SOMALIA: EXPANDING CRISIS IN THE HORN OF AFRICA JOINT HEARING

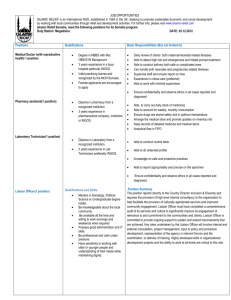

advertisement