Better Get It Right the ... Additionality in the California Carbon Market

advertisement

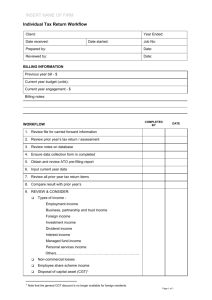

Better Get It Right the First Time: How CARB’s Offset Invalidation Provisions Promote Additionality in the California Carbon Market Jack Lyman I. INTRODUCTION In 2006, the California legislature passed the Global Warming Solutions Act (“AB 32” or “the Act”),1 as a means to address climate change. AB 32 directed the California Air Resources Board (“CARB” or “the Board”) to develop a regulatory scheme to limit greenhouse gas (“GHG”) emissions from the state’s largest polluters. 2 The Act seeks to cap statewide GHG emissions at their 1990 levels by 2020.3 AB 32 contemplated and fully authorized use of market mechanisms to achieve this goal.4 Pursuant to its legislative directive, CARB adopted a cap-and-trade regime for GHG emissions. The program began operation on January 1, 2012, with an enforceable compliance obligation starting on January 1, 2013.5 Power plants and industrial facilities (and, starting in 2015, the transportation and natural gas sectors as well) are now required to account for GHG emissions resulting from their activities by holding allowances or purchasing carbon offsets issued by CARB.6 1 California Global Warming Solutions Act of 2006, Assemb. B. No. 32 (codified at CAL. HEALTH & SAFETY CODE § 38500 et seq. (2006)). 2 See CAL. HEALTH & SAFETY CODE §§ 38570, 38562. 3 See id. § 38550. 4 See Justin Kirk, Note, Creating an Emissions Trading System for Greenhouse Gases: Recommendations to the California Air Resources Board, 26 VA. ENVTL. L. J. 547, 547 (2008). 5 CAP-AND-TRADE PROGRAM, CAL. AIR RESOURCES BD. (Apr. 10, 2013), http://www.arb.ca.gov/cc/capandtrade/capandtrade.htm 6 Daniel De Deo & Marisa Martin Lewandowski, California Carbon Offsets: Here Today, Where Tomorrow? 16 A.B.A. SEC. OF ENVT., ENERGY, AND RESOURCES: CLIMATE CHANGE, SUSTAINABLE DEV., AND ECOSYSTEMS COMM. NEWSL. 12, 12 (Apr. 2013), available at http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publications/nr_newsletters/ccsde/201304_ccsde.authcheckdam.pdf. JBL 1 The California system is unique in its approach to addressing the additionality requirement for offsets, which is a vital component of most environmental markets.7 In addition to more traditional generalized standards, the CARB implementing regulations include provisions allowing CARB to invalidate an offset in certain circumstances at any time within 8 years of issuance in most cases.8 These invalidation provisions are both a novel and appropriate solution to the additionality problem inherent in environmental markets. The risk of invalidation will be reflected in the offset price, fairness concerns can be sufficiently tempered by contract law, and the threat of invalidation for non-additionality will incentivize additionality. II. OFFSETS AND THE PROBLEM OF ADDITIONALITY A common feature in most carbon markets, including California’s, is the availability of offsets that regulated entities may purchase, instead of holding allowances, in order to meet compliance requirements. Carbon offsets are ecosystem payments for activities that sequester or avoid emissions of carbon dioxide or other GHGs.9 Offsets can produce significant economic and environmental benefits for landowners, farmers, ranchers, and foresters who participate in the offsets market through documentation of emissions reductions and generation of marketable credits.10 Offsets also have great potential as inspiration for innovation in these and other sectors 7 See Karen Bennett, Note, Additionality: The Next Step for Ecosystem Services Markets, 20 DUKE ENVTL. L. & POL’Y F. 417, 419 (2010). CARB has released an exhaustive guidance document for the requirements and issuance of offset credits. See CHAPTER 6: WHAT ARE THE REQUIREMENTS FOR OFFSET CREDITS AND HOW ARE THEY ISSUED? (GUIDANCE FOR REGULATION SECTIONS 95970–95990), CAL. AIR RESOURCES BD. (Dec. 19, 2012), available at http://www.arb.ca.gov/cc/capandtrade/offsets/chapter6.pdf. 8 See CAL. CODE REGS. tit. 17, § 95985 (2013). 9 See David Cooley & Lydia Olander, Stacking Ecosystem Services Payments: Risks and Solutions, 42 ENVTL. L. REP. NEWS & ANALYSIS 10150, 10153 (2012). 10 See ENVTL. DEF. FUND, The Role of Offsets in California’s Cap-and-Trade Regulation: Frequently Asked Questions (April 2012), http://www.edf.org/sites/default/files/OffsetsPercentagesFAQFinal%20041612.pdf. JBL 2 of the economy that contribute to GHG emissions but currently lack the necessary emissions measurement systems for inclusion in the program.11 For the California market, CARB has authorized four general categories of offsets: (1) Ozone Depleting Substance Projects, (2) Livestock Projects, (3) Urban Forest Projects, and (4) U.S. Forest Projects.12 The offset project also must be located in Mexico, Canada, or the United States, in addition to other requirements. 