WHISTLEBLOWER PROTECTION DOD Needs to Enhance Oversight of

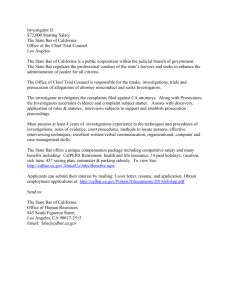

advertisement