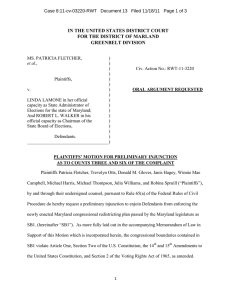

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MARLAND

advertisement