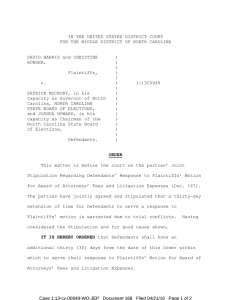

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WILLIAM WHITFORD, ROGER ANCLAM, )

advertisement