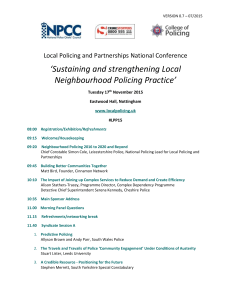

THE NORTHERN IRELAND PEACE PROCESS: POLICING ADVANCES AND REMAINING CHALLENGES JOINT HEARING

advertisement