ate on a Sunday

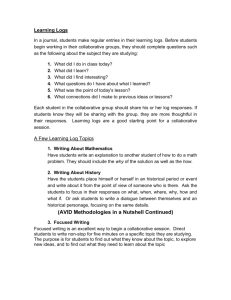

advertisement

By StevenE. Daniels,GreggB.Walker,MatthewS. Carroll,and KeithA. Blatner burnedthrough September. In lateAugust,theWenatchee Na- ter and function.They alsoanuc•patedthatforestrestoration activines tional Forest launched a short-term rehabilitation effort to thwart ero- could be controversial, and that d•f- ate on aSunday inJuly 1994, lightning storms movedeastward across the Cascade Mountain rangeof CentralWashington. They ferentviewsaboutfire recoveryand followed in the wake of record-break- sion,reduce floodingrisk,andmain- foresthealthprovidedthe potenual ingsummer temperatures andencoun- tain publicsafety.Someforestareas for outright conflict.There are a that the staff teredforestssufferingfrom yearsof wereclosedto the public.Severely numberof techniques drought-like conditions. Theyignited burned hillsides were seeded and fer- might have employed:transacuve manyfires 41 in theWenatchee Na- tilized. Drainageswere shoredup planning(Friedmann1973), stratetional Forest alone. with hay, rock, and check dams. gic perspectives analysis(Dale and The fires thrived becauseof a numBurnedtreeswere cut as part of a Lane 1995), searchconferencmg ber of factors:unusuallydry forest contourfellingprocess to reducesed- (Dieruer and Alvarez 1995), and so conditions, a largevolumeof natural imentation from overland flow. forth. KeyWenatchee NationalForfuels,steepterrain,andstrongwinds Roadsweremodifiedto providefor estpersonnel wereawareof the aucollaborative learning with gustsup to 50 milesperhour. manageable waterflowsduringwin- thors'previous When theybrokeout, fewlocalfire- tersnowmeltandspringrains. applications elsewhere in the region, and solicited their involvement. fighting resourceswere available. Much of the firefightingequipment Long-Term Thispaperdescribes thecollaboraForestHealth based in the Pacific Northwest had As theseemergency rehabilitation tive learningapproachusedin the beendeployed to firesin the Rocky effortsproceeded,forest-leveland Wenatcheefire recoveryplanning Mountains, which had already rangerdistrictmanagement beganto The authorshavereportedotherapof thisapproach elsewhere claimed16 lives.Duringthefirstfew planfor thelong-termhealthof the plications daysof the Cascade-region fires,ex- damaged forests. They realizedthat (e.g., Daniels and Walker 1996; USING COLLABORATIVE LEARNINSI treme fire behavior hindered contain- rehabilitating the forestsrequireda Walker and Daniels 1994a). Nocomprehensive firerecovery planning where, however, has collaborauve effort. This effort needed to be learningbeenappliedascomprehengroundedin ecosystem-based man- sivelyasin thisinstance. agement--combining thebestavailablescientificknowledge with thor- FireRecovery Planningand oughpublicinvolvement. To drawon Collaborative Learning the best available science,the forest (WenatcheeNational Forest1994). Collaborative learning (CL) isa rein publicparticipauon BytheendofJuly,foursignificant leadershipsupportedthe develop- centinnovation fires were burningin the Chelan mentof a science tovarious teamorganized by theorythathasbeenapplied Countyportionof theWenatchee Na- the Wenatchee Lab of the USDA For- community-or ecosystem-level decitionalForest: theTyeeCreekFire,the est Service Pacific Northwest Resionmaking processes. The technique Rat Creek Fire (which was human- search Station. The science team isgrounded in thetheories of conflict caused), theHatcheryCreekfire,and would incorporatedata from these management andsystems thinkingAs the RoundMountainfire. Together andpreviousfiresto determineman- a result,it iswell suitedto dealwith (1) thesefires burned more than 181,000 agementscenarios thatcouldaddress the rancorous rhetoric and conflictual health,sustainability, contextthat characterizes contempoacres, temporarily closed majorhigh- forestecosystem ways,destroyed 37 homes,involved andbiodiversity. rarynaturalresource debate, and(2) the complexity of landmanmorethan8,000firefighting personnel The nationalforeststaff recog- fundamental from 25 states,and costalmost70 milnizedthatthefirerecovery publicin- agement situations. The application of lion dollarsto suppress (Wenatchee volvement scenario offeredanoppor- collaborativelearningto the WeNationalForest1994).Althoughthe tunity for innovation.Primarily,the natcheeNationalForestfire recovery situation (referredto hereafteras the firesweregenerally contained by mid- Forest