IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SAN ANTONIO DIVISION

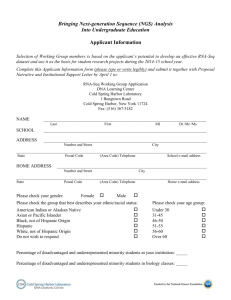

advertisement