Des Moines Business Record 09-03-06 Painting a pretty picture

advertisement

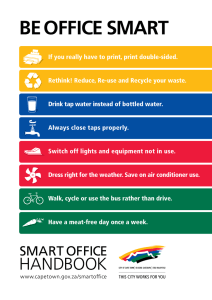

Des Moines Business Record 09-03-06 Painting a pretty picture By Sarah Bzdega sarahbzdega@bpcdm.com Front porches extending to wide sidewalks shaded by tall trees. A main street within walking distance teeming with small shops. Green spaces surrounded by ponds and trails. These pictures seem to signal a return to the idyllic neighborhood people nostalgically remember from childhood or embrace from stories told by older generations. Ankeny's Prairie Trail development is one of several projects in Greater Des Moines latching on to "new urbanist" or "smart growth" principles as a way to attract people longing for the old days. They offer planned communities as an alternative to suburbia and an opportunity to create a neighborhood based on residents' values. But although people are becoming more interested in these communities around Des Moines, some experts stress that they are only an alternative, rather than a solution, to Des Moines' ever-sprawling developments. In addition, issues with size, people's behavior and fast-paced growth may outweigh some of the benefits. Community planners, city officials and residents might have to lower the expectations they have placed on the future of these neighborhoods. Benefits of smart growth Recognizing an increasing interest in smart growth communities, developers have been willing to invest more time and resources needed to plan a community from beginning to end. "It's a model that Des Moines has not really seen in its marketplace," said Dennis Reynolds, Ladco Development Inc.'s development designer and lead designer of the Village of Ponderosa, a 95-acre smart growth community. "The fact that neighborhoods like Beaverdale are so desirable is a good indication that people really want this kind of walkable development." "Many people chose the Ankeny lifestyle because they want to be active and socially connected," said Ankeny City Manager Carl Metzger. "This Ankeny attribute was confirmed during the Prairie Trail visioning process and in the 2005 citizen survey. In the survey, 78 percent of respondents rated Ankeny's sense of community as good or excellent." The smart growth and new urbanism movements arose during the late 20th century as reactions to the suburban communities that sprung up after veterans returned from World War II. Suburbs were designed with the car in mind, and developers built cul-de-sacs feeding into a few main roads that led to commercial and industrial development farther away. Smart growth and new urbanism, on the other hand, promote designs that rely less on car travel, encourage social interaction within a community and have small commercial development within walking distance of residences. Smart growth essentially means "better-planned growth"; it attempts to fill in undeveloped or abandoned spaces within existing suburbs or urban areas with higher-density development, such as multifamily housing and professional offices above retail. Some of its other components include preserving environmentally sensitive areas, revitalizing historic downtowns and residential neighborhoods, and giving people the option of walking, biking or taking public transportation. "Part of it is an expanded way of thinking about what you're doing as opposed to just looking at developing this piece of property," said Neil Hamilton, director of the Agricultural Law Center at Drake University, who helped host a conservation design workshop at Drake last May. "You have a broader set of what the whole neighborhood is going to look like." In addition, Hamilton said, you can take into account certain values and how they connect to a person's lifestyle, such as understanding the importance of physical exercise and promoting it with trail systems. Supporters also see this kind of community as having a longer lifespan than typical suburban subdivisions. "We need to have choices and build things that our grandchildren are proud of," said LaVon Griffieon, co-founder of 1,000 Friends of Iowa. "Our grandparents did it for us; they built communities with beautiful buildings downtown. They built buildings to last for us and we're building Blockbuster videos that may have a 20year shelf life." New urbanists are smart growth proponents who call for a return to pre-World War II town planning, often using the model of a town center surrounded by close-knit neighborhoods. Started by Andres Duany and his wife, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, the first new urbanist development was a Florida resort town called Seaside (the setting of "The Truman Show") and since then the concept has expanded to other communities, mainly on the coasts. Instead of cul-de-sacs, new urbanists advocate a grid pattern for an easier flow of traffic with narrower streets, garages set in back alleyways, front porches to encourage interaction and diversity in housing. "Everything is scaled so that it's comfortable to walk around the streets and comfortable to interact with neighbors sitting on porches," said Michael Martin, an associate professor of landscape architecture at Iowa State University's College of Design. Those who believe in smart growth and new urbanism see a huge benefit to this kind of design. Mixed-use development, for example, conserves land and other valuable resources by putting all the resources into one area rather than zoning land into commercial, residential and industrial sections. "It doesn't make sense to build streets and facilities you use 10 hours a day and a whole other set of other facilities for where people actually live," Hamilton said. "Having people live where they work and shop where they live are the underpinning ideas of new urbanism." Reynolds said that studies show that using one parking lot for multiple activities can reduce parking lot space by 25 percent, which not only means less pavement but also reduces heat emissions and runoff. Keith Summerville, an assistant professor of environmental science and policy at Drake University and member of Des Moines' Urban Conservation Committee, also sees it as a benefit because it brings more green space into a community. One of the advantages is looking at back yards not as individual units, he said, but as a continuous entity that can serve everyone, which creates an environment attractive to wildlife. Also smart growth and new urbanist planners often use natural ways to solve problems through conservation design, such as managing stormwater runoff in residential neighborhoods with bioswales, a subsurface and plant life filtration system that collects