Service wanted to consider for forestcharac- FireRecovery August,some high-elevation areas publicexpectations Collaborative Learrang mentefforts. Manyseasoned firefightersencountered unpredictable andseverewildfireactivity;somereported fires makingdramatic,rapid runs downvalleys--consuming morethan 81,000 acresin a two-hourperiod 4 August1996 IECO ERYPLANNIH$ Project,or FRCL project)proceeded With thisknowledge of theforest, Action 2--Collaborative throughseveral steps between October the fires, and affected communities, Learning Workshops Citizenworkshops werekeycompo1994andApril 1995. theauthors designed andconducted a Thefirstset two-day "CollaborativeLearning nentsof theFRCLproject. Action 1--Collaborative workshops waspartof theWeTrainingCourse"for 25 Wenatchee of these NationalForest employees. FRCLpro- natchee NationalForest's "pre-project" LearningTraining depended in parton their effort--they generated publicinputbeThe firststageof the FRCLpro- jectsuccess ject emphasizededucationof both understanding of specific firereandacceptance of the forethedevelopment projects thatwouldbesubject to the collaborative learningfacilitators collaborative learningprocess itself, covery and the Wenatcheepersonnelwho particularly among theproject-level in- National EnvironmentalPolicyAct were (ID) teams.The train- (NEPA) review.The workshops wouldbe involvedin planning. The terdisciplinary authorsspentconsiderable time on ingcourse to emphasize bothscienincludedpresentations on constructed theforestshortlyafterthefires,meet- softsystems methodology, situation tificexpertise andcitizeninvolvement. ingrangerdistrictpersonnel, making mapping, andlearning. It usedsmall The projectincludedfour full-day presentations aboutthe project,at- groupactivitiesto teachparticipants workshops: threein ChelanCounty tendingvariousmanagementteam aboutsomeof thestages of thecollab- andonein thegreater Seattle area. meetings, andparticipating in field orativelearning framework. TheseacWorkshop design began withtheastripsinto theburnedareas. Aspartof tivities involved ID team members sumption thatpeopleneeda common a largerproject,the authorsalso fromspecific rangerdistricts working baseof knowledge aboutfirerecovery beforetheycaneffectively partichelpedtrain andsupervise graduate onderisionmaking situations thatwere issues students who conducted more than meaningful to them,suchasAdaptive ipatein decisionmaking. To thatend, 120 interviews in the fire-affected werepreceded by"issue Management Areaplanning,water- theworkshops communities of Leavenworth, Enevenings"--meetings at shedassessment planning,or recre- presentation ation area construction conflict. whichthepubliccouldlearnaboutistiat,andChelan,Washington. Photo byGrant Gibbs Journalof Forestry 5 coverysituation--includingenough materialsothatall participants could seetheirinterests andconcerns represented. A contmon behavior when dealing•vithsituations ascomplexas firerecovery isto choose a singlecause and attributeall of the negativefeaturesof the situation to it ("it's all due to badfiresuppression management"; "it's all dne to too nmch fuel material" "theforest will beharmedif salvaged"). A properlyconstructed mind map showsthat there are many possible causes andthusmanypossible changes After thesummer firesof 1994, thecharredhillsof the P(Onatchee Nat,onal that conld render intprovedforest health.It presents a "systems" viewof Forestwerele]}vulnerable to erosion andflooding. the problemsituation,encouraging suessuchasfireecology andfire'sef- thatwerecomplete opposites. Butthere participantsto think systemically about concerns, interests, needs, and fectsonwildlife,fish,vegetation, recre- was also a substantial set that indicated ation, and tourism. Presenterscame a morenuanced approach. Forexample, situationimproventents. Individualandsmallgrouptasks. A fromfederal andstateagencies andin- one individual's "best" was: cludedother expertsfrom the local participant-centered active learning hnmcdiatc salvage of bnrncdtimtasksidentifyingthemesof concern area. The subseqnent day-longCL bet done with state-of-the-art technoland interests--provided a transition workshops emphasized informaldisogy.Putmostpriorityon pinestands cussion morethanformalpresentation. and loggingon snowycover.Next, from commonunderstanding to acmoveinto fir standsfbr salvage. Use Theseworkshops •vereopen to the tion. This requiredthe participants these revenues to regenerate a