NOT FOR PUBLICATION UNTIL RELEASED BY SENATE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE STATEMENT OF

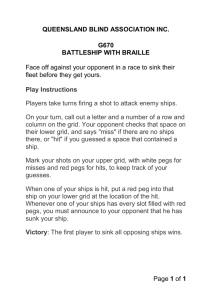

advertisement