13 Regulated entities in California may use CARBissued offset credits to meet up to eight percent of their triennial compliance obligations under the market regulations. 14 Each offset credit is equal to one metric ton of carbon dioxide equivalent, and the offset’s carbon reduction or removal must be “real, additional, quantifiable, permanent, verifiable, and enforceable.”15 Finally, the regulations require third-party verification of all carbon offsets before the corresponding credits may be issued.16 One of the requirements of California’s (and other) offset program is that the offset must be “additional.”17 The CARB regulations define additional, in the context of offset credits, as 11 See id. CAL. CODE REGS. tit. 17, § 95973(a)(2)(C). As demand for offsets increases, CARB will probably allow for other offset protocols. See William Sloan et al., Court Rejects Challenge to California’s Cap-and-Trade Carbon Offset Program, MORRISON FOERSTER (Jan. 20, 2013), http://www.mofo.com/files/Uploads/Images/130130-Cap-andTrade-Offset.pdf; ENVTL. DEF. FUND, supra note 10. In March 2013, California began consideration of two new offset categories based on reducing methane emissions from coal mines and rice fields. See Debra Kahn, California adds more offsets to ease cap-and-trade supply crunch, CLIMATEWIRE, May 2, 2013. If these categories are approved, farmers and mine owners would be able to sell offset credits for improved management of their properties, including draining methane from mines and draining water from rice fields to stop old plants from releasing methane during decomposition. See id. 13 CAL. CODE REGS. tit. 17, § 95973(a)(3). 14 See COMPLIANCE OFFSET PROGRAM, CAL. AIR RESOURCES BD. (May 1, 2013), http://www.arb.ca.gov/cc/capandtrade/offsets/offsets.htm. Regulators typically limit the amount of compliance obligations that can be met through offsets, so that actual emissions reductions will be achieved. See Victor B. Flatt, “Offsetting” Crisis?—Climate Change Cap-and-Trade Need Not Contribute to Another Financial Meltdown, 39 PEPP. L. REV. 619, 634 (2012). 15 CAL. CODE REGS. tit. 17, § 95802(a)(12). 16 Id. § 95977(a). 17 See id. § 95802(a)(12). Most carbon markets explicitly identify additionality as a critical component of the program. See Bennett, supra note 7, at 420–21. 12 JBL 3 “greenhouse gas emission reductions or removals that exceed any greenhouse gas reduction or removals otherwise required by law, regulation or legally binding mandate, and that exceed any greenhouse gas reductions or removals that would otherwise occur in a conservative business-asusual scenario.” 18 This definition is typical of most ecosystem services markets—“to be additional, pollutant reductions or land-use changes must be made or avoided in direct response to payment.”19 The additionality requirement is linked to two related objectives of environmental markets. First, additionality ensures that offsets are a genuine and added enhancement to ecosystem services that compensate for the allowed environmental impact. 20 Second, additionality increases the cost-effectiveness of programs generally; if programs fund only activities that would not have occurred absent the funding (i.e., are “additional”), they save money, which can then be reallocated for other environmental enhancements.21 A simple example is illustrative of additionality and its associated problems in a carbon offset market. A landowner offers to donate a conservation easement, the terms of which expressly prohibit timber harvests and development. This project would almost certainly be eligible as an offset in the California market, as long as it is additional.22 If the landowner would not have conveyed the easement “but for” payment from a regulated entity as an offset, it is 18 CAL. CODE REGS. tit. 17, § 95802(a)(4). The Act defines “business-as-usual scenario” as “the set of conditions reasonably expected to occur within the offset project boundary in the absence of the financial incentives provided by offset credits, taking into account all current laws and regulations, as well as current economic and technological trends.” Id. § 95802(a)(34). The Act defines “conservative” in this context as “utilizing project baseline assumptions, emission factors, and methodologies that are more likely than not to understate net GHG reductions or GHG removal enhancements for an offset project to address uncertainties affecting the calculation or measurement of GHG reductions or GHG removal enhancements.” Id. § 95802(58). 