Document 10744438

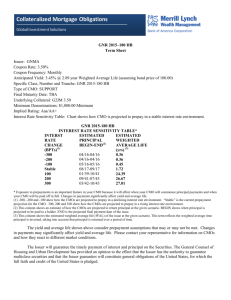

advertisement