Farm News 09-22-06 Smithfield merges with PSF

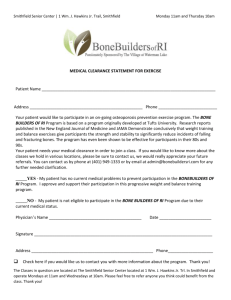

advertisement

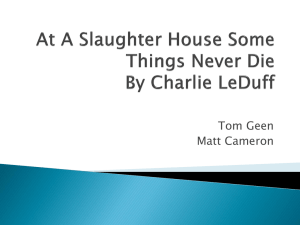

Farm News 09-22-06 Smithfield merges with PSF By RANDY MUDGETT- Managing Editor Total vertical integration has long been the goal and business structure that Smithfield Foods has followed, and now, Smithfield owns more than 1.2 million sows, clearly solidifying the company’s hold on the pork industry. On Monday, Smithfield announced plans to merge with Premium Standard Farms Inc., the nation’s second largest pork producer and sixth largest pork processor. Smithfield, who is No. 1 in both categories, said the deal will cost the company $674 million in stock plus assuming $117 million of Premium Standard Farms debt load. John Crabtree, a spokesman for the Center for Rural Affairs in Walthill, Neb., said Monday this is the most significant move by Smithfield in recent years. After an attempt to purchase IBP failed in 2001, Smithfield has since acquired several processors including Farmland Foods and John Morrell plus acquiring a good portion of ConAgra Foods branded meat business and overseas investments including the Sara Lee Corporation European meats business. ‘‘Smithfield has been clear on this from the beginning,’’ Crabtree said of the packing giant. ‘‘They want to own the sows, the baby pigs, the feeders, the processing and the label,’’ Crabtree said. ‘‘They’ve done it and this should be a red flag to our leaders.’’ Iowa Sen. Tom Harkin said Monday the merger should be closely scrutinized by the U.S. Department of Justice. ‘‘The merger involves a very substantial change in the structure, vertical integration and degree of consolidation in the U.S. pork industry,’’ Harkin said. ‘‘It obviously will have significant impacts on both independent hog producers and those who raise hogs under contract.’’ In the last round of farm policy talks, the Senate pushed for a packer ban on ownership of livestock and while the language did not make it into the final 2002 farm bill, Crabtree said it was a significant first step in getting hogs, chickens and cattle back into the hands of America’s livestock producers. ‘‘The only real solution to getting livestock ownership back into the hands of producers is to pass meaningful packer ownership laws,’’ Crabtree said. ‘‘Pork production has often been viewed as the mortgage lifter and a huge part of the family farm system. Now, corporations like Smithfield own the sows and the only role for the farmer is to build a building, accept the risk and spread the manure for the packers.’’ Iowa Sen. Charles Grassley told ag reporters Tuesday he was concerned about the proposed merger. ‘‘We have to maintain plenty of competition, particularly for the small independent producers and family farmers for them to survive. This is of great concern to Iowa,’’ Grassley said. ‘‘I cannot fathom how Smithfield, the largest and fastest growing integrator, can continue to be allowed to purchase hog operations all across the country. They have made it clear that they intended to purchase its competitors to assert dominance in the pork industry. The attitude is alarming so we should ban packer ownership of livestock and eliminate mandatory arbitration.’’ The Wal-Mart effect If the merger is approved by the Department of Justice, Smithfield will own more sows than the remaining other eight top pork producers in the nation. According to Successful Farming’s Pork Powerhouses 2006 list, Smithfield would own 1.2 million sows after acquiring Premium Standard with nearly one-half of PSF’s sows located in Missouri. Besides playing the role of the largest pork producer and processor in the world, Smithfield has also made inroads into the beef and turkey industries in recent years. The company is now the fifth largest beef packer and third largest turkey processor. Roger McEowen, Iowa State University Extension economist, said much of the problem that is leading to companies desiring a vertical integration system is related to the race to the bottom for food prices. ‘‘Looking long term, a vertically integrated system in the livestock sector relates to a loss of independence for the family farmer,’’ McEowen said. ‘‘Producers lose their portion of the open market system because corporations are experiencing the Wal-Mart effect.’’ McEowen said the ‘‘Wal-Mart Effect’’ or a system that requires buyers to buy ever-increasing numbers in order to maintain efficiency, is forcing companies like Smithfield to become more and more efficient. In turn, companies like Wal-Mart desire to purchase products in bulk at cheap prices with a quick turnover and quick profit. ‘‘You have to be big to get your product in stores like Albertsons or Wal-Mart,’’ McEowen said. ‘‘These big retailers charge slotting fees just to allow a processor to sell the product at their store. They have such buying power strength, the system forces companies to cut costs and vertical integration helps cut those costs.’’ McEowen said the current political structure does not lend itself to pushing for a ban on packers owning livestock. ‘‘If our society desires a change and wants to see small farming return, then it could happen,’’ McEowen said. ‘‘But, right now, and even if the Democrats took control of Congress, I still do not foresee a change in thinking when it comes to ending the vertically integrated systems that are now commonplace.’’