IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SAN ANTONIO DIVISION

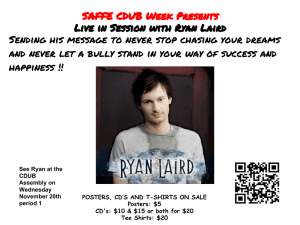

advertisement