( CURRENT ISSUES IN U.S. REFUGEE PROTECTION AND RESETTLEMENT HEARING

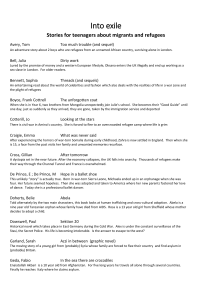

advertisement