Associated Press 10-09-06 Green is a hard sell

advertisement

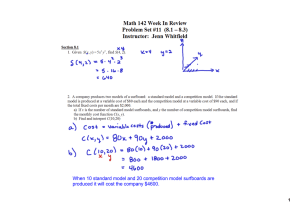

Associated Press 10-09-06 Green is a hard sell Alternative technology has yet to be promoted to a high priority for most people By STEPHANIE HOO The Associated Press Solar panels were perfected decades ago. Turning corn into fuel uses the most basic science. As for wind power, windmills have been around for more than a thousand years. AP photo Today's wind turbines are adapted from aerospace and are used to generate electricity. Like with solar, they suffer from a perception problem. Yet, we're still burning gas and coal and obliterating forests. Why the long delays in getting alternative technology to the market? The reasons are a brew of cost, perception and politics. Consider the evidence: Building Materials Architects can now design houses made of everything from recycled plastic to compressed sawdust, yet most are still made by chopping down trees for timber. New York-based architect Michael McDonough, for one, is a proponent of "structural insulated panels," which marry an inner core of insulating foam with an outer shell made of anything from concrete to a paste-free mix of sawdust and water. "Imagine a piece of wood that comes with insulation, that works perfectly with the most advanced heating and cooling systems," he says. And, the technology has been around since the 1930s, he says. "It was invented by the U.S. Forestry Service as a way to save wood." Yet, 70 years later, the panels still haven't caught on -- even though they are widely available, are more durable than wood, and cost about the same as wood but with 300 percent more energy efficiency, McDonough says. The delay "is simply resistance based on habit, nothing else," he says. Solar Panels Solar panels are billed as a way to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels, which are nonrenewable and cause pollution. More and more homes have solar panels. But most still do not. Homeowners can save thousands of dollars in energy costs over time if they install them, but builders may balk at the upfront costs. The price tag for an array of solar panels to power an individual home is about $20,000 -- though many states offer rebates to cover a large portion of the cost, as much as 70 percent. Architect Michael McDonough promotes alternative building materials while at the NextFest technology fair. Still, "a home builder is not likely to put a system on if he's building on spec," says Joe Laquatra, a professor of design and environmental analysis at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. "Home builders trust technology they're used to. They operate in a very competitive environment." Part of solar's challenge is overcoming a bad reputation. Early solar panels unveiled in the late '70s and early '80s suffered engineering problems, but those problems have been resolved, he says. Still, energy efficiency just isn't a priority for many consumers, he adds. "What are some of the trends we see in home building? The home theaters, higher ceilings, nice kitchens. And people still look at home costs as PITI -principle, interest, taxes, insurance," he says. "I tell people to put an 'e' at the end of that, too -- think about energy costs." Wind Power Windmills date to 7th-century Persia, according to the Encyclopedia Britannica. By the 12th century, they had spread to China and across Europe, as mankind harnessed the wind for power. Today's wind turbines are adapted from aerospace and are used to generate electricity. Like with solar, they suffer from a perception problem -- as well as resistance from town zoning boards, Laquatra says. "People have the misconception that they're noisy," he says, but "you stand next to one and you can barely hear anything." Also, wind turbines are expensive because they aren't mass produced. To power up an individual home with wind would cost about $50,000, McDonough says. Again, many states offer deep rebates, but the price tag would ideally fall if production is ramped up, he says. Meanwhile, commercial wind farms have faced resistance when trying to sell their power to utility companies, says David Osterberg, director of the University of Iowa's Environmental Health Sciences Research Center. "That's one of the problems with renewable energy; it's not the technology but who is going to buy it." Ethanol Biofuels like corn-based ethanol are touted as the future of energy. In reality, ethanol is made using the most basic science imaginable -- corn is crushed and then turned into alcohol. The delay in it becoming more widespread is, very simply, "the stranglehold of Big Oil," Osterberg says. "Part of it is a policy that has been so biased toward gas and oil that we've been allowed to get in a very vulnerable position," he says, citing U.S. dependence on imported oil. That said, corn alone isn't going to save us, says David Swenson, an economist at Iowa State University. Unlike Osterberg, he is less than bullish on corn. Not only is there is a limit to how much corn the U.S. can produce, but growing corn requires a lot of energy and chemicals, and the U.S. ethanol industry is protected by huge subsidies and curbs on imports from places like Brazil. "We're moving away from corn now to something else, which is any kind of cellulose" such as field grass, rice hulls, peanut hulls and even unused corn stalks, Swenson says. Scientists are still working on breaking down those materials, but "we don't have anywhere near the public resources devoted to developing alternative resources," he says.