LiveScience.com, NY 02-22-07 Chimps Make Spears and Hunt Bushbabies

advertisement

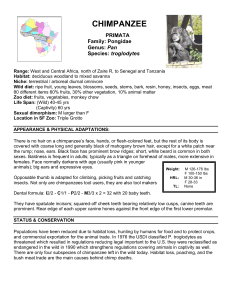

LiveScience.com, NY 02-22-07 Chimps Make Spears and Hunt Bushbabies By Charles Q. Choi Special to LiveScience Chimpanzees are capable of making spears to hunt other primates and have been seen using the weapons to apparently kill bushbabies for meat, scientists announced today. The researchers based their findings on observations of omnivorous chimps [image] that dwell in savannahs similar to those from which humanity's ancestors are thought to have emerged. "It is not adult males, but young chimpanzees, including adolescent females, who are exhibiting this behavior," Jill Pruetz, a primatologist at Iowa State University, told LiveScience. Bushbabies are nocturnal primates that range from the size of chipmunks to opossums, They sleep inside hollow branches or tree trunks during the day and are known for their leaping ability, not to mention being really cute. Image: David Haring via Duke University "This has important implications for how we think about the evolution of tool use in our own species," Pruetz added. "We have tended to emphasize the role of adult males in hunting, and this research supports the assertion that we should not ignore females and other individuals." Earlier this month, scientists reported that chimpanzees used stone tools as early as 4,300 years ago, suggesting that they learned to make and use the tools on their own, rather than copying humans. An unexpected finding The scientists investigated the Fongoli community of savannah-dwelling chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) [image] in southeastern Senegal. The researchers saw 10 different chimps fashioning spear-like tools to forcibly jab at nocturnal primates known as lesser bushbabies (Galago senegalensis), which sleep inside hollow branches or tree trunks during the day. After their attacks, the chimps sniffed or licked their weapons, as if to see whether or not they shed blood. "I was flabbergasted," Pruetz said. Previously, researchers had spotted one chimpanzee using tools to flush out mammalian prey, specifically employing a branch to rouse a squirrel. However, Pruetz and her colleague, Cambridge biological anthropologist Paco Bertolani, saw something far more complex. The chimps routinely broke off branches, trimmed them of twigs, leaves and bark and sharpened the tips of their spears with their teeth. There was just one successful attempt in 22 recorded instances of the chimpanzee hunts with their spears. "Still, this involves significantly less energy than in chasing down monkeys, so it is not surprising that it evolved," Pruetz said. More Monkey Business The red colobus monkeys that are the chimp's favored prey are absent in the relatively dry savannahs where the chimps live, as is much prey, Pruetz said. This may have spurred efforts to catch meat by other means. Females and juveniles may especially be drawn to hunting "perhaps to exploit niches that adult males haven't, using innovation and creativity to get around competition," Pruetz said. Intense field work It took four years for the chimpanzees [image] to become comfortable enough with the scientists to allow them to follow the chimps around and observe behaviors such as hunting. "The greatest difficulty initially was finding them," Pruetz recalled. Unlike chimpanzees that dwell in tropical forests, whose home ranges are usually just roughly four square miles large, savannah-dwelling chimpanzee home ranges are 25 square miles in size or more. "Nowadays, we basically stay with them all day until they go to sleep, and we come back before they wake up, to never let them out of our sight," Pruetz said. "It can take 30 minutes to two hours to walk back to camp after they go to sleep around 6 or 7 p.m., and we have to be back when they wake up around 6 a.m., so it can be exhausting. We're looking into getting a motorcycle." Perhaps the greatest obstacle to the research, Pruetz said, is the growing human population in the area, "which threatens to disturb the chimpanzees' habitat and may eventually result in either forcing them from the area or into extinction." Pruetz and Bertolani detailed their findings online Feb. 22 in the journal Current Biology.