groundwater, instead of sewers. "If you think of it in an artistic sense," said Summerville, "it's softening the edges by bringing in natural ecosystems into areas traditionally where you used engineering to solve problems." These natural systems are further supported by walkways that allow people to access several parks without driving. The Village of Ponderosa will have seven miles of walkways within the 95-acre development, said Reynolds, which is a lot for a development its size. Issues with design in practice The ideals of smart growth and new urbanist communities might appeal to a growing number of people, but the real-world implementations of those ideals might not live up to all their expectations. In promoting an alternative to suburban sprawl, said Martin, some new urbanists are quick to disregard that many people are still interested in suburban communities. As an example, Martin says that Somerset Village, a new urbanist type of community, and Northridge Heights, a suburban development, started next to each other in Ames. Northridge offered bigger lots, cul-de-sacs, easier parking and an open bike path system behind the houses, while Somerset offered multifamily housing or smaller single-family lots. "A lot of people looked at the same price for a house in the two places and [Northridge] looked like a better deal," Martin said. "It's what we're used to." "[Smart growth developments] can give people options," Hamilton said. "There are opportunities to use new-urbanist-type approaches downtown as well as build suburbs with the idea that people have choices." Part of the attraction of suburban developments, says Martin, is the safety cul-desacs provide for children. New urbanists see streets as social spaces, he says, but parents are not going to let their children run free out there. One solution for new urbanists would be to stress the importance of alleyways as being a social space and not just a location to park the car and leave the trash, said Martin. The people that tend to be interested in smart growth communities are often Baby Boomers and young couples who are seeking more convenient, friendlier neighborhoods. Size may also be a factor in determining how effective a smart growth community will be. "Part of it is when you plan large swaths of land, you can have all the best intentions," said Martin, "then people make different choices. They're hard to plan with any real knowledge of what will happen with people. I don't have a lot of faith with 1,000-acre plans. I'm more interested in local-scale neighborhoods because they're easier to understand and more predictive of how people will live day to day." Martin said if given an area the size of Prairie Trail, he would create multiple communities, so that they are easier to walk around and tighter-knit than one large neighborhood. He believes in new urbanist founder Duany's dictum that the ideal neighborhood is approximately 160 acres with a distinct center that is no more than a five-minute walk from a clearly defined edge. He believes that cities should grow by adding one neighborhood of this size at a time. Size was a big consideration for the Village of Ponderosa. "We've tried to concentrate a diversity of activities within walkable distances, approximately 1,000 feet," Reynolds said, "so you can walk to the grocery store or bakery, walk to work, walk from the office to do some banking or another employment. The concentration of activity allows it to be effective." Still, says Martin, it's hard to predict people's actions within planned communities no matter the size. Although new urbanist houses have front porches to encourage interaction, he says, "they're probably in the basement in the air conditioning playing video games." In addition, in some of these communities, such as a Sacramento suburb, people continued to work outside the community and as a result they still became bedroom communities. In addition to size, population density is also important to sustaining a vibrant town center, says Martin, and in the past, commercial development has been hard to sustain. A community the size of Somerset, for example, struggled to keep commercial enterprises, he said, in part because the neighborhoods are still being developed after 10 years. A café has done well, he said, because people from outside the community also patronize it. Reynolds is relying on a high density of people in the community to support business as well as visitors who shop at Jordan Creek Town Center or live around the West Glen area. He also said his company is being selective in what businesses they bring in. "We are seeking out tenants that help support and reinforce each other," he said. Wait and see People like Griffieon and Summerville also believe though planned growth is better than suburban sprawl, it doesn't replace having no development. "There are ways to make development more sustainable in an ecological sense," Summerville said, "but it is not a replacement for having large protected areas." Griffieon, who lives on a farm north of Ankeny, urges planners to develop only when necessary. "[Prairie Trail] would be smart growth if it was truly necessary development," she said, "but Ankeny has about 1,000 houses sitting for sale." In addition, Griffieon notices that some developers are calling their communities "smart growth" because they have one or two of the smart growth components, but are ignoring some of the other 11 principles, along with developing on farmland instead of in undeveloped space within a city. She also has noticed that smart growth communities have not set an example for other development and slowed outward development, using Prairie Crossing in Illinois as an example. Experts, however, are still waiting to see the full effects of smart growth and new urbanist communities because many are less than a decade old or are still being built. Hamilton sees these planned developments as an evolution, not an end. "We're trying to think more creatively about how to use zoning and planning tools to achieve certain objectives," he said. One option is to look at Oregon, which has a "progressive land-use policy," Martin said, and consider ideas such as drawing a circle around the city and deciding not to develop past that line until the inside of the city is fully developed. Martin also stresses that people should wait and see how these planned communities fully develop. It takes a while, he said, for the trees to grow over the streets and the land to be fully developed to the point where it may be able to sustain more commercial growth. "We have to give it time," said Martin. "We can't be too quick to judge."