenvalue of the operator k-Laplacian.

1. Introduction

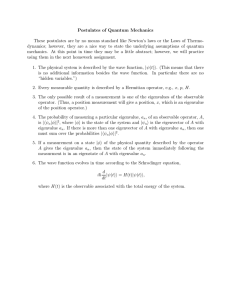

Let Ω ⊂ R2 be a bounded domain with boundary ∂Ω = Γ = ∪4i=1 Γi , where

Γ1 = {0}×] − 1, 1[, Γ2 = {1}×] − 1, 1[ and Γ3 , Γ4 are symmetrical to the x-axis,

see Figure (1). In the interior of this domain, a non-Newtonian fluid is subjected

to pressures of known differences between the two sides Γ1 and Γ2 .

~ k u = (−∆k u1 , −∆k u2 )T ,

We note by u = (u1 , u2 )T ∈ (C 2 (Ω) ∩ C 1 (Ω̄))2 and −∆

k−2

where −∆k ui = −div(|∇ui |

∇ui ) is the operator k-Laplacian i = 1, 2 and 1 <

k < ∞, which is a nonlinear operator, (if k = 2, there is the usual Laplacian). ∆k

has been used on Sobolev spaces by several authors we cite for example [3, 4], we

extend some results of existence and uniqueness relative to the first eigenvalue of a

Stokes problem. Let p ∈ L2 (Ω), we note ~g (x, y, s1 , s2 ) = (g1 (x, y, s1 ), g2 (x, y, s2 ))T ,

where (x, y)T ∈ Ω, (s1 , s2 )T ∈ R2 , ~g ∈ C(Ω̄ × R2 , R2 ) and f = (f1 , f2 )T ∈ (C(Ω̄))2 .

2000 Mathematics Subject Classification. 74S05, 76T10.

Key words and phrases. Non-Newtonian fluid; k-Laplacian operator; eigenvalues;

variational method.

c

2012

Texas State University - San Marcos.

Submitted May 17, 2011. Published March 7, 2012.

1

2

O. CHAKRONE, O. DIYER, D. SBIBIH

1

EJDE-2012/37

Γ3

0.5

Γ1 0

Γ2

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

x

−0.5

Γ4

−1

Figure 1. Geometry of channel

For α ∈ R, we consider the nonlinear Stokes problem

∂p

= g1 (x, y, u1 ) + f1 in Ω,

−∆k u1 +

∂x

∂p

−∆k u2 +

= g2 (x, y, u2 ) + f2 in Ω,

∂y

∂u1

∂u2

div u =

+

= 0 in Ω,

∂x

∂y

u1 (0, y) = u1 (1, y) on [−1, 1],

u2 (0, y) = u2 (1, y)

(1.1)

on [−1, 1],

∂u1

∂u1

(0, y) =

(1, y) on [−1, 1],

∂x

∂x

∂u2

∂u2

|∇u2 (0, y)|k−2

(0, y) = |∇u2 (1, y)|k−2

(1, y)

∂x

∂x

p(1, y) − p(0, y) = −αon [−1, 1].

on [−1, 1],

We assume also the growth condition:

|gi (x, y, s)| ≤ c|s|k−1 + d(x, y) ∀(x, y)T ∈ Ω, ∀s ∈ R,

k0

1

k

1

k0

(1.2)

where c ∈ R and d ∈ L (Ω), with + = 1.

Note that the second member of (1.1) depends on u and since the pressure

difference is constant between two parallel plates of the specific domain, we prove

that we can associate to (1.1) an energy functional ψ. So a critical point of ψ is

a solution of (1.1). We denote by V the closure of V in the space (W 1,k (Ω))2 ,

where V = {u = (u1 , u2 )T ∈ (C 1 (Ω̄))2 | div u = 0, ui (0, y) = ui (1, y)on [−1, 1] for

i = 1, 2 and u = 0 on Γ3 ∪ Γ4 }. We want to extend the work done by Amrouche,

Batchi and Batina in the linear case with the Laplacian operator see [1], which

showed equivalence between the classical and variational problem, existence and

uniqueness of the solution in a linear case where f = g = 0. In this paper we

introduce the k-Laplacian operator to describe the movement of non-Newtonian

fluid with a nonlinear second member, the technique used for the resolution is a

EJDE-2012/37

A NON-RESONANCE PROBLEM

3

minimization and is completely different to that given in [1, 2, 6, 9]. In the case

