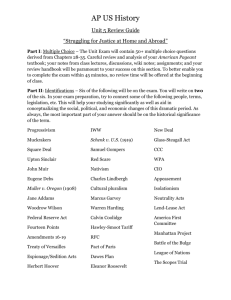

WRITING ACROSS THE CURRICULUM HANDBOOK

advertisement