COPLEY SQUARE: ITS FULL POTENTIAL

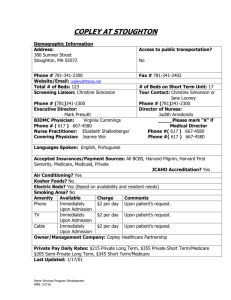

advertisement