f = 0, g1 (x, y, s1 ) = λ|s1 |k−2 s1 and g2 (x, y, s1 ) = λ|s2 |k−2 s2 , we have established

in [5] that the first eigenfunction

λ1 of (1.1)R is well defined, strictly positive and

R

characterized by λ−1

=

sup{

|u

|k + |u2 |k ; Ω |∇u1 |k + |∇u2 |k = 1, u ∈ V }.

1

1

Ω

This article is organized as follows. In Section 2, we prove that u is a weak

solution of (1.1) if and only if u satisfies a weak formulation independent of pressure

~ k u + ∇p and

p. In Section 3, we introduce the first eigenvalue of the operator −∆

as an application, we prove the existence of solution where the primitive of the

nonlinear function ~g is asymptotically in the left of the first eigenvalue. In Section

4, we add a condition of monotony for the function ~g and we prove the uniqueness

of the solution, then we give an example of such a function ~g which satisfies the

conditions. Finally we give in Section 5 a conclusion.

2. Weak formulation of (1.1)

We establish the equivalence between the classical problem and weak formulation

of problem which is independent of pressure p, This allows us to find the existence

of the weak solution of (1.1) by a new method of minimization.

Definition 2.1. A classical solution of (1.1) is a function (u, p)T ∈ (C 2 (Ω) ∩

C 1 (Ω̄))2 × L2 (Ω) and ∇p ∈ (C(Ω))2 which verify (1.1).

Theorem 2.2. If (u, p)T is a classical solution of (1.1), then

Z 1

Z

Z

2 Z

X

k−2

|∇ui |

∇ui .∇vi − α

v1 (0, y)dy =

~g (x, y, u).v +

f.v

i=1

−1

Ω

Ω

∀v ∈ V

Ω

(2.1)

Proof. If (u, p)T is a classical solution of (1.1) where u = (u1 , u2 )T , then for v =

(v1 , v2 )T ∈ V, we multiply the first equation by v1 , the second equation by v2 of

(1.1) and we integrate on Ω, we obtain

Z

Z

Z

Z

Z

−(∆k u1 )v1 +

−(∆k u2 )v2 + (∇p).v =

~g (x, y, u1 , u2 ).v +

f.v.

Ω

Ω

Ω

Ω

Ω

According to Green’s formula, we have for all 1 ≤ i ≤ 2,

Z

Z

Z

−(∆k ui )vi =

|∇ui |k−2 ∇ui .∇vi −

|∇ui |k−2 ∇ui .~η vi dσ,

Ω

Ω

∂Ω

where ~η is the unit outward normal to ∂Ω. On the one hand, we have

Z

Z

Z

|∇ui |k−2 ∇ui .~η vi dσ =

|∇ui |k−2 ∇ui .~η vi dσ +

|∇ui |k−2 ∇ui .~η vi dσ

∂Ω

Γ1

Γ2

Z

k−2

+

|∇ui |

∇ui .~η vi dσ.

Γ3 ∪Γ4

As v ∈ V,

Z

Γ3 ∪Γ4

T

|∇ui |k−2 ∇ui .~η vi dσ = 0,

we have on Γ1 , ~η = −(1, 0) and on Γ2 , ~η = (1, 0)T , thus

Z

Z 1

∂ui

(0, y)vi (0, y)dy,

|∇ui |k−2 ∇ui .~η vi dσ = −

|∇ui (0, y)|k−2

∂x

Γ1

−1

4

O. CHAKRONE, O. DIYER, D. SBIBIH

EJDE-2012/37

and

Z

k−2

|∇ui |

Z

1

|∇ui (1, y)|k−2

∇ui .~η vi dσ =

−1

Γ2

∂ui

(1, y)vi (1, y)dy.

∂x

As v ∈ V, we have vi (0, y) = vi (1, y), for all −1 ≤ y ≤ 1, i = 1, 2. According to

(1.1), we have

Z

|∇u2 |k−2 ∇u2 .~η v2 = 0.