19 Bennett, supra note 7, at 420; see also Cooley & Olander, supra note 9, at 10158 (“The purpose [of additionality] is to ensure that carbon offsets are generated only from activities that would not have occurred in the absence of a payment.”). 20 See Cooley & Olander, supra note 9, at 10158. 21 See id. 22 See CAL. AIR RESOURCES BD., COMPLIANCE OFFSET PROTOCOL: U.S. FOREST PROJECTS 12–24 (Oct. 20, 2011), available at http://www.arb.ca.gov/regact/2010/capandtrade10/copusforest.pdf. JBL 4 additional. If, however, the offset payment was not the impetus for the landowner’s behavior— that is, he would have conveyed the easement anyway for aesthetic reasons or as a tax deduction—the activity is not additional and would not qualify as an offset. III. TRADITIONAL SOLUTIONS TO THE ADDITIONALITY PROBLEM Assessing and monitoring additionality in carbon offset markets is a difficult endeavor. Commentators have identified four approaches (besides California’s) that environmental markets have employed to ensure that services receiving payments as offsets are in fact additional. Each has advantages and disadvantages, and there is some overlap and common ground between each system and California’s approach as well. First is the project-specific assessment model, exemplified by the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism.23 Under this approach, an offset project developer submits a proposal to the regulating entity, which reviews and evaluates whether the project is additional.24 While programs typically have recognized parameters for project evaluation, the decision remains a somewhat subjective one.25 Theoretically, project-specific assessments should render the most accurate determination of additionality, since they are flexible and can more closely analyze 23 See generally U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, Report of the Conference of the Parties on its Seventh Session, Marrakesh Oct. 29-Nov. 10, 2001, U.N. Doc. FCCC/CP/2001/13/Add.2 (Jan. 21, 2002) (describing CDM modalities and procedures), available at http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/cop7/13a02.pdf. For CDM, a project cannot be considered additional by meeting objective criteria alone. See generally U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change, Tool for the Demonstration and Assessment of Additionality, Version 05.2, available at http://cdm.unfccc.int/methodologies/PAmethodologies/tools/am-tool-01-v5.2.pdf (describing objective and subjective requirements considered in the CDM project approval process). 24 See Bennett, supra note 7, at 425. 25 See id. JBL 5 individual intent. 26 However, this blessing is also a curse—the approach is time-consuming, costly, and characterized by some degree of unpredictability.27 Second, many carbon markets are trending towards standardized criteria for additionality assessments, largely in response to the issues presented by the project-specific approach. Under this approach, regulators develop general criteria around observations of typical characteristics for additional projects, which are then translated into objective, pre-determined criteria that sort projects based on the likelihood of additionality.28 Then, projects that meet a minimum specified standard are deemed additional and eligible to participate in the offset market.29 Common criteria include (1) legal/regulatory,30 (2) date,31 (3) performance standard,32 (4) financial,33 (5), common practice,34 (6) technology,35 and (7) size.36 Standardization can be time- and resource-intensive to set up initially, and is possibly more susceptible to fraud and over- and under-inclusion, given its detachment from individual applicants.37 However, once the assessment criteria are established, 26 See id. at 426. See id. at 427. For example, a 2008 study reported that CDM credits are being issued at a rate that is only 2.5 to 5 percent of what is needed. See Michael W. Wara & David G. Victor, A Realistic Policy on International Carbon Offsets 14 (Stanford Univ. Program on Energy and Sustainable Dev., Working Paper No. 74, 2008). 28 See Bennett, supra note 7, at 428. 29 See id. 30 Under this criterion, projects that are already mandated by law are excluded. See id. 31 This criterion excludes projects based on their date of initiation. See id. at 429; Cooley & Olander, supra note 9, at 10159. 32 This criterion requires projects to achieve pollutant or emissions levels better than a previously defined benchmark. See Bennett, supra note 7, at 429. 33 This criterion is the most intuitive but also the most difficult to measure. The assessor searches for evidence that the project could not be implemented without funding as an offset credit. See id. at 429–30; Cooley & Olander, supra note 9, at 10159. 