Inside Higher Ed, DC 09-26-06 The Clarity Gap

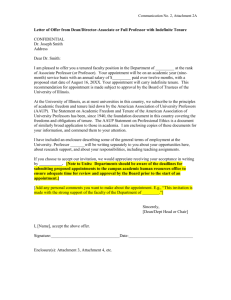

advertisement

Inside Higher Ed, DC 09-26-06 The Clarity Gap No one expects earning tenure to be easy. But while revising a course, or trying to finish up that book or grant application, should a junior professor at least know what it will take to grab academe’s brass ring? A new study of four-year colleges and universities — one of the most ambitious ever of the attitudes of young professors — finds that there is a notable gap between female and male academics in their confidence that tenure rules are clear, with men feeling more confident. The study also looked at many other issues — and found numerous instances (some consistent with previous studies) suggesting that female faculty members are less satisfied than their male counterparts with certain college policies and the climate of their workplaces. In a number of cases where there is a gender gap on attitudes, there is not a notable race gap. Attitudes on various issues such as collegiality may also be more important than previously thought, according to the study. While participants were not asked to rank the relative importance of various factors in determining their overall job satisfaction, researchers did regression analyses looking at overall satisfaction and answers on various questions. Those analyses suggested that young professors care more about climate, the nature of their work, and tenure systems than they do about compensation. The data released Monday come from the Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education, or COACHE, which is run by the Harvard University Graduate School of Education. For its study, the project surveyed 4,500 faculty members at 51 colleges and universities in the United States. Only national averages were released to the public Monday, but participating colleges are also receiving institutional averages, and the averages for selected peer institutions (without learning which average correlates to which peer institution). The idea is that colleges can then evaluate their results and identify areas for improvement. The results on tenure clarity surprised several experts, and the researchers who did the study said that they didn’t know exactly what the gap meant. “I think we’re seeing things that in some cases we’ve seen before, and we’re finding that problems haven’t been fixed,” said Cathy Trower, director of the study. “The notion that women are less clear on tenure raises all kinds of questions. What does this mean? Are they not getting information? Are they more insecure about their knowledge? We just don’t know.” On clarity, participants were asked to evaluate policies on a scale of 1 to 5 (very unclear to very clear). Clarity of Tenure Policies Clarity of Female Male Process 3.58 3.67 Criteria 3.51 3.55 Standards 3.16 3.23 Body of evidence 3.41 3.50 All of those differences meet the test for statistical significance. But when comparisons were done for white and minority faculty members, only one category had a statistically significant difference: Minority faculty members felt standards were more clear than did white faculty members. When the study got more detailed, it appears that the gap in clarity is focused entirely on one issue: research. When asked if the process and policies were clear with regard to other factors (teaching, advising, being a colleague), there were not statistical differences. But on research, the men were more confident that they understood what was expected of them. And in answers to other questions, men were more likely than women to consider tenure expectations to be reasonable. Beyond issues of gender, there is also the question of why such an important test for young faculty members as earning tenure isn’t entirely clear. A score of 4 would mean “fairly clear” and averages were below that. Georgia Nugent, president of Kenyon College, said that the data reinforce her view that there is wide variation on how specific different colleges get in helping junior professors navigate the tenure process. Nugent’s career until she moved to Kenyon was largely at Brown and Princeton Universities. “I was incredibly struck when I came here by the difference between what I was familiar with at Princeton and Brown and the clarity of written standards here. My feeling was that at Princeton and Brown, both of which had tenure processes I went through myself, it was ‘Do as much as you possibly can and I’ll let you know,’ ” she said. At Kenyon, she said, departments have some leeway in setting priorities for tenure — how teaching should be weighted vs. research and so forth, but they are very specific on what those weights are. Some departments, she said, care about whether research involves students, and they say so. Others are more concerned about how research is presented and received in national disciplinary groups, and they say so. Mary McKinney, a clinical psychologist who coaches professors on their careers, said that she was surprised by the gender gap on clarity issues because “I talk to men who feel like they are floundering around over these issues, too.” McKinney said that the gap (and mid-level rankings over all) should worry people who care about young professors’ well-being. “So many rules aren’t explicitly stated, such as that one lukewarm recommendation can kill your chances,” she said. Assistant professors need to know these rules, to make sure everything is as favorable as possible to their chances. As to the gender difference, she said that some trends she sees may be more pronounced among women than men. “I often find that some junior professors are hesitant to ask people directly for information: What do I have to do to get tenure? May I see your tenure packet? There is a sense from some that one should already know this and it would be an embarrassing to ask,” she said. McKinney also noted that in departments where there are relatively few women, many report difficulty in finding good mentors. “If men get the mentors, it’s those mentors who would tell them, ‘The guidelines are vague, but here’s what you really have to do. Here’s how many articles you need to publish. Here’s the grants you’re going to need to have.’ “ One person who was not surprised at all by the gender gap was Jeffrey M. Duban, a New York lawyer whose specialty is suing colleges for discrimination in tenure and other employment disputes. “This is new confirmation of the bias against women in academe,” he said. Duban said that a very large share of his cases deal in part with lack of clarity over expectations. The most common way this comes up, he said, is when a woman receives great annual reviews, and a great three-year review, and then comes up for tenure and — all of the sudden — the reviews get critical. In the absence of clear guidelines, people will rely on their interim reviews, he said, and sudden changes suggest a problem in defining the rules. On Monday, while being interviewed for this article, Duban said he was negotiating a settlement on behalf of a female faculty member in just such a situation. The lack of clarity about tenure, he acknowledged, does get him more customers. Others cautioned that some uncertainty — and perhaps more uncertainty that many would like — is inevitable in the tenure process. “It’s never so simple as a checklist that you can look at and say ‘Yes, I did it’ or ‘No I didn’t.’ It’s an interpretive one, by peers. So your peers are looking at your performance in multiple categories,” said Susan Carlson, interim provost of Iowa State University. Carlson said she worried that the data suggest that colleges aren’t doing well enough at communicating with junior faculty members. But she stressed, “We’d all like to say it’s X number of publications and X number of scores on teaching evaluations, and that doesn’t do it.” Satisfaction With Policies and Culture The survey also asked faculty members for their views on a number of institutional policies and the climate. Consistent with other surveys, women reported lower satisfaction levels than did men on such matters as balancing family and professional responsibilities. On satisfaction with policies, there was only one category — the availability of formal mentoring programs — on which there was a statistically significant difference in the ratings of white and minority professors. White professors were less likely to see the policies as effective. When policies were compared by gender, female professors were less satisfied than men with the availability of child care, upper limits set on committee work, and upper limits on teaching loads. Men were less satisfied than women with “stop the clock” tenure provisions. Nugent of Kenyon said that data like this can reinforce college efforts. For example, she said that the one area where Kenyon scored poorly was on child care. But she said that — after years of discussion — the college has started setting up a child care facility for employees. On overall culture, men reported being more satisfied than did women, while there was no statistical difference between white and minority faculty members. On “global satisfaction” with their jobs (based on combining responses to questions), the study found that men were slightly more satisfied than women, and that white faculty members were more satisfied than minority faculty members. But she added that black and white scores were quite close and that scores of Asian faculty members — who were less happy — brought down the overall minority satisfaction level. Taken as a whole, faculty members indicated that they are pleased with their jobs, with 78 percent saying that they would accept their current position again. Nearly half rate their work place as “good,” while only 8 percent say their institution is a “bad” or “awful” place to work. Trower, the project director, said she hoped that colleges would pay attention to the finding that satisfaction was determined more by non-salary items than by salary. “One of the results is that you can increase faculty members’ compensation and you may not make them more satisfied,” Trower said. “If you can fix where junior faculty members spend their time and work — in their departments — you are a lot farther down this path of keeping your talent.” That’s an encouraging message to colleges that may not be able to compete with the wealthiest with regard to salaries, but can do other things for employees. Nugent said that her board has set a goal of having faculty salaries in the top quintile nationally, and that the college is able to do that, but sometimes must struggle to do so. Other things are easier to do. She said that the college made the time between Christmas and New Year’s Day a paid holiday for employees, started the child care facility, and has added funds for faculty research and international travel, among other things. It’s not surprising, she said, that professors would find such policies important, given that faculty members have already made an againstthe-grain choice to pursue careers in which advanced education isn’t rewarded with society’s highest salaries. “If faculty were people who really cared primarily about money,” she said, “they wouldn’t be in this business.” — Scott Jaschik