CHAPTER 1 SUPPLYING THE THEATER OF OPERATIONS Section I PRE-WAR SUPPLY SUPPORT

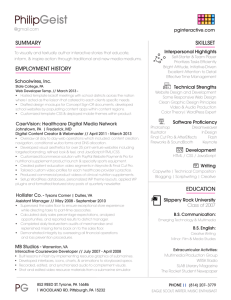

advertisement