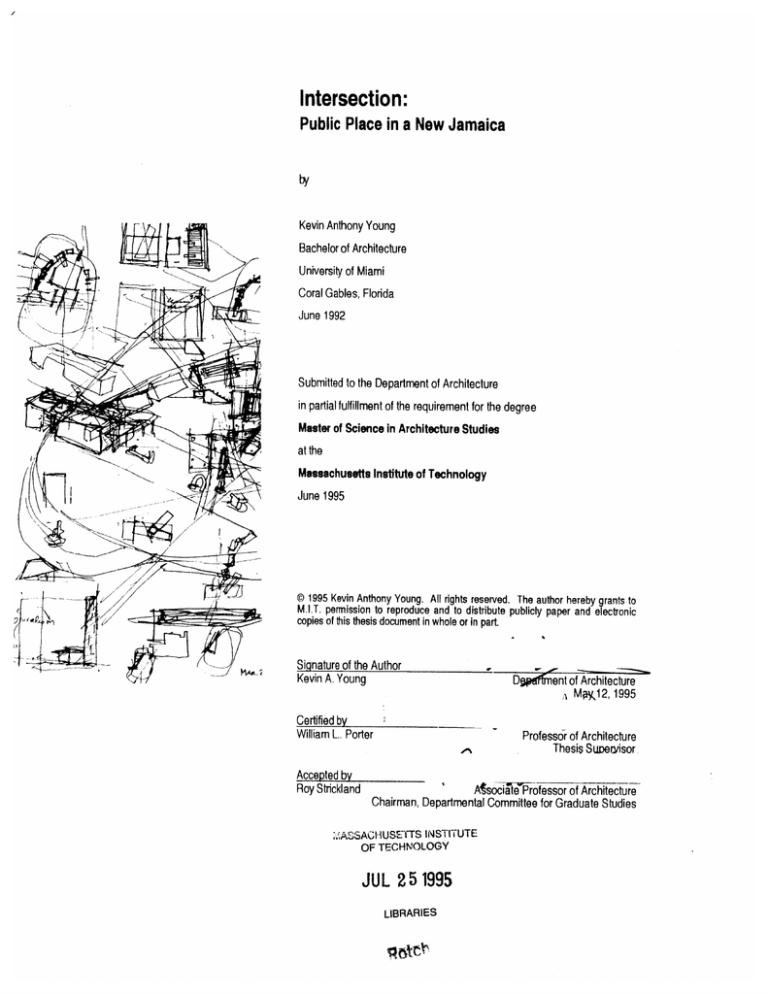

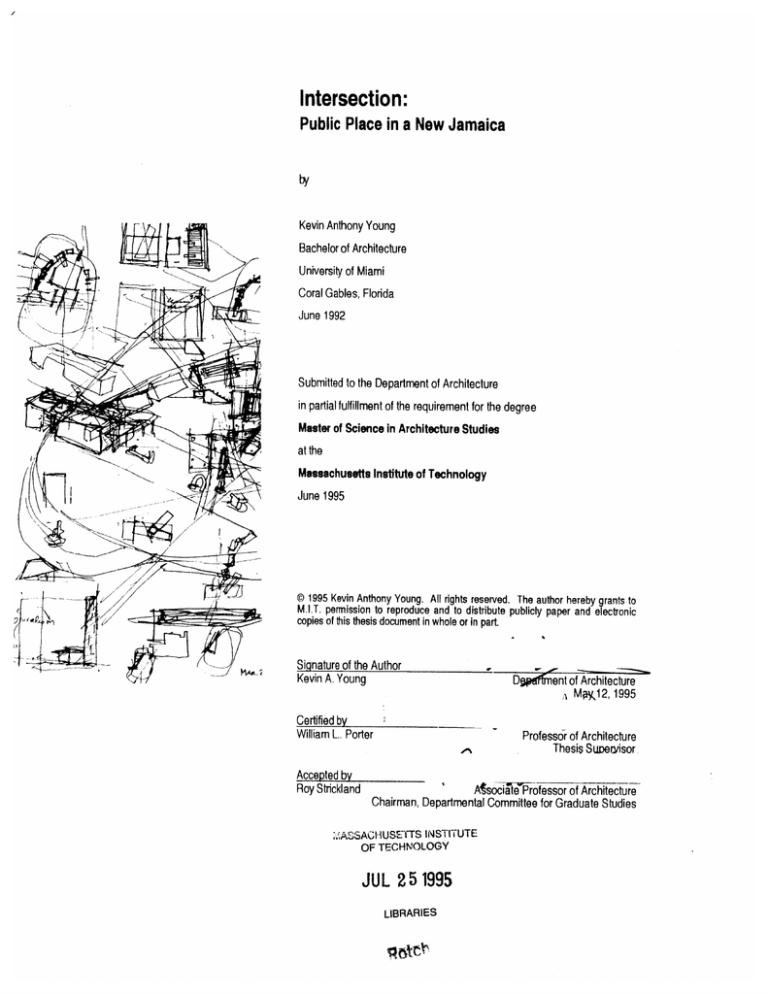

Intersection:

Public Place in a New Jamaica

by

Kevin Anthony Young

Bachelor of Architecture

University of Miami

Coral Gables, Florida

June 1992

Submitted to the Department of Architecture

in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree

Master of Science in Architecture Studies

at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

June 1995

@ 1995 Kevin Anthony Young. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to

M.I.T. permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic

copies of this thesis document in whole or in part.

Siqnature of the Author

Kevin A.Young

Certified byWilliam L. Porter

Accepted by

Roy Strickland

Dgsirent of Architecture

, My12, 1995

Professor of Architecture

Thesis Superyisor

AfsocIiateProfessor of Architecture

Chairman, Departmental Committee for Graduate Studies

;.ASSACH-JUSEFTS INSTITUTE

OF TECHNOLOGY

JUL 251995

LIBRARIES

MITLibraries

Document Services

Room 14-0551

77 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02139

Ph: 617.253.2800

Email: docs@mit.edu

http://Iibraries.mit.edu/docs

DISCLAIMER OF QUALITY

Due to the condition of the original material, there are unavoidable

flaws in this reproduction. We have made every effort possible to

provide you with the best copy available. If you are dissatisfied with

this product and find it unusable, please contact Document Services as

soon as possible.

Thank you.

The images contained in this document are of

the best quality available.

2

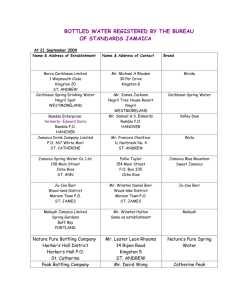

Intersection:

Public Place in a New Jamaica

Submitted to the Department of Architecture

in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree

Master of Science inArchitecture Studies

at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

June 1995

by

Kevin Anthony Young

Abstract

Jamaica, a microcosm of the Caribbean and the developing world, is heir

to an ambivalent legacy. While she benefits from a unique cultural tradition

brought inpart through colonialism, she suffers from the nihilistic tendency

to imitate colonial socio-economic practices. The society thus becomes

more and more polarized, and is poorer for it.

The condition is a paradigm for architecture and urbanism. The city

stratifies itself into political and economic zones, allowing for its own

demise through the lack of communication and cross-fertilization.

In anticipation of the city's continued explosion, the thesis explores the

possibility of a new public place at which the separate social groups may

converge. It will facilitate the accessibility of Jamaicans to their own

diverse population, and foster self-pride as they recall and celebrate their

traditions, accomplishments and ambitions.

The program therefore consists of public facilities which bring Jamaican

cultural traditions into relationship with each other. The complex is

intended to be a multi- purpose sports/festival ground. Its focus will be a

Museum of National Heritage.

The site is National Heroes' Park, a 68 -acre oval which sits at the

boundary of the parishes of Kingston and St. Andrew and marks the

entrance to the old city of Kingston, capital of Jamaica. It originated as a

horse-racing course in the 19th century but has been transformed

successively over the years. Part of it is now dedicated as a shrine to

Jamaica's National Heroes - the seven men and woman who were

deemed to be instrumental in the building of the nation.

Thesis Supervisor:

Title:

William L. Porter

Norman and Muriel B.Leventhal

Professor of Architecture and Planning

Thesis Readers:

Ellen Dunham-Jones

Attilio Petruciolli

3

4

Acknowledgements

Big up to the following:

Granny B,for asking one evening, "Why doesn't somebody

propose something for Heroes' Park?";

Bill Porter, for his wise and patient guidance, and a refreshing dose of

coolness;

Ellen Dunham-Jones and Attilio Petruciolli, for their timely and thoughtful

criticisms;

Juan Calvo, for his insight when I was, thinking back, in grave need of

some;

Jihad, for the garage space, the good advice in general, and at times, a

swift kick in the pants;

Bob, for the music;

Errol Alberga jr., for introducing me to a discipline, and then watching

with keen interest as I learned;

Aunt, for making sure I ate properly those first years away;

Rocky, for being my first fan and cheerleader;

Mom and Dad, whose love for, support of, and belief in me has been

selfless and unchanging. Though no words could express my gratitude, I

rest in the knowledge that now, as always, you share inthe pride and

relief of this accomplishment.

