APPENDIX

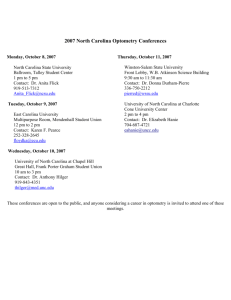

advertisement