newtbrpublic and were publicizedwidely. to selectaspects of the fire recovery est and maintain forest health into the situation, as shown on the mind Theirgoalwasto identifypublicissues f•tnre. Insect and disease control, map, that concernedthem and/or regarding foresthealthandallowthe chippingn,uncrchantable material. that they thought could be intparticipants to developmanagement andblowingon thesoilformnlch. improvements that could be underproved.Fhisactivityparallels"issne Another individual's "worst" case identification"in traditional probtakenaspartof fire recovery projects (fig.l, p. 8). The participants engaged scenario included: lemsolvingand "focusingon interin a series of activities to promoteunests"in mutual gains negotiation l remendot, shnmanimpactonthe (Fisherand Ury 1991). Participants derstanding of issues andconcerns. land, snch as more roads, soil COlnBest and u,orst views and situation identifiedconcerns individually,and paction,andotherdamage; spread of mapping. In additionto the issueprethen discnssed them initiallyin pairs, ,•oxions weeds:lossof big treesand and then in groups of 4 to 8. The sentations, two activelearningtasks snags andlogs(takescenturies to rewere used to create a common underForestService personnel weredistribplace);disturbance anddestrnction of wildlife. standing of thefirerecovery situation. utedthroughoutthe roontsothat at Whenparticipants--both citizens and leastonewasin eachgronp. The "best" and "worst" futures exThe discussion then moved from agency personnel--arrived at theissue ercise works much like other visionpresentation evenings, theyweregiven concernsto specificimprovements. blank cards and asked to write down ing processes to engagethe particitheirbestandworstimaginable futures pantsin thinkingabontthosevalues tbr the Wenatchee National Forest's that they hopeto restoreor sustain, burned areas.Workshopassistants aswellasthoseoutcomes theywould transferred these "bests" and "worsts" preferto avoid. to newsprint paperanddisplayed them A second methodforcreating a colonwallsforallparticipants tosee.This lectiveunderstanding of fire recovery activitydemonstrated that mostpeo- wasto build"situation maps"(alsoreple'sinterests in thefirerecovery situa- ferredto as"mindmaps"or "cognitive tion arefar morecompatible thanei- maps") of theprocess. The purpose of thertheirpriorexperience or expecta- such an exercise is to create a visual tionsmayhaveindicated. representation or "richpicture"(WilCertainly thereweresomestatements son and Morren 1990) of the fire re6 August1996 Based on their identified concerns and interests, participants generated ideas that they considered to be desirable and feasibleimprovements to current firerecovery management. Theydevelopedimprovements individually and subsequently discnssed themin pairs andlargergroups. Participants engaged in somepreliminary debateaboutthe desirability andfeasibility of improvemerits,althoughtheyprimarilytalked abouttheneedfor,anddetailsof, proposedimprovements. fuelsreduction,reforestation, public the Wenatchee National Forest chose to safety, andinnovative forestproducts. divideits fire recovery planninginto CL discrete CL workshops producednumerous The rangerdistrictthatembraced geographic areas, andprepare statements of concerns/interests and (EA) for mostenthusiastically organized theim- EnvironmentalAssessments more than 100 potentialimprove- provements fromtheirworkshops into eacharea.Eachof thefourrangerdisbythefirechose different mentsregarding management of the themesand developedsubsequent trictsaffected fire recoverysituation.These con- NEPA alternatives based on them. publicinvolvement strategies oncethe cerns/interests andimprovements were draftEAshadbeenreleased forpublic Colcomment. Onlyonedistrict,theLeavreviewed by theForestService aspart Action 4--NEPA-Related chose to useCL workshops to ofactualfirerecovery project planning. laborative Learning Workshops enworth, Thevarious firerecovery ID teams deThe proposed projectsdeveloped receive publiccomment at thispoint. veloped specific short-andlong-term through alternative projects forrestoring theCL process weresubject to Various projects--which emphasized trailreha- publicreviewandcomment pursuant foresthealthwerethe focalpointof bd•tation,sensitive plantprotection, to NEPA requirements, albeitnot in theseworkshops--participants .were wddlifehabitatrestoration, salvage, thetypicalmanner. The leadership of askedto