(2.2)

On the other hand, as

that

∂Ω

∂u1

∂u1

∂y (0, y) = ∂y (1, y),

Z

thus ∇u1 (0, y) = ∇u1 (1, y), we deduce

|∇u1 |k−2 ∇u1 .~η v1 = 0.

∂Ω

Then, by Green’s formula and v ∈ V , we have

Z

Z

Z

∇p.v =

pv.~η −

p div v,

Ω

∂Ω

Ω

and

Z

Z

Z

pv.~η =

∂Ω

pv.~η +

Γ1

Z

pv.~η +

Z

1

=−

p(0, y)v1 (0, y)dy +

−1

Z

pv.~η

Γ3 ∪Γ4

Z 1

Γ2

p(1, y)v1 (1, y)dy

−1

1

(p(1, y) − p(0, y))v1 (0, y)dy

=

−1

Z

1

= −α

v1 (0, y)dy.

−1

This proves (2.1).

Now, we study the reciprocal problem; i.e., if u is a weak solution of (1.1) with

some regularity, then u is a classical solution of (1.1).

Definition 2.3. A weak solution of (1.1) is a function u ∈ V satisfying (2.1).

Theorem 2.4. If u is a weak solution of (1.1) with u ∈ (C 2 (Ω) ∩ C 1 (Ω̄))2 , then

there exists p ∈ L2 (Ω) such that (u, p)T is a classical solution of (1.1). Furthermore

R 1 ∂p

(t, y)dt.

we have ∇p ∈ (C(Ω̄))2 and −α = p(1, y) − p(0, y) = 0 ∂x

Proof. Let u ∈ (C 2 (Ω) ∩ C 1 (Ω̄))2 which satisfies (1.1), by Green’s formula, we have

Z

Z 1

2 Z

X

k−2

~

|∇ui |

∇ui .~η vi dσ −α

v1 (0, y)dy = 0

(−∆k u−~g (x, y, u1 , u2 )−f ).v +

Ω

i=1

∂Ω

−1

(2.3)

for all v ∈ V. We put F = {v ∈ (D(Ω))2 | div v = 0} where D(Ω) is the set of all

infinitely differentiable functions with compact support in Ω. (2.3) becomes

Z

~ k u − ~g (x, y, u1 , u2 ) − f ).v = 0 ∀v ∈ F.

(−∆

Ω

~ k u−~g (x, y, u1 , u2 )−

By (1.2), as u ∈ (C (Ω)∩C 1 (Ω̄))2 and f ∈ (C(Ω̄))2 , we have −∆

2

2

2

f ∈ (C(Ω̄)) ⊂ (L (Ω)) , according to Rham’s theorem see [7, 8], there exists

2

EJDE-2012/37

A NON-RESONANCE PROBLEM

5

~ k u + ∇p = ~g (x, y, u1 , u2 ) + f in (C(Ω̄))2 . Thus

p ∈ L2 (Ω) such that −∆

2 Z

X

i=1

|∇ui |k−2 ∇ui .~η vi dσ − α

Z

1

Z

v1 (0, y)dy =

−1

∂Ω

(∇p).v

∀v ∈ V,

(2.4)

Ω

R 1 ∂p

(t, y)dt ∈ C 1 ([−1, 1]).

where ∇p ∈ (C(Ω̄))2 and y 7→ p(1, y) − p(0, y) = −1 ∂x

∂ui

i

As ui (0, y) = ui (1, y) for all y ∈ [−1, 1], we have ∂u

∂y (0, y) = ∂y (1, y). Moreover

1

2

1

we know that div u = 0 in Ω and u ∈ (C (Ω̄)) , we conclude that ∂u

∂x (0, y) =

∂u2

∂u1

∂u1

∂u2

− ∂y (0, y) = − ∂y (1, y) for all y ∈ [−1, 1]. Thus ∂x (0, y) = ∂x (1, y) and

R

∇u1 (0, y) = ∇u1 (1, y). Hence ∂Ω |∇u1 |k−2 ∇u1 .~η v1 dσ = 0.

