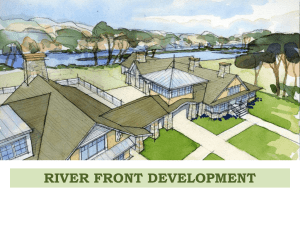

URBAN AND POTENTIALS

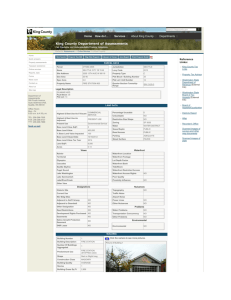

advertisement