scrutinize theman.dsuggest Action3--ID TeamPlanning The collaborative discussionsin the Collaborative Learning Defined Collaborative learning(CL) isa frameworkdesigned for natural resourcepolicydecisionmaking andpublicinvolvement m policydiscussions. AstableI demonstrates, it isa hybridof work in two areasof mediationandnegotiation: softsystems methodology(SSM) and alternativedispute resolution (ADR) (DanielsandWalker 1995).Thekeynotionsthat define collaborative learningare: ß redefining the taskat handnot assolving a problemor resolving a conflictbut asimproving a situation; ßviewingthe situationasa set of interrelatedsystems; ß definingimprovement asdesirableandfeasiblechange; ßfocusing on concerns andinterestsratherthanpositions; ß encouraging interrelatedsystemsthinkingrather than hnearthinking; ß recognizing that considerable learning--aboutscience, menttaskAs FloodandJackson (I 99 I) observe, SSM"isdoubly systemicsinceit promotesa systemiclearningprocess, orchestrating differentappreciations of the situation, whichis never-ending, andit alsointroducessystemsmodelsas part of that learningprocess. The systemiclearningprocessaims to createa temporarilysharedculturein whichconflictscan be accommodated sothat actioncanbetaken"(p. 177-78). From ADR: Values and Strategic Behaviors While CL'semphasison learningand systemsthinking comesfrom SSM,that areaof theorydoesnot dealwellwith valuedifferences andstrategicbehaviors suchasnegotiation; the ADR areasof mediationand negotiationdo.They also serveasa secondfoundationfor collaborativelearning.Mediation,theintervention of an impartialthird partyintoa dis- •ssues,and value differences--will have to occur before im- pute,dealswellwith significant valuedifferences (Carpenter provementsare implemented; and ßfeaturingcommunication andnegotiation interactionas the meansthroughwhichlearningandprogress occur. and Kennedy1988)."Valuedisputes," Moore observes,"are extremelydifficultto resolvewhere there is no consensus on appropriatebehavioror ultimategoals"(I 988, p. 256). The parties'strategicbehaviorsare addressed by incorporatingmethodsto promotecollaborative, integrativenegotiation (Gray 1989;Lewickiet al. 1994). From SSM: Learning and SystemsThinking The originsof CL are in soft systemsmethodology. Soft systemsis an application of theoreticalwork in systemsand experientiallearning(Checklandand Scholes1990;Wilson andMorren 1990),whichstresses that learningandthinking systemically are criticalto planning, makingdecisions about, and managingcomplex situations.These areas--systems thinkingand learning--areonesthatADR, including mediation,typically disregard or considerperipheral to the settle- Table 1. Collaborative learning as a hybrid. Elements SSM ADR Promoteslearning Emphasizessystemsthinking Dealswithvaluedifferences Handlesstrategicbehaviors High High Low Low Low Low High High Collaborative Learning and Communication SuccessfulCL processessustain quality discourse, which includesconstructive discussionof ideas,collabora- rive argument,and interaction.Communicationcompetenceencompasses theseelements,providinga dimension that goesbeyondSSMandADR processes. Regardless of the settingor groupsize,CL communication competence is fostered.Collaborativelearningencourages competent communication and qualitydiscourseby implementing interaction guidelines(e.g.,"groundrules"that value diversity) and by emphasizing variousinterrelatedcommunication "skill"areas.These include:listening; questioningand clarification;feedback;modeling;socialcognition,suchas teframing;dialogue;and collaborative argument skills (Walker 1992;DanielsandWalker 1994). Journal of Forestry 7 I. Learningabout CL and the fire recoverysituation A. Issue presentations Project plans • Subsequentmeetings B. Ground rules IV.Developingand discussing improvements A. Shortand longterm B. Desirability andfeasibility II. Creatingcommonunderstanding A. Best and worst futures B. Situationmapping III. Generating themes of concern A. Tie to situationmap B. Findingcommonand divergentinterests Figure1. Collaborative learning (CL)at thefire recovery workshops. should beleftstanding forbirds. "I maydisagree withwhatyouare saying andyoumightnotagreewith me," shesaid, "but I think we should wait to seewhat [ForestServicescien- tist]RichEverettandhisgroup[the Science Team]comeup with before we makeanyjudgments" (Partridge 1995,p. 10). Interestingly enough,Gibbsand Tankeindependently approached the facilitators