Dee, my love and my sunshine, for making the future worth every minute

of this effort.

God, for everything ...

5

6

Contents

Abstract

3

Acknowledgements

5

Table of Contents

7

part I. SITE ( The Physical and Social Context)

1.1 Thoughts on A Mixed Culture

9

1.2 The Park as Public Place

27

part 1\.PROJECT

2.1 The Space of Pluralism

37

2.2 Urban Moves, or One -One Cocoa...

41

2.3 Conclusion

61

Bibliography

65

Illustration Credits

67

7

f 1.1.1

8

Part of Mural, University of the West Indies, Mona.

. SITE

"The night starts to fade,

but the moonlight lingers on;

There are wonders for everyone!

The stars shine so bright,

but they're fading after dawn;

There is magic in Kingston town..."

Clancy Eccles and Kendrick Patrick

Thoughts on A Mixed Culture

Jamaica is the quintessential pluralist* society, and Kingston, the pluralist

city. This has to do with the fact that West Indian colonialism was a

unique project: When Great Britain pushed into the New World in the 17th

and 18th centuries, she may have found fertile lands, but certainly no

trace of an indigenous culture. The extermination of the Caribbean

Indians by the Spanish, and their own subsequent expulsion, had seen to

it that there was no reference, no existing foundations (as there would be

in India , or in Africa and the Middle East) upon which Britannia could

propagate her aspirations of empire. Into this cultural vacuum came two

distinct groups: Expatriates from the motherland; and Africans inshackles,

bound to a life of slavery. They were later joined by Chinese and Indian

labourers in the 19th century, as well as Semitic peoples in search of

fortune inthe prosperous economic climate of those years. Their various

pluralism (Random House): a theory that there is more than one basic substance

or principle.

9

jij

\ \

1W.

I

N.

\

ILI I.

1)1.

I.-

I\INL~' 1O\

-;

A.1..a,

I'

2 U1'JWiLiWfW

RED

UG190Dooooootpoeaco1

LiJ LJJLJ LLJ

BIG MIXUP:Ilhis is the earliest knon

i

I

I LUW JJLJ

'

, ut

tiPlan uas driawn by John Goffe. Col. Christian 'Lilly.wa

the City wvassettled in 1703. Note No. 18 - P-rinacx Street Ins len co (ple

National Library PlIto.

Princss Street.

.

f 1.1.2

f 1.1.3

10

I

/0..

,

,

/.

.

BeHin's Map of Kingston, c.1760.

Parade Square, c.1990.

/

i

I)

,.'

.114

I.

'

hah

cultures, (and their blood inmany cases) merged inextricably over time to

create a diverse society of amicable, if not always co-operative, accord.

This has had decisive implications for urban development. B.W. Higman

has observed that: "In the Jamaica of the 18th and 19th centuries, there

were two competing attitudes to space and its organization. One, derived

from the European frame of mind, sought to create a rigidly ordered,

geometric landscape. The other, with its roots in Africa, placed a greater

value on fluid natural lines"1 . In fact neither attitude could materialize in a

pure form. The European model, for all its 'legitimate' power, could not

overcome the will of the mass slave population, and indeed the contour of

the land, in the shaping of the public realm. The African mentality by

comparison, could not fully withstand the cultural assault and socioeconomic privations exacted upon it by colonial domination. The colonist

and the conquered were forced to adapt to the new environment.

Bellin's 1760 map of Kingston (planned by John Goffe in 1692) reveals

the first futile attempt at idealism. An account by Johnson reads: "The

town was drawn up as a parallelogram, one mile long from Port Royal

Street to North Street, and half mile wide from East to West Streets. The

main street (King) ran South to North in the dead centre, and it was

intersected dead centre also by Queen Street." 2 Where both "royal

streets" intersected was reserved for a four-acre square to be used as a

military camp (hence the name 'Parade Square'). The tabula rasa context

influenced the translation of the theoretical Renaissance utopia - then in

use in Europe for the construction of several 'new towns' - to Caribbean

1In Jamaica Surveyed, p291.

2

Anthony Johnson, Kingston: Portrait of ACity, p47.

11

11.1.4

nwf~ltF'

View of Vitry-Le-Francois, France, 1634.