34 Under this criterion, the applicant must show that the proposed activity is uncommon for the region. See Bennett, supra note 7, at 430; Cooley & Olander, supra note 9, at 10159. 35 Here, the project evaluator develops a list of new technologies that are not business-as-usual, use of which are then factored in positively to the additionality assessment. See Bennett, supra note 7, at 430. 36 This criterion excludes projects that are either above or below a specified size. See id. 37 See id. at 431. 27 JBL 6 administrative and transaction costs decrease significantly, and project developers enjoy more certainty in predicting the outcome of their applications.38 CARB has developed standards for determining additionality for each of the four offset protocols in its market.39 These standards were recently upheld by the San Francisco Superior Court in Citizens Climate Lobby v. California Air Resources Board. 40 The petitioners, two citizens groups, challenged the offset standards, claiming that the Act did not authorize CARB to ascertain additionality based on generalized standards. 41 The petitioners argued instead for a project-specific determination to additionality. 42 Deferring to CARB, the court held that the Board reasonably could use a standardized approach to minimize administrative burden.43 A third approach to ensuring additionality in environmental service markets that may be applied in carbon offset markets is use of discounting or trading ratios. Under this method, the regulator sets a trading ratio that discounts the amount of ecosystem services that an offset provider is credited. 44 Given the uncertainty inherent in ecosystem services, the regulator “hedges its bets” by using conservative estimates of carbon reduction or removal, which in turn secures the environmental and economic integrity of the market. 45 For example, a mature 38 See id. at 432. This might be a situation where higher short-term costs are recovered more effectively in the long run. See Robert B. McKinstry, Jr., Putting the Market to Work for Conservation: The Evolving Use of Market-Based Mechanisms to Achieve Environmental Improvement in and Across Multiple Media, 14 PENN. ST. ENVTL. L. REV. 151, 163 (2006). 39 For a thorough discussion of the standards, which is beyond the scope of this paper, see Citizens Climate Lobby v. Cal. Air Resources Bd., No. CGC-12-519554, slip op. at 12–17 (Cal. Super. Ct. 2013), available at http://www.scribd.com/doc/122645121/Citizens-Climate-Lobby-et-al-vs-California-Air-Resources-Board. 40 Citizens Climate Lobby v. Cal. Air Resources Bd., No. CGC-12-519554, slip op. (Cal. Super. Ct. 2013), available at http://www.scribd.com/doc/122645121/Citizens-Climate-Lobby-et-al-vs-California-Air-Resources-Board. 41 See id. at 3. 42 See id. 43 See id. at 33–34. For a thoughtful and concise analysis of the opinion, see Sloan et al., supra note 12, at 1–2. 44 See Bennett, supra note 7, at 432. 45 Cf. McKinstry, supra note 38, at 159–60 (discussing the difficulties of markets in accurately quantifying ecosystem services). JBL 7 deciduous forest would sequester approximately fifteen tons of carbon dioxide per acre. 46 As an offset, and assuming other requirements are met,47 the regulator might credit the landowner with twelve tons of carbon dioxide sequestered per acre as a margin of error. Discounting serves the environmental integrity of the market by building in a safety valve. Discounting is not without costs, however—if the discount rate is too extreme, interested landowners may be deterred from entering the market. 48 Also, projects that truly are additional must bear some of the loss of projects that turn out not to be additional, which raises fairness issues.49 A final approach to additionality that has been suggested elsewhere, and one that is specific to forest offsets, is based on a payment for environmental services system implemented in Mexico. The program uses an econometric system to assess risk of deforestation for lands proposed for inclusion in an offset program. 50 While the program is currently being used to prioritize program applicants, it could easily be converted into an additionality test by establishing a cutoff limit.51 Thus, for example, the program would exclude potential participants whose land exhibited less than an eighty percent chance of deforestation, on the assumption that the somewhat arbitrary cutoff is a reasonable representation of additionality. 52 While data 46 See C. Claiborne Ray, Tree Power, N.Y. TIMES, Dec. 4, 2012, at D2, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/04/science/how-many-pounds-of-carbon-dioxide-does-our-forest-absorb.html. For a more thorough discussion of carbon sequestration and forestry, see Peter L. Gray & Geraldine E. Edens, Carbon Accounting: A Practical Guide for Lawyers, 22 Natural Res. & Envt. 41, 43–49 (2008). 