to commend theapproach asa useful opportunity, andto suggest thatit beemployed in moresituations. Some lessons can be learned from desirable andfeasible changes. Work- example,a columnappeared in the newsletter of the local Audubon Socishopparticipants "debated" theproboththisuseof collaborative learrang jects,andthrough theirconstructive ar- etychapter supporting limitedsalvage in firerestoration planning, aswellasin gument examined oneanother's general loggingthatwaswrittenby someone otherapplications. First,overthepast goals andspecific ideas. who, by his own admission, had ar- several years,we havefoundit more AsthedraftEAswerebeingreleased, rivedat theworkshops steadfastly op- useful to seek progress ratherthana full thesalvage harvests ontheWenatchee posed to anysalvage. Otherbehaviors, solution. Solutionconnotes everyone became shielded frommostlegalchal- however, indicate justhowdurable po- beingsatisfied, everyissuebeingrelengebecause of sufficiency language sitionalpoliticscanbe.Anotherwork- solved, and the matter settled for all thatwaspartof thebudgetrescissionshopparticipantsubsequently wrote time--noneof whichislikelyin many legislation. Asof thiswriting,fuels-re- anartidefora regional environmentalcases. Progress, however, isvirtually alduction treatmentson 27,000 acres magazine attributingthefiresto un- wayspossible, andincremental progress (approximately 15% of the burned usually hotweatherandarguing that canleadto valuable long-term policies area)havebeenconducted through sal- the Forest Service'sconcern with forest Second, collaborative processes arenmvagesales. A totalof 106mmbfwere health/fuels management wasmisdi- therquicknoreasy. Theymustbuilda harvested(another12 mmbf wereof- rected(Hoover1995)--eventhough foundation of trust,procedural agreeferedforsalebutdidnotsell).Equally he hadparticipated in discussions at ment, and mutual commitment that important,otherfire recovery-relatedtheCL workshops thatfocused onthe moretraditional,legalistic processes projects suchasnoxious weedtreatment interplaybetween fuels,climate,and oftenlack.But theveryelements that and prevention, fuel breakconstruc- topography in shaping firebehavior. makecollaboration challenging also tion, road obliteration, and wildlife The CL workshops engaged long- make it powerful.Earnestlyunderhabitatimprovement are underway time opponentsin discussions that taken,collaborative processes do not (Wenatchee NationalForest1996). weremoreconstructive thantypically allowexclusion of ideas orgroups. occur. Often,however, thosediffering Finally,therearesomenotions speperceptions of the situationand of cificto collaborative Evaluating theCL Project learning thathave Initialevaluations frombothagency eachotherlimitedprogress. The lg3- surprised theseauthorswith theirefandnonagency workshop participants natchee lg/brld reportedhow onedis- fectiveness. Situation improvement •sa have been favorable and constructive. agreement in a Leavenworth workshop comfortable activityfor mostparuc•Citizensfelttheywerelistened to and was handled: pants;theyunderstand its usefulness thattheirknowledge andinputwere and are able to propose improvements Participants wereencouraged to respected.Participantsvalued the The participants' abilitiesin systems getintosmallgroups anddiscuss their workshops' emphases on basiclearnthinkingcontinually exceeded expectaideaswithpeoplewhomayhavedif- ing, constructive communication, and generation ofspecific management improvements. Citizensappreciated the opportunityto interactindividually andin groups withForest Service personnel, andForestService employees havewelcomed theopportunity toparticipatein CL workshops ascitizens. Someunexpectedly positive results alsooccurred fromtheworkshops. For 8 August1996 feringviews.Longtime Leavenworth loggerGrantGibbssaidonethinghe would most like to see as a result of thefireswasmorelogging of trees-especially the burnedtrees--andthe removal of debris from the forest floor. Acrossthe table,Liz Tanke,a member tions, and suchactivitiesbroaden their graspof the situation.But whilewe wouldhopethatrelationships among thevarious parties in sucha collaborative situation improve, the only marked results to date have been •n- paign,listenedintently.Afterwards, creased appreciation for theeffortsof ForestService personnel. A consider- sheaskedGibbsmoreabouthisideas, able measure of distrust between but said she felt that more dead trees groups andstrategic