GAO U.S. ATLANTIC COMMAND Challenging Role in the

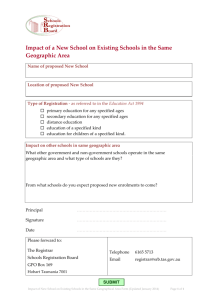

advertisement