On the other hand, according to (2.4), we have

Z

Z 1

Z

k−2

v1 (0, y)dy = (∇p).v ∀v ∈ V

|∇u2 |

∇u2 .~η v2 dσ − α

−1

∂Ω

ZΩ

=

pv.~η

∂Ω

1

Z

(p(1, y) − p(0, y))v1 (0, y)dy.

=

−1

Therefore,

Z

1

−|∇u2 (0, y)|k−2

−1

Z

∂u2

(0, y)v2 (0, y)dy

∂x

1

|∇u2 (1, y)|k−2

+

−1

Z 1

∂u2

(1, y)v2 (1, y)dy − α

∂x

Z

1

v1 (0, y)dy

(2.5)

−1

(p(1, y) − p(0, y))v1 (0, y)dy.

=

−1

1/2

Let H00 (Γ1 ) [1] be the space defined by

1/2

H00 (Γ1 ) = {ϕ ∈ L2 (Γ1 ); ∃v ∈ H 1 (Ω), with v|Γ3 ∪Γ4 = 0, v|Γ1 ∪Γ2 = ϕ}.

(

µ on Γ1 ∪ Γ2

1/2

T

Let µ ∈ H00 (Γ1 ), we put ν = (0, µ2 ) where µ2 =

. It is clear

0 on Γ3 ∪ Γ4 .

R

that ν ∈ (H 1/2 (Γ))2 and ∂Ω ν.~η dσ = 0, so there exists v ∈ (H 1 (Ω))2 such that

div v = 0 in Ω and v = ν on Γ (see [1]); therefore v ∈ V . According to (2.5), we

1/2

have for all µ ∈ H00 (Γ1 ),

Z 1

Z 1

∂u2

k−2 ∂u2

(0, y)µdy =

|∇u2 (1, y)|k−2

(1, y)µdy,

|∇u2 (0, y)|

∂x

∂x

−1

−1

thus

|∇u2 (0, y)|k−2

∂u2

∂u2

(0, y) = |∇u2 (1, y)|k−2

(1, y).

∂x

∂x

According to (2.5), we have

Z 1

Z

−α

v1 (0, y)dy =

−1

1

−1

(p(1, y) − p(0, y))v1 (0, y)dy.

(2.6)

6

O. CHAKRONE, O. DIYER, D. SBIBIH

EJDE-2012/37

1/2

On(the other hand, let γ ∈ H00 (Γ1 ). Now we consider β = (γ1 , 0)T where

R

γ on Γ1 ∪ Γ2

γ1 =

. We have β ∈ (H 1/2 (Γ))2 and ∂Ω β.~η dσ = 0, so there exists

0 on Γ3 ∪ Γ4 .

1

v ∈ (H (Ω))2 such that div v = 0 in Ω and v = β on Γ [1]; therefore, v ∈ V . By (2.6)

R1

R1

−α −1 γdy = −1 (p(1, y)−p(0, y))γdy. Finally we prove p(1, y)−p(0, y) = −α. 3. Existence of a solution

Let us introduce the energy functional associated with (2.1), ψ : V → R:

Z

Z

Z 1

1

1

k

k

|∇u1 | +

|∇u2 | − α

u1 (1, y)dy

ψ(u) =

k

k Ω

−1

Z

Z

Z

Z Ω

−

F1 (x, y, u1 ) −

F2 (x, y, u2 ) −

f1 u1 −

f2 u2 ,

Ω

Ω

Ω

(3.1)

Ω

where

F : Ω × R2 → R; F (x, y, u) = F1 (x, y, u1 ) + F2 (x, y, u2 ) and Fi (x, y, s) =

Rs

g (x, y, t)dt, i = 1, 2. It is clear that ψ is well defined, C 1 on V and for all v ∈ V

0 i

Z 1

Z

Z

2 Z

X

0

k−2

hψ (u), vi =

|∇ui |

∇ui .∇vi − α

v1 (0, y)dy −

~g (x, y, u).v −

f.v.

i=1

−1

Ω

Ω

Ω

(3.2)

We know that a critical point of the function ψ is a weak solution of (1.1) and

reciprocally. We assume that the nonlinearity is asymptotically in the left of the

first eigenvalue of k-Laplacian; i.e.,

λ

(3.3)