behavior persists of the Western Ancient Forest Cam- Theattitudes andinter-group confl•ctsthat characterize publicland management todaytook decades to form, and it will take more than a few meetings to chipawayat thosepositions. Collaborativelearning,and other processes like it, shouldbe v•ewed asincremental steps in thatdirecuon,not a freshwind blowing across thelandthatwillsweep awayall of the hardball tacticswe have seen in recentyears.Whetheroneis satisfied w•ththislevelofaccomplishment isan •nd•vidual reaction, of course.Given the contentious situations in which collaborative learninghas beenapphed,theauthors haveviewed theWenatchee effortasgenerating progress in a sound direction. It certainly created a series of forumsin whichthegapsbetween citizensand scientists,and be- tweenagencies and interestgroups, couldbeginto bebridged. ,u. Literature Cited CARPENTER, S.,andW.J.D. KENNEDY. 1988.Man- aging publicdisputes: A practical guidetohandltngconflict andreaching agreements. SanFran- Unattended Environmental Monitoring MadeEasy/ Constant monitoring ofrelative humidityand temperaturein soiland air isa vitalcomponentof any tree growthandphysiology research project. That'swhyStowAwayTM Data Loggersarea must. Economical, reusableand compact,they allowyou to accuratelycollectdata in thefield whileworkingon otherprojects.Plus,youcan programloggingintervals,retrievecollecteddata, graphresults,and downloadcaptureddata to a wide varietyof standardspreadsheet programswhenusingthededicated LogBooWSoftwareonyourPCorMacintoshcomputer. TofindoutmoreabouttheStowAway TM DataLoggers oranyof the professional productswecarry,ca//ourCatalogRequestDepartment and askforyourFREEcopyof Catalog47. It'sournewestcatalog featuring560 full-colorpagesof everything you wantand morel. cisco: Jossey-Bass. CHœCr, t>a•D,P.,andJ.SCHOLœS. 1990.Softsystems methodology inaction. NewYork:JohnWiley& CATALOG Sons. (800) DALE,A.E, andM.B. LANE.1995.Strategic perspectives analysis: A procedure forparticipatory and politicalimpactassessment. Society and Natural Resources 7:253-67 DANIELS, S.E.,andG.B.WALKER. 1995.Searching foreffective natural resources policy: Thespecial challenges ofecosystem management. In EcosystemManagement ofNaturalResources in theIntermountain V&st, ed.EH. Wagner. Logan,UT: UtahStateUniversity, Collegeof NaturalRe- REQUEST 360-7788 Fores. Jl• ......... M O R •05 W• E T •nkin LINE H A $•r• N T H E N A M E ßJ•½k•on, •i%i%ippi •0• I M P L I E • S ß/800) •47-$•8 03696 sources. --. 1996.Collaborative learning: Improving publicdeliberation in ecosystem-based management.Environmental Impact Assessment Review. In press. DIEMER,J.A., and R.C. AtVA•,EZ.1995. Sustain- ablecommunity, sustainable forestry: A participatorymodel. Journal ofForestry 93(11):1O-14. FISHER, R., andW.URY.1991.Getting toyes.2nd ed NewYork:Penguin. FLOOD,R.L., and M.C. JACKSON. 1991. Creative D.M. Saunders. 1994.Negotiation. 2nded.Burr WILSON, K., andG. MORREN. 1990.Systems apRidge,IL: Irwin. proaches •r improvements in agriculture andreMOORI•, C. 1986.Themediation process. SanFransource management. NewYork:MacMillan. cisco: Jossey-Bass. PARTRIDGE, M. 1995.Environmentalists, loggers ABOUT THE AUTHORS talkfire-recovery. lY&natchee lY•r/d10 (Jan.15). WALKER, G.B. 1992.Towarda theoryof conflict communication competence. Paperpresented at Steven E. Danielsisassociate proj•ssor, problemsolving.' •tal systems intervention. the International Association for Conflict ManChichester, UK:JohnWiley& Sons. agement Conference, June,Minneapolis, MN. FREIDMANN, J. 1973.Retracking America: A theory WALKER,G.B., and S.E. DANIELS.1994. Coflaboratirelearning andthemanagement of natural oftransactive planning. GardenCity,NY:Anchor Press. GRAY,B. 1989. Collaborating. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. HOOVER, M. 1995.Weatherbig causeof Wenatchee forestfires.Columbiana 5(2):32. LEWICK1, R.L., J.A. LITTERER, J.W. MINTON,and resource disputes. Paperpresented at theannual meeting of theRuralSociological Society, August12, Portland,OR. WENATCHEE NATIONAL FOREST. 1994.Fireinj3rmarionsheet.Wenatchee,WA: WenatcheeNational Forest. Department of ForestResources, and Gregg B. •lker isassociate proj•ssor and chair,Department ofSpeech Communication, Oregon StateUniversity, Corvallis 97331; Matthew S. Carroll is assistant proj•ssor andKeithA. Blatner isproj•ssor, Department ofNatural Resource Sciences, •shingtonStateUniversity, Pullman. Journalof Forestry 9