Dr. Lorin Anderson Podcast Interview Transcript—Part One Interview conducted by Dal Edwards

advertisement

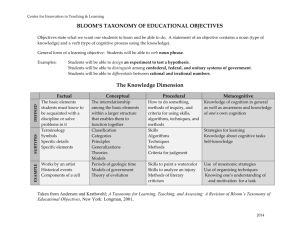

Dr. Lorin Anderson Podcast Interview Transcript—Part One Interview conducted by Dal Edwards April 8, 2009 12:15-1:00 (Music) Lorin Anderson is a distinguished professor emeritus at the University of South Carolina. He has researched and published in the areas of classroom instruction and school learning, effective programs and practices for economically disadvantaged children and youth, the allocation and use of school time, and effective assessment. He is the senior editor and contributor to A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives published in 2001. He is currently consulting with North Carolina’s Department of Public Instruction in the revision of the content standards. (Music) We are here at the Department of Public Instruction with Dr. Lorin Anderson who is in the middle of a day consulting with various sections of DPI on the standards revision process. Dr. Anderson, thank you for agreeing to do this podcast interview with the Social Studies section here at DPI. We appreciate your time. Question: "Why was there a need for a revised Bloom's Taxonomy (RBT) and what is the difference between the old taxonomy and RBT?" Anderson: (1:30) Well, let me set it in a kind of historical context. I was a student of Bloom back in the early seventies. And in 1994, I was asked by the National Society for the Study of Education to edit a book on a retrospective view of what was then known as Bloom’s Taxonomy--the original. And we put together a bunch of chapters where we looked at it in both a historical and contemporary context. And one of the authors that we asked to write was a man named David Krathwohl, who was one of the participants in the group that put together the original Bloom’s taxonomy. Bloom was alive at the time and he actually wrote the first chapter and it was the last thing he published—was the chapter of that book. The book went over very well, which suggested to a lot of us that there…that it was still being used and recognized. And David Krathwohl contacted me and asked if I wanted to work on a revision of the taxonomy because he still had the rights to the original publisher. So we talked for a while and we said it was too big a job just for the two of us to do it. We needed to bring together experts in various fields, like cognitive psychology, curriculum, assessment (and) evaluation. When you look at the revised Bloom’s taxonomy, there are two editors—David and I—and there were six authors. They wrote different sections of it and we tried to kind of put it together. The basic reason to do it over was that there had been a lot of work done in terms of how to classify objectives between 1956—when the original taxonomy was written—and 1996 when we started to meet. And so we reviewed a lot of that work and it turned out that there were around twenty different attempts to come up with different category systems and different classification systems—all going back to the original taxonomy. So they were all attempts to update it. And so we used all of that information to kind of figure out what the new, improved version of the Bloom’s taxonomy would be. And one of the things that stood out was it had to be two-dimensional. The original taxonomy was one dimensional—knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation (3:45). The reason it had to be two dimensional was because of the structure of objectives. An objective is simply a statement of what we intend a student to learn as a result of the instruction we provide. As we looked at the statements of these objectives, we realized that they all had a common format—subject, verb, object. And the subject was always the student, or students. And…and elementary teachers had it really codified. It was always TLW, which is “The learner will”, which was the student, BAT, which was “be able to”. The next one after the TLW BAT was a verb. They’ll comprehend. They’ll use. They’ll analyze. They’ll make judgements about. There was always some verb. And then there was an object to the sentence. And the object tended to be the content. So it was the “subtraction algorithm”, it was “forms of poetry”. And because of that structure, “SVO”, that we needed one dimension for the “V” and one dimension for the “O”. And so we realized at that point in time, that the original taxonomy, even though the forms were nouns—knowledge, comprehension—they really were intended to function as verbs. It would have been better if they had written them—“know”, “comprehend”, “apply” and so forth. So we took…those six categories of the original and we made them into verbs. (5:11) And we changed some of the terms—that “know”…students will know things, there were so many different ways of what people thought of “knowing”. So we changed that to “remember”. Students will “remember” things. And we changed “comprehension” to “understand”. A student will “understand” things. Students will do things with what they know and understand, we call that “apply”, which was a direct translation from “application”. Then came “analyze”. Then we got to the top and we realized that “synthesize” was not particularly communicative to teachers. As we talked more we realized that “create” is really what “synthesize” meant—putting together things in new ways for a particular purpose. And if we had “create”, we actually moved “evaluate” down one. Evaluation used to be at the highest of the original, now it’s second to the highest in the revised. So you just need to learn a new mantra. Instead of “knowledge”, “comprehension”, and so forth, you have to learn “remember”, “understand”, “apply”, “analyze”, “evaluate”, “create” (6:15). The old part of the objective…the object part of the objective was more problematic, because we had to find some way of cutting across subject areas. All content is subject specific. The science content is not the same as the math content. It’s not the same as the language-arts content and art content. So we went deep into cognitive psychology and we came up with what we called “types of knowledge”. And there were four types of knowledge that we came up with. They are “factual knowledge”, which is kind of knowledge of facts and terms; “conceptual knowledge”, which is knowledge of categories, and relationships among categories. High levels of conceptual knowledge are things like theories, structures, and so forth; “procedural knowledge”, which is really knowledge on how to do things. Procedural knowledge is typically sequential—first you do this, then you do that, then you do that, and so forth. Then we added a fourth category called “metacognitive knowledge”—which is knowledge that is unique really to the learner. It’s knowledge of how a particular learner approaches a given task in schools. It’s knowing whether you’re better with multiple choice tests, than essays. It’s knowing what your interests are—knowledge of study strategies, how you study best. A lot of what we call learning styles is really metacognitive knowledge—it’s knowing that I prefer to learn by myself as opposed to around other people. Or I need a certain amount of quiet, because I’m easily distracted by noise, just even in the hall. (7:48) So we ended up with a two dimensional table. One dimension we call the cognitive process dimension. The second one we call the knowledge dimension. The cognitive process dimension helps to understand the verb part of the “subject-verbobject”. And the knowledge dimension helps to understand the object part of the “subject-verb-object”. And the system is set up so it’s equally applicable across subject areas—whether its reading, writing, math, science, art, music, auto repair…And also equally applicable across grade levels—whether you’re talking about second grade, fifth grade, third grade, eighth grade, high school. So we tried to make it in a way that was the most generalizable possible. And we tried to use terms and words all the way through it that were teacher friendly. Once a teacher understands procedural knowledge as a sequence of steps it’s…and teachers do talk about, “I teach procedures”, or “I teach algorithms” if you’re in math. Or “I teach methods” if I’m in math. Or “I teach techniques” if I’m in music. But they’re all procedural issues. The hardest thing that teachers have to, to understand is the difference between factual knowledge and conceptual knowledge. That’s the one we struggled with. (Music)