F (x, y, s1 , s2 ) ≤ (|s1 |k + |s2 |k ) + ρ(x, y),

k

where ρ ∈ L1 (Ω) and λ < λ1 , λ1 is the first eigenvalue of the problem

∂p

= λ|u1 |k−2 u1 in Ω,

−∆k u1 +

∂x

∂p

−∆k u2 +

= λ|u2 |k−2 u2 in Ω,

∂y

∂u1

∂u2

div u =

+

= 0 in Ω,

∂x

∂y

u1 (0, y) = u1 (1, y) on [−1, 1],

(3.4)

u2 (0, y) = u2 (1, y)

on [−1, 1],

∂u1

∂u1

(0, y) =

(1, y) on [−1, 1],

∂x

∂x

∂u2

∂u2

|∇u2 (0, y)|k−2

(0, y) = |∇u2 (1, y)|k−2

(1, y)

∂x

∂x

p(1, y) − p(0, y) = 0 on [−1, 1].

on [−1, 1],

In [5], we have proved that the first eigenvalue λ1 of (3.4) is well defined, strictly

positive and characterized by

Z

Z

−1

k

k

|∇u1 |k + |∇u2 |k = 1, u ∈ V .

(3.5)

λ1 = sup

|u1 | + |u2 | ;

Ω

So

Z

λ1

Ω

|u1 |k + |u2 |k ≤

Ω

Z

Ω

|∇u1 |k + |∇u2 |k

∀u ∈ V.

(3.6)

EJDE-2012/37

A NON-RESONANCE PROBLEM

7

Theorem 3.1. Assume that (1.2)and(3.3) are satisfied, then there exists u ∈ V

such that ψ(u) = inf v∈V ψ(v). Consequently, u is the weak solution of (1.1).

Proof. As ψ is convex and class C 1 , it suffices to show that ψ is coercive;

R i.e., ψ(u) →

+∞ when kukW 1,k → +∞. According to (3.6), the function u 7→ ( Ω |∇u1 |k )1/k +

R

( Ω |∇u2 |k )1/k := kukV define a norm in V . We have successively

Z 1

Z

Z

Z

1

1

|∇u1 |k +

|∇u2 |k − α

u1 (1, y)dy − F (x, y, u) − hf, ui, (3.7)

ψ(u) =

k Ω

k Ω

−1

Ω

Z

hf, ui =

Z

f2 u2 ≤

f1 u1 +

Ω

Ω

2

X

kfi kLk0 kui kLk

i=1

≤c

2

X

k∇ui k(Lk )2 , where c > 0

i=1

= ckukV .

Z

1

Z

u1 (1, y)dy ≤ |λ|

λ

−1

|u1 (1, y)|dy

∂Ω

Z

≤ |λ|c0 (

|u1 (1, y)|k )1/k dy (Holder’s inequality), where c0 > 0

∂Ω

Z

0

≤ |λ|c ( |∇u1 |k )1/k (V → (Lk (∂Ω))2 trace theorem )

Ω

= c00 kukV ,

where c00 > 0,

1,k

1,k

the trace theorem is because V ⊂ Wdiv

(Ω) and Wdiv

(Ω) → (Lk (∂Ω))2 with continuous injection.

Z

Z

Z

α

|u1 |k + |u2 |k +

ρ(x, y)

F (x, y, u) ≤

k Ω

Ω

Ω

Z

Z

α

e

|∇u1 |k + |∇u2 |k +

ρ(x, y),

≤

λ1 k Ω

Ω

(

0 if α < 0

where α

e :=

It follows that

α if α ≥ 0.

Z

Z

1

α

e

ψ(u) ≥ (1 − )

|∇u1 |k + |∇u2 |k − ckukV − c0 kukV −

ρ(x, y).

k

λ1 Ω

Ω

Hence

Z

1

α

e

ψ(u) ≥ (1 − )kukkV − c00 kukV −

ρ(x, y), where c00 > 0.

(3.8)

k

λ1

Ω

Finally, as (1 −

α

e

λ1 )

> 0, the property is proved.

4. Uniqueness of the solution

We assume again that the function ~g is decreasing in the following sense:

(~g (x, y, ξ) − ~g (x, y, ξ 0 ), ξ − ξ 0 ) ≤ 0

for all ξ, ξ 0 ∈ R2 .

