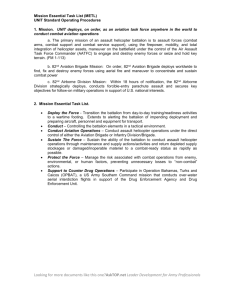

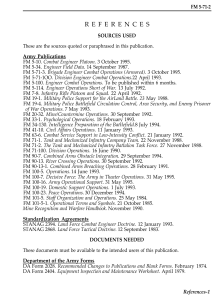

Third Infantry Division (Mechanized) After Action Report Operation IRAQI FREEDOM

advertisement