- i -

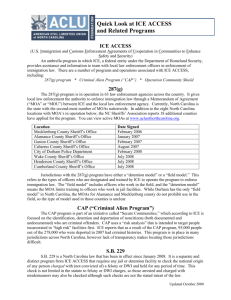

advertisement