C & B ,

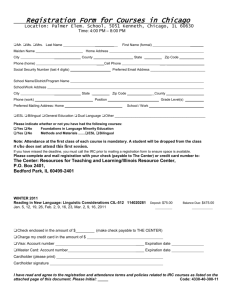

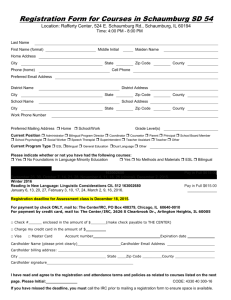

advertisement