Theorem 4.1. Problem (2.1) has a unique solution.

(4.1)

8

O. CHAKRONE, O. DIYER, D. SBIBIH

EJDE-2012/37

Proof. Let u and u

e be two solutions of problem (2.1). For all v ∈ V , we have

Z

2

o

X

{ [(|∇ui |k−2 ∇ui − |∇e

ui |k−2 ∇e

ui ).∇vi − (gi (x, y, ui ) − gi (x, y, u

ei ))vi ] = 0.

Ω

i=1

(4.2)

In particular for v = u − u

e, we have

Z

2

Xn

[(|∇ui |k−2 ∇ui − |∇e

ui |k−2 ∇e

ui ).∇(ui − ũi )

Ω

i=1

(4.3)

− (gi (x, y, ui ) − gi (x, y, uei ))(ui − ũi )]} = 0.

k−2

As (|ξ|

0 k−2 0

ξ ).(ξ − ξ 0 ) > 0 for all ξ 6= ξ 0 ∈ R2 and (4.1), we deduce that

ξ − |ξ |

2 Z

X

i=1

(|∇ui |k−2 ∇ui − |∇e

ui |k−2 ∇e

ui ).∇(ui − ũi ) = 0.

(4.4)

Ω

Thus ∇ui = ∇ũi , i = 1, 2, therefore ui = u

ei + , where ∈ R. As ui , ũi ∈ V , we

have = 0, this completes the proof.

Example of function ~g . We consider ~g (x, y, s) = (g1 (s1 ), g2 (s2 )) for all s =

(s1 , s2 ) ∈ R2 and (x, y)T ∈ R2 , where

k−1

α si

if si ≥ (k − 1)1/k

2 ( 1+(sk ) )

i

gi (si ) =

k−1

α

k

2k (k − 1)

k−2

(−s

)

s

α( i

i

2 1+(−si )k )

if − (k − 1)1/k ≤ si ≤ (k − 1)1/k

+ αk (k − 1)(k−1)/k

if si ≤ −(k − 1)1/k .

We have gi (x, y, .) is a continuous function, so it has a primitive Fi , for i = 1, 2.

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

Figure 2. Graph of gi

For k = 2 and α = 1, Figure (2), we have

s

1

if s ≥ 1

2 ( 1+s2 )

1

gi (s) = 4

if − 1 ≤ s ≤ 1

1 s

1

if s ≤ 1.

2 ( 1+s2 ) + 2

EJDE-2012/37

A NON-RESONANCE PROBLEM

9

(i) g satisfies (1.2), indeed: If si ≥ (k − 1)1/k , then

|gi (s)| =

α |si |k−1

α

(

) ≤ |si |k−1 .

k

2 1 + (|si | )

2

If si ≤ −(k − 1)1/k , then

|gi (s)| =

α |si |k−1

α

α

(

) + c ≤ |si |k−1 + c ≤ |s|k−1 + c0 for all s ∈ R2 ,

2 1 + (|si |k )

2

2

k−1

α

(k − 1) k .

where c ∈ R and c0 = c + 2k

(ii) We

have

F

(x,

y,

s

,

s

)

=

F

1

2

1 (x, y, s1 ) + F2 (x, y, s2 ), where Fi (x, y, s) =

Rs

g

(x,

y,

t)dt,

i=1,2.

So

i

0

Z s

Z s

α |t|k−2 t

Fi (x, y, s) =

gi (t)dt ≤

(

)dt + c, where c ∈ R.

k

0

0 2 1 + |t|

≤

α

ln(1 + |s|k ) + c0 , where c0 ∈ R.

2k

Thus

α

α

ln(1 + |s1 |k ) +

ln(1 + |s2 |k ) + c0

2k

2k

α

≤

(|s1 |k + |s2 |k ) + c0

2k

k

α

≤ (s21 + s21 ) 2 + c0 ,

k

consequently F satisfies condition (3.3).