T1

iTkIIOF IANooN

DE giF AS.1T )TANo

I 1.1.5

12

Plan of Londonderry, Northern Ireland, 1622.

shores 3 . In this, Kingston would briefly resemble American colonial towns

such as Pittsburgh and Savannah. In fairness, this was not a totally

arbitrary geometric exercise: the City, after all existed primarily for the

defense of its inhabitants, who were subject to the horrors of frequent

pillage from competing colonial powers. It was thus practical to lay out its

borders more or less equidistant from a central gathering area, whose

primary function was to house the military battalions charged with its

defense. Also, the city's North-South orientation allowed the flow of

prevailing winds to cool the hot, dusty Liguanea Plain*.

The imposed uniformity of the plan nevertheless begins to ridicule its own

rigidity. The main streets must contort in order to connect to pre-existing

routes to and from the city. Their dominance is compromised. What

Rowe calls "conditions of confusion and picturesque" - in the case of

Kingston, river and stream beds later built as drainage ditches and gullies

- create their own irrational order between the grid 4 .

Outside the city, early plantation maps showed a similar confounding of

this attempted regimentation. The mainstay of the colonial economy was

the production of primary products (mainly sugar) for export to the

metropole, and the majority of Jamaicans lived and worked within this

spatial context. The landscape was thus, for the most part, partitioned by

the borders of such entities, and in fact, Kingston's future expansion would

be dependent on the atrophy of the sugar plantation. It is here that two

trains of thought vis a vis space planning may be observed. The immense

3

John Reps, The Making of Urban America, p12.

The gently sloping 150,000 acre parcel on which Kingston is built: - Johnson

purports the name to have derived from 'iguana', the large reptilian which would

have been found inabundance there at the time of colonization.

4

Colin Rowe, Collage City, p107.

13

L

iAn-ArAwwiz

A.

AsAAAaltai-ArAL

AS ALE,-1*

St

ALL

4s a

AaAL

L 4ith

A.

ALALAttALA S LA

44

i iA

ALA

AAsaAAALAaaAAS

A& I

&A.

a

i\&A

I

LALA

LAX

LaL

ALAL

& & AAL

AL9

Au

~

1~.

~

~

ALIAALAA

:A&

a

A

~

7 ~ JA

aa

a

$4 aa LL

WA

A

r r~

A

4,

.Ifr~

a A A aa AA

a

L

t A Ad 'T

&& A

A

t fL

A A A -Ak

AgLA&LALLi I j

A

t L #'

A

4k

AL

A'AX

& A

A

A

A

IA

LA

A

A A-

lap,_aba

4

-

-

SA

At A

A

SSALaDa

AaAt

4..

A

A

aA AAL SA A

A L AAIa

$k:AAAaA

a

a

aakka

LL

ALL

o.

asiia.

AALLeuA

AA

A

A

Ls AAL-tA

A.AAL A~

A A

LALAuL

AALAIA

aatALA

&I,#

mam

I

eAgLa-A A

LA

L Aa At

A L4AILL

AL~'

titI

w4 f.ff&

i

A

4I

A

L

A

BA a

ALA IL

AL.nsL

6as Ls..):

A

I

A

A A LAA A

A LALAA

A

A

A.'i

AL A .

-A-

-

-A S

~

..

Ak

<J

f 1.1.6

Laborie's Ideal Plan for a Coffee Plantation, 1798.

11.1.7

f 1.1.8

Plan of Lucky Valley Estate, Clarendon, 1816.

f 1.1.9 View of the 'Free Village' of Sligoville, St. Catherine, 1843.

14

Plan of Belvedere Estate, St. Thomas, 1800

grounds were often laid out ina more or less triangular fashion, with great

house, sugar-mills and works, and slave quarters occupying the three

apices. While the great house functions adhered strictly to a precise

geometric ordering, the slave village was patterned on a different

conception. From the main road reaching the rest of the property, the

village grew off in multiple branches to either side, in every which way

describable, creating a motley composition on the land. Higman recounts

an 18th century description: "Inever witnessed on the stage a scene so

picturesque as a Negro village.. Each house is surrounded by a separate

garden, and the whole is intersected by lanes, bordered with all kinds of

sweet-smelling and flowering plants". Significantly, the writer, a planter

contemplating his own operations, made note of the vitality of his slaves'

lifestyle, in spite of their spartan accommodations. No doubt he was privy

to the workers' assertion of independence and individual expression, in

reaction to the authoritarianism of plantation life. Paradoxically, the

arrangement was not far removed from the British tendency to plan

gardens in Romantic, fluid curves, as an escape from the hardness of

urbanity. This place of harmonious conflict where, as Higman says, "myth

and reality converged", was the literal and symbolic foundation of the

future city.

