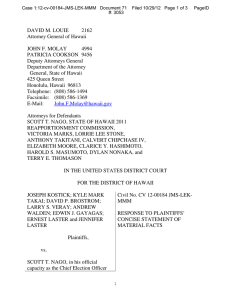

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF HAWAII )

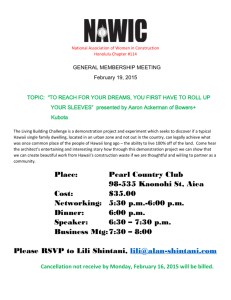

advertisement