47 Particularly, the landowner would probably have to show that, but for the offset credit, the value of the land would be higher if it were subdivided and developed. 48 See LYDIA OLANDER, DESIGNING OFFSETS POLICY FOR THE U.S. 40 (NICHOLAS INST. 2008), available at http://www.nicholas.duke.edu/ccpp/ccpp_pdfs/offsetspolicy.pdf. 49 See id. 50 See Carlos Muñoz-Piña et al., Paying for the Hydrological Services of Mexico's Forests: Analysis, Negotiations and Results, 65 ECOLOGICAL ECON. 725, 731 (2008). 51 See Bennett, supra note 7, at 435. 52 See id. JBL 8 collection for the inputs to the econometrics model would be expensive and take time, the system does produce quantifiable outputs that may be more favored by policymakers.53 The preceding discussion outlined four approaches to ensuring additionality for offsets in carbon markets. The project-specific and standardization models are the most common, and some also make use of discounting ratios as well. The econometric approach, similar to discounts, when tailored to address additionality, may gain favor as data collection costs decrease. The California approach, on the other hand, injects a novel variable into the equation— threat of invalidation. THE CALIFORNIA APPROACH—INVALIDATION OF NON-ADDITIONAL OFFSETS IV. In its implementing regulations for AB 32, CARB has given itself authority to invalidate offsets in certain circumstances. This includes the power to invalidate offset credits regardless of their location in the market, even credits that have already been surrendered to CARB for compliance purposes.54 Invalidated credits immediately deprive their owner of the credit value, and, in some cases, their loss requires parties that have turned in credits to replace them. 55 In most instances, the burden of invalidation falls on the holder or end-user of the offsets.56 These invalidation provisions are unique, and were probably the result of a political compromise after a stakeholder comment period.57 CARB recognized the value of offsets in mitigating compliance costs and encouraging GHG emissions reductions external to the regulated entities, and 53 See id. This might also be an instance where higher short-term costs are recovered more effectively in the long run. See McKinstry, supra note 38, at 163. 54 See CAL. CODE REGS. tit. 17, § 95895(g), (i). 55 See id. 56 See De Deo & Lewandowski, supra note 6, at 12. 57 See id. JBL 9 simultaneously acknowledged that allowing offsets further delays transition to renewable energy sources.58 Invalidation is authorized in three situations. First, CARB may invalidate an offset credit if “[t]he Offset Data Report contains errors that overstate the amount of GHG reductions or GHG removal enhancements by more than five percent.”59 In other words, the Board issued the project more credits than the project actually realized due to an overstatement in the reporting documents. 60 This may be considered an indirect proxy for additionality, since without the project developer’s generous estimate, the project might not have come to fruition. Second, invalidation is proper where “[t]he offset project activity and implementation of the offset was not in accordance with all local, state, or national environmental and health and safety regulations during the Reporting Period for which the [CARB] offset credit was issued.” 61 Finally, CARB may invalidate upon a determination “that offset credits have been issued in any other voluntary or mandatory program within the same offset project boundary and for the same Reporting Period in which ARB offset credits were issued for GHG reductions and GHG removal enhancements.” 62 This third condition directly invalidates offsets that were not additional, since the credits were issued after the project had already been used for offset credit in another program.63 58 See id.; Flatt, supra note 14, at 637–38. CAL. CODE REGS. tit. 17, § 95895(c)(1). 60 See De Deo & Lewandowski, supra note 6, at 12. For the requirements of the Offset Project Data Report, see CAL. CODE REGS. tit. 17, § 95976(d). 61 CAL. CODE REGS. tit. 17, § 95895(c)(2). 62 Id. § 95895(c)(3). 63 This third invalidation condition also implicates the issue of “stacking” in environmental services markets, which is beyond the scope of this paper. For an excellent discussion and analysis of stacking, see generally Cooley & Olander, supra note 9 (describing stacking, including its benefits and concerns). 59 JBL 10 CARB may invalidate most offset credits anytime within eight years of issuance.64 If the Board makes an initial determination that one of the grounds for invalidation has occurred, it must notify the holder of the credits, the offset project developer, and, in the event the credits have been surrendered, the party that submitted the credits for retirement.65 The notified parties may then submit additional information before CARB makes its final determination. 