Supreme Court of the United States In The

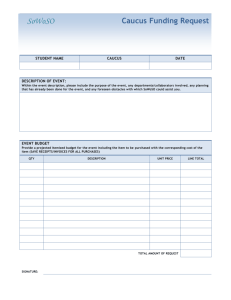

advertisement