MANUFACTURING NEW URBAN

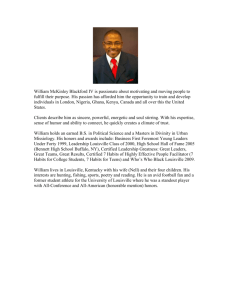

advertisement