66 Upon review of the supplemental documents, the Board then has thirty days to make a final decision on whether to invalidate the credits at issue.67 If CARB invalidates an offset credit because a credit was already issued under another program, or because of a violation of environmental, health, or safety laws, it must remove all CARB-issued credits that were issued pursuant to the relevant verification report. 68 Where these invalidated credits have not yet been retired, the credit holders lose only the value of the credits. 69 In contrast, invalidated offsets that have already been surrendered for purposes of compliance must be replaced. 70 If, on the other hand, the invalidation was due to an overstatement in submitted project documents, only the overstated amount will be invalidated,71 64 See CAL. CODE REGS. tit. 17, § 95895(b)(1). If certain specific requirements are met, invalidation is only authorized within three years of issuance. See id. § 95895(b)(1)(A), (B). 65 See id. § 95895(e). 66 See id. § 95895(f). 67 See id. § 95895(f)(4). 68 See id. § 95895(g)(1)(B). 69 See id. § 95895(g)(1)(B). 70 See id. § 95895(h), (i). For non-sequestration projects, the party who submitted the invalidated offset credits for retirement has primary responsibility for their replacement. See id. § 95895(h)(1)(A), (h)(2)(A). For sequestration (i.e. forest) projects, the forest owner who initially sold the invalidated credits is liable for their replacement. See id. § 95985(i)(1)(A), (2)(A). If the responsible party does not replace the invalidated offsets within six months as required, CARB may fine the party $1000 for each non-replaced credit every 45 days after the initial violation (in addition to the party’s replacement obligation). See id. §§ 95895(h)(1)(C), (h)(2)(B), (i)(1)(C), 96014(b), 96013; De Deo & Lewandowski, supra note 6, at 13. 71 See CAL. CODE REGS. tit. 17, § 95895(g)(1)(A). JBL 11 and liability for the invalidated amount will be divided pro rata among the parties who were initially notified of the potential for invalidation.72 V. DISCUSSION: AN EVALUATION OF THE INVALIDATION PROVISIONS AND THEIR PROBABLE CONSEQUENCES A. Uncertainty Is Not Necessarily Bad for the Market At first glance, it appears that CARB’s invalidation provisions will be detrimental to the market for offset credits and the California carbon trading market generally. Regulatory certainty is important for the health and robustness of the market.73 When an offset credit is linked to the underlying performance of the offset project, a significant risk of market nonperformance is created. 74 Additionally, when the regulations create potential for invalidation, the market’s integrity is undermined, and the offset is at risk of becoming “toxic” and threatening the entire market. 75 Thus, investors may be deterred from participating in markets where the regulator retains the ability to unilaterally revoke a previously-issued credit for non-performance of the underlying asset, since they could lose their investment at any time in the eight years following the credit’s issuance. This shroud of uncertainty does not doom the offset credit market, however. Markets excel at absorbing uncertainty into the price of the commodity. The risk of offset nonperformance or underperformance can easily be reflected in the price. Since CARB only invalidates the portion of the offset credit that was overstated at its issuance, the market can 72 See id. § 95895(h)(1). Cf. Ann Powers, Reducing Nitrogen Pollution on Long Island Sound: Is There a Place for Pollutant Trading?, 23 COLUM. J. ENVTL. L. 137, 178 n.211 (1998) (noting that participants in an effluent trading market “suggest[ed] that some minimum time period be established during which the discharge limitation subject to trading will not be changed, in order to foster market certainty”). 74 See Flatt, supra note 14, at 635. 75 See id. at 635, 637. 73 JBL 12 understand this signal.76 Since purchasers enter the market aware that the good may lose some or all of its value in the near future, they will demand a discount for taking on this risk. Thus, the price for offset credits will decrease, and purchasers can hold these savings for when invalidation inevitably occurs and the underlying offsets need to be replaced. B. Fairness Implications and Contract Remedies The invalidation provisions also implicate fairness notions for the marketplace. Given the active trading in the market77 and the eight-year period within which CARB reserves the right to invalidate an offset,78 the credits will be widely dispersed at any given time. Some may still remain with the project developer, some may be held by a regulated entity, and some may have already been retired. But, regardless of where the credits are in the market, the party that ultimately retires the credits with CARB is on the hook if they are invalidated. 