Of Counsel: DAMON KEY LEONG KUPCHAK HASTERT Attorneys at Law A Law Corporation

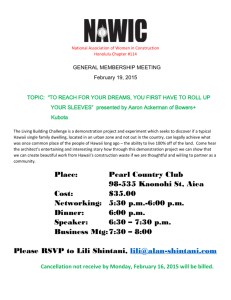

advertisement