Report on the Protection of Civilians in the

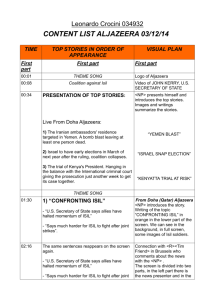

advertisement