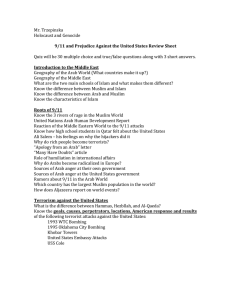

ARAB OPINION ON AMERICAN POLICIES, VALUES AND PEOPLE JOINT HEARING

advertisement