Negotiating the Path of Abraham Working Paper

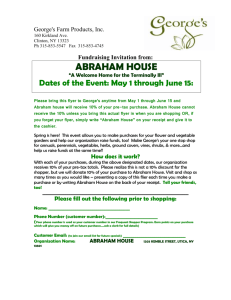

advertisement