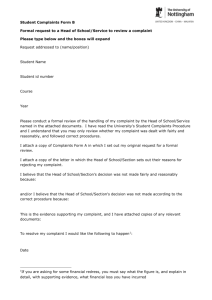

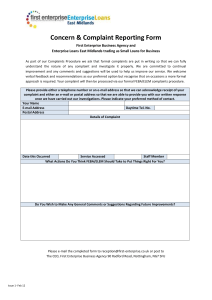

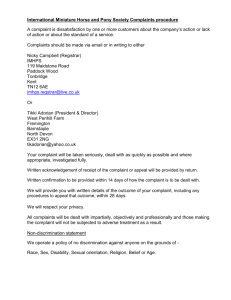

My expectations for raising concerns and complaints

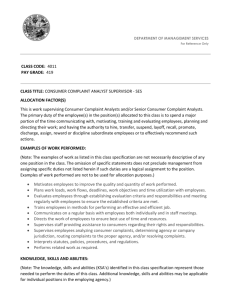

advertisement