(iii) Finally ~g is decreasing. For si ≥ (k − 1)1/k ,

F (x, y, s1 , s2 ) = F1 (x, y, s1 ) + F2 (x, y, s2 ) ≤

gi0 (si ) =

(1 + (si )k ) − sk−1

(ksk−1

)

α (k − 1)sk−2

i

i

i

(

)

2

(1 + (si )k )2

=

α (ksik−2 + ksi2k−2 − sk−2

− s2k−2

− ks2k−2

i

i

i

)

(

2

(1 + (si )k )2

=

α sk−2

(k − 1 − ski )

( i

) ≤ 0.

2

(1 + (si )k )2

For si ≤ −(k − 1)1/k ,

αh

gi0 (s) =

(−(k − 2)(−si )k−3 si + (−si )k−2 )(1 + (−si )k )

2

i

+ (−si )k−2 si (k(−si )k−1 ) /(1 + (−si )k )2

αh

=

− (k − 2)(−si )k−3 si − (k − 2)(−si )2k−3 si + (−si )k−2

2

i

+ (−si )2k−2 + k(−si )2k−3 si /(1 + (−si )k )2

αh

=

− (k − 2)(−si )k−3 si + 2(−si )2k−3 si + (−si )k−2

2

i

+ (−si )2k−2 /(1 + (−si )k )2

α

= (−si )k−3 − (k − 2)si + 2(−si )k si + (−si ) + (−si )k+1 /(1 + (−si )k )2

2

10

O. CHAKRONE, O. DIYER, D. SBIBIH

EJDE-2012/37

α

(−si )k−3 − ksi + si + (−si )k (2si − si ) /(1 + (−si )k )2

2

α

= (−si )k−3 − (k − 1)si + (−si )k si /(1 + (−si )k )2

2

α

= (−si )k−3 si − (k − 1) + (−si )k /(1 + (−si )k )2 ≤ 0.

2

Conclusion. We have shown the existence and uniqueness of a solution by a minimization method. We can also define the other eigenvalues and placed them between

two consecutive eigenvalues, in this case we must consider using saddle points.

=

References

[1] C. Amrouche, M. Batchi, J. Batina; Navier-Stokes equations with periodic boundary conditions

and pressure loss, Applied Mathematics Letters. 20 (2007), 48-53.

[2] C. Amrouche, E. Ouazar, Solutions faibles H 2 pour un modèle de fluide non newtonien, C. R.

Acad. Sci. Paris, Ser. I341 (2005), 387-392.

[3] A. Anane; Simplicité et isolation de la première valeur propre du p-Laplacien avec poids, C.

R. Acad. Sci. Paris, t. 305 (1987), 725-728.

[4] A. Anane, O. Chakrone; Sur un théorème de point critique et application aùn problème de

non-résonance entre deux valeurs propres du p-Laplacien Annales de la faculté des sciences

de Toulouse sér. 6, 9 No. 1 (2000), 5-30.

[5] O. Chakrone, O. Diyer, D. Sbibih; Properties of the first eigenvalue of a model for non Newtonian fluids, Electronic Journal of Dfferential equations. Vol. 2010 (2010), No. 156, 1-8.

[6] J. Cossio, S. Herrón; Existence of radial solutions for an asymptotically linear p-Laplacian

problem; J. Math. Anal. Appl. 345 (2008), 583-592.

[7] R. Dautray, J. L. Lions; Analyse mathématique et calcul numérique pour les sciences et les

techniques, tome 3, Masson, Paris, 1985.

[8] P. Dreyfuss; Introduction à l’analyse des équations de Navier-Stokes; note de cours, 69 pages,

rapport de l’université de Fribourg, 2005, http://www.iecn.u-nancy.fr/∼dreyfuss/P10.pdf.

[9] P. Sváček; On approximation of non-Newtonian fluid flow by the finite element method, Computational and applied Mathematics. 218 (2008), 167-174.

Omar Chakrone

Université Mohammed I, Faculté des sciences, Laboratoire LANOL, Oujda, Maroc

E-mail address: chakrone@yahoo.fr

Okacha Diyer

Université Mohammed I, Ecole Supérieure de Technologie, Laboratoire MATSI, Oujda,

Maroc

E-mail address: odiyer@yahoo.fr

Driss Sbibih

Université Mohammed I, Ecole Supérieure de Technologie, Laboratoire MATSI, Oujda,

Maroc

E-mail address: sbibih@yahoo.fr