09 by Aida Spinazzola 1985

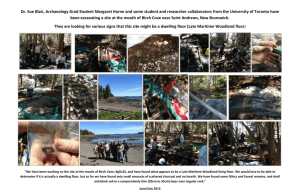

advertisement