The Wall Street Journal 10-03-06

advertisement

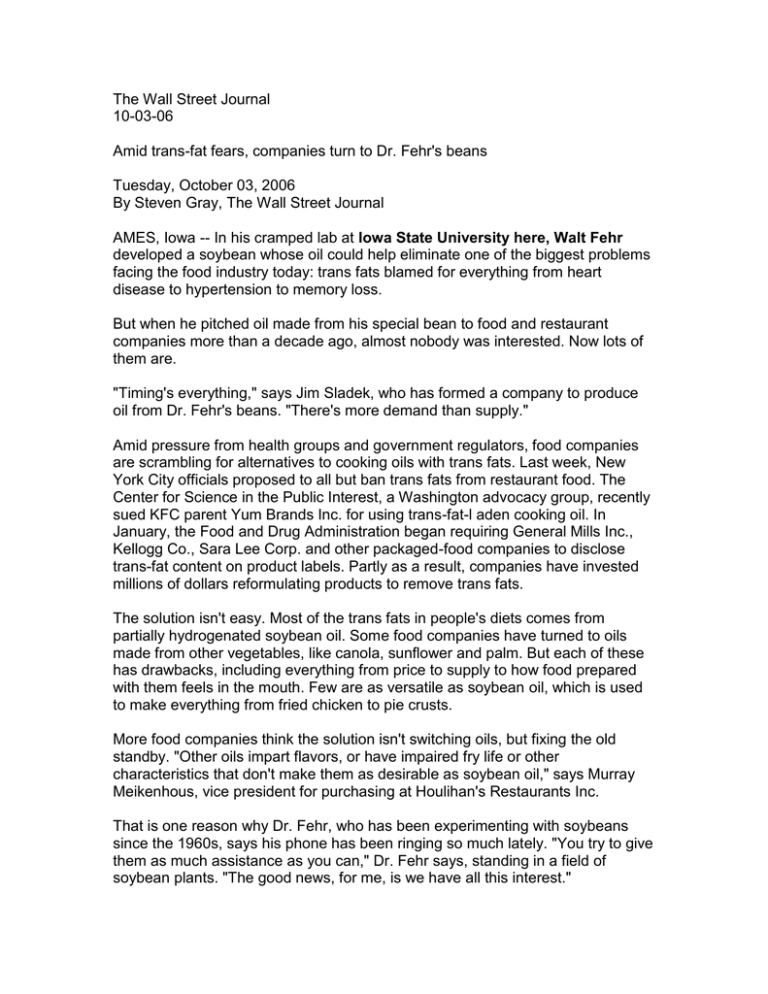

The Wall Street Journal 10-03-06 Amid trans-fat fears, companies turn to Dr. Fehr's beans Tuesday, October 03, 2006 By Steven Gray, The Wall Street Journal AMES, Iowa -- In his cramped lab at Iowa State University here, Walt Fehr developed a soybean whose oil could help eliminate one of the biggest problems facing the food industry today: trans fats blamed for everything from heart disease to hypertension to memory loss. But when he pitched oil made from his special bean to food and restaurant companies more than a decade ago, almost nobody was interested. Now lots of them are. "Timing's everything," says Jim Sladek, who has formed a company to produce oil from Dr. Fehr's beans. "There's more demand than supply." Amid pressure from health groups and government regulators, food companies are scrambling for alternatives to cooking oils with trans fats. Last week, New York City officials proposed to all but ban trans fats from restaurant food. The Center for Science in the Public Interest, a Washington advocacy group, recently sued KFC parent Yum Brands Inc. for using trans-fat-l aden cooking oil. In January, the Food and Drug Administration began requiring General Mills Inc., Kellogg Co., Sara Lee Corp. and other packaged-food companies to disclose trans-fat content on product labels. Partly as a result, companies have invested millions of dollars reformulating products to remove trans fats. The solution isn't easy. Most of the trans fats in people's diets comes from partially hydrogenated soybean oil. Some food companies have turned to oils made from other vegetables, like canola, sunflower and palm. But each of these has drawbacks, including everything from price to supply to how food prepared with them feels in the mouth. Few are as versatile as soybean oil, which is used to make everything from fried chicken to pie crusts. More food companies think the solution isn't switching oils, but fixing the old standby. "Other oils impart flavors, or have impaired fry life or other characteristics that don't make them as desirable as soybean oil," says Murray Meikenhous, vice president for purchasing at Houlihan's Restaurants Inc. That is one reason why Dr. Fehr, who has been experimenting with soybeans since the 1960s, says his phone has been ringing so much lately. "You try to give them as much assistance as you can," Dr. Fehr says, standing in a field of soybean plants. "The good news, for me, is we have all this interest." Dr. Fehr's soybeans are low in linolenic acid, which can make the oil rancid over time. To prevent this spoilage, companies suffuse the oil with hydrogen, but a side effect of the process is trans-fatty acid. Asoyia LLC, Mr. Sladek's company, says 20 food companies have already put the oil it makes from Dr. Fehr's ultra-low-linolenic soybeans in products on store shelves. Campbell Soup Co. last year began using it in some of its Goldfish crackers. "We looked at the product, and it performed everything we wanted," says Tammy Crowe, research-program manager at Campbell. Campbell uses different alternative oils depending on the flavor of Goldfish. Asoyia says about 50 major packaged-food companies, including Sara Lee and H.J. Heinz Co., are testing the oil, which is made from beans with about 1 percent linolenic acid. Both Heinz and Sara Lee declined to elaborate on their tests of the oil, citing competitive reasons. Houlihan's has been encouraged by its own tests of the oil, says Mr. Meikenhous. He says the chain expects to pick between the Asoyia oil and another similar one this week. In addition to Asoyia, DuPont Co. and Monsanto Co. are involved in soybeans low in linolenic acid. Unlike Asoyia, DuPont and Monsanto sell seeds for soybeans with between 2.5 percent and 3 percent linolenic acid to farmers. Farmers then sell their crops to companies who turn the beans into oil. Kellogg is using