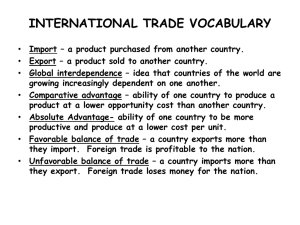

( U.S. TRADE AGREEMENTS WITH LATIN AMERICA HEARING COMMITTEE ON

advertisement