U.S. Air and Ground Conventional Forces for NATO: Firepower Issues BACKGROUND PAPER

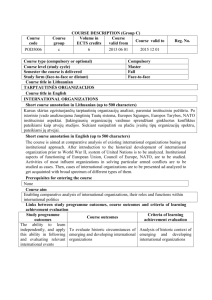

advertisement