an oil from low-linolenic soybeans produced by Monsanto, as well as by a partnership of DuPont and oil processor Bunge Ltd. About 500,000 acres of Monsanto's beans, 200,000 of Dupont's and 40,000 acres of Asoyia's were grown this year. Monsanto expects its acerage to triple or even quadruple next year, while Dupont and Asoyia expect their acerage to more than double. "A lot of people were working on" developing a trans-fat-free soybean oil, says Robert Galloway, president of Galloway & Associates LLC, a Charleston, S.C., firm that consults with the soybean industry. "Walt was the first to bring it to market." Now, the big problem for soybeans that produce oil that doesn't require hydrogenation is making enough to satisfy demand. Qualisoy, a consortium of more than a dozen companies, associations and soybean farmers that produce trans-fat-free oil, estimates U.S. production of soybean oil made from Dr. Fehr's beans and others like it will increase to about one billion pounds in 2007 from 200 million pounds last year. That's a long way from the estimated 18 billion pounds of soybean oil that was used in the U.S. last year. Dr. Fehr, a tall, lanky 66-year-old, has spent most of his career focusing on the breeding and genetic makeup of soybeans. He grew up on a farm in northern Minnesota, and after teaching agronomy in a U.S. AID project in the Congo, began studying soybeans while pursuing his doctorate at Iowa State. During the late 1960s, Dr. Fehr went searching for a soybean with the rare trait of low linolenic acid. A few food companies were concerned about potential harmful effects of trans-fatty acids. He crossbred novelty soybeans with conventional varieties, culling the offspring for soybeans that would have high yields with low linolenic acid. In the late 1980s, after breeding a seed with so little linolenic acid that the resulting oil wouldn't require hydrogenation, he drove across the Midwest pitching it to various oil and food companies, which told him their research indicated there was little market for a trans-fat-free oil. The only taker was a Japanese company that briefly used oil from Dr. Fehr's soybeans to tame the taste and smell of canola oil. Dr. Fehr kept working. In 2003, he finished a soybean with even less linolenic acid. Around the same time, the FDA said it would require packaged-food companies to disclose trans-fat content starting this year. "That changed the whole paradigm," says Dr. Fehr. This time, he didn't bother with the food companies. He persuaded the cafeteria at an Iowa State dormitory and some local restaurants to test the oil. At Hickory Park Restaurant Co., a barbecue emporium in Ames, manager Jason Wheelock says the oil was a little more expensive than conventional soybean oil but lasted a bit longer and had no discernible effect on taste. "It's at least as good if not better than conventional oil," Mr. Wheelock says. Dr. Fehr also turned to Mr. Sladek, an Iowa City farmer who had experimented with Dr. Fehr's seeds and plants before. Mr. Sladek recruited nearly two dozen farmers to form Asoyia. Mr. Sladek, Asoyia's president, says farmers across the Great Plains are clamoring to grow the beans. There are limits to how fast the crop can spread, though. Producing enough seeds takes time. And to avoid contamination with conventional soybeans, Dr. Fehr's soybeans must be kept separate in the field and during processing. Some farmers are hesitant to grow the new seeds because they lack a popular genetically modified trait that allows the grower to douse fields with weed killers without hurting the plants. Asoyia expects to have a bean available next year that solves that problem. Dr. Fehr says he has no formal connection to Asoyia or other companies selling oil except he collects a small share of royalties paid to Iowa State. Meanwhile, he has remained busy in his lab. His latest product: a soybean whose trans-fat-free oil is even healthier than current varieties.