79 The affected party may have had no role in creating or may be totally unaware of the condition that caused the invalidation, or may be several parties removed from the offset development where the cause for invalidation likely arose.80 Despite these unfairness concerns, contract law and careful drafting should provide an adequate solution. Though the likelihood of invalidation is slight, the cost of invalidation is severe, and parties to each offset credit negotiation and transaction should make informed accommodation for the party that would bear the loss in the case of invalidation. In the absence 76 See id. at 635–36. The American Carbon Registry, one of CARB’s approved offset registries, reports that 37,516,575 Emission Reduction Tons have been issued, 2,905,184 have been retired, and 8,906,112 have been traded. CARBON REGISTRY, AM. CARBON REGISTRY, http://americancarbonregistry.org/carbon-registry (last visited 5/2/13). The Client Action Reserve, CARB’s other approved offset registry, reports that 34,001,638 Climate Reserve Tons have been issued. CLIMATE ACTION RES., http://www.climateactionreserve.org/ (last visited 5/2/13). 78 See supra note 59 and accompanying text. 79 See supra notes 63–67 and accompanying text. 80 See De Deo & Lewandowski, supra note 6, at 13. 77 JBL 13 of clear and careful drafting, breach of contract actions will be the prime recourse for subsequent parties who purchased offset credits that were later invalidated through no fault of their own.81 Proper due diligence of counterparties and offset projects, as well as creditworthiness, will also be crucial for purchasers of offset credits.82 C. The Threat of Invalidation for Non-Additionality Will Ensure Additionality The CARB invalidation provisions are an innovative means to promote additionality in its market for carbon offsets. Before even entering the market, offset project developers are “on notice” that they had better get the offset right the first time. That means not overstating the carbon reduction or removal value of the offset during the application process, and not attempting to “stack” the credits by reaping benefits from both CARB and another offset market. This is provided, of course, that project developers have proper incentives to begin with—some or all of the liability for an invalidated offset must fall on them. As the regulations are currently structured,83 that means that arm’s-length negotiations and full information between the parties are of utmost importance. The invalidation provisions can work in tandem with the previously discussed standards for CARB’s offset protocols. 84 The generalized standards perform as a threshold test for additionality. The threat of invalidation then functions as a secondary safeguard, in two ways. First, for the sanctity of the market, it adds financial incentives for project developers to not cut corners at the start of the process. Second, it serves the environmental integrity of the market by keeping out non-additional offsets from the start and ensuring replacement of non-additional 81 See id. See id. 83 See supra notes 68–72 and accompanying text. 84 See supra notes 39–43 and accompanying text. 82 JBL 14 offsets later. Thus, while unprecedented, the invalidation provisions in the CARB regulations function as a powerful incentive for additionality, especially when coupled with the initial generalized standards. VI. CONCLUSION CARB’s invalidation provisions for offset credits in the California carbon market represent an innovative approach to addressing the problem of additionality. The provisions allow the Board to invalidate an offset credit if any one of three criteria is met, including circumstances where the project developer overstated the carbon reduction or sequestration value of the offset, and where the offset project had already received credit as an offset from another source. Whether directly or indirectly, these provisions help ensure additionality, and their importance to the market is not discounted by uncertainty or fairness concerns. The market can easily adjust for regulatory uncertainty by accommodating the threat of invalidation into the price for offset credits, and contract law should provide sufficient fairness protections for market participants. The California carbon market already provides a model for other carbon markets, and subsequent imitators should be sure to include invalidation provisions as well. JBL 15