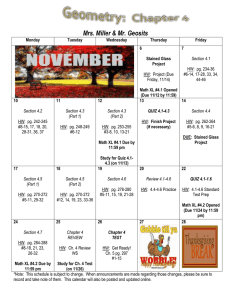

STAINED GLASS:

advertisement