The unplanned growth of Kingston was accelerated by the abolition of the

slave trade and the subsequent downfall of sugar production, the

plantocracy, and sugar estates. But while it was economic necessity

which drove planters to subdivide larger and larger sections of their

properties for purchase by Kingstonians, the fragmentation of the urban

fabric continued a trend of land privatization begun even before

emancipation in 1838. Alook at Lowndes's map (f 1.1.10) already shows

15

PondR-

-ah

-4

S11.10

1. A-j

Lowndes's Map of Kingston and Surroundings, c.1770.

16

6'A'

1.1.11

16

Plan of Hampton Court Estate Subdivision, St .Thomas, 1847.

the grid of Kingston surrounded by pockets of small holdings called 'pens'.

It was these semi-urban havens to which the city's merchants retired in

the evenings to escape the hot and sometimes squalid atmosphere of the

city centre, or which the rural planter kept for his lengthy stays during the

theater season. Furthermore, a new intermediate class had entered the

picture: Their ranks drew not only from the illicit unions between master

and slave, but from the progressive hybridization of the population due to

the infiltration of multiple ethnic groups described above. The new

bourgeoisie - free, in most cases educated - possessed too the wherewith-all and the desire to live outside of the city in its more comfortable

foothills. Add to this a burgeoning ex-slave population, anxious to forge its

own destiny in the new society, which preferred to live on subsistence

farms in locations far and near to the city, and you have an urbanism

which could astound even the most knowledgeable analyst, or seasoned

traveler. On this, Higman is articulate: "...The end result was a complex

creole mosaic, the Jamaican landscape being composed of intermixed

large and small holdings, some laid out on strict geometric principles and

others following the natural contour of the land. Thus the landscape

mirrored the structure and constituents of the society".

Kingston would eventually creep forward to engulf an area of 192 square

miles, an astonishing 96 times its original area+ . The grid of the old city

occupies only a small portion of this sprawl, leaving one to assume the

presence of a secondary ordering device implicit in the 'plan'. Studying

the growth pattern of Kingston (f 1.1.12-13) shows more clearly the

presence of demographic and economic forces run amok. There is no

+St.Andrew isthe parish immediately bordering Kingston to the North, and

together with it forms the corporate metropolis of Kingston &StAndrew.

17

S

SUBURBS

SON W CARDNl :4C

1889

f 1.1.12

18

-

Kingston and its Suburbs, 1889.

f 1.1.13

Central Kingston, 1972.

mu"

apparent uniformity in direction or layout as multiple streets burst out of

the grid to eat up the landscape. This is not surprising, since Goffe's plan

was designed to have had limited dimensions, and did not lend itself to

expansion beyond a certain point. The Parade can no longer be

HF

considered a centre inthe classic sense, since it retains none of its former

hierarchical dominance, It is more accurate to say that Kingston evolved

pastorally, for the main streets go forth, almost willfully, negotiafing hills

and valleys along the way. They meet each other at various points,

carving public space through time. The city has become one of multiple

nuclei. The order is revealed: It is not singular, but plural.

In the living net of roadways cast over the landscape, zones of intensity

are created at the knot - at the intersection. The traveler must orient

himself at the crossroads. It is only at these moments that he pauses for

rest, reflection (and a drink of rum) before hurrying slap-dash toward

another section of town. The road junction is thick with historical

(GO9D5

association, is imageable in the minds eye. The junction represents the

character of that quarter for which it is the focus. In Kingston there are

several such nodes, with names as colourful as the people who pass

through them: Parade, Cross Roads, Half-Way-Tree, Matilda's Corner,

Papine, for example. Some are mile markers, reminding the traveler of

the distance he has yet to cover; some are the occasion to saunter

through a garden of tropical flowers; some celebrate the transformaion of

the land itself, as at Papine, where the long Hope Road comes to rest

r F -y

TI

E

before another takes its place, shooting up into the Blue Mountains. Their

'boundaries' - their architecture -are often accidental, occurring at the

points of least resistance to the crossing roads. They are built up,

f 1.1.14

Figure-Ground Plans of Three Intersections.

19

1

cm

zof

0

(13

cn

I

(=

0

$-

(A

C

NcN

adjusted, and decorated anonymously over time. They are places of many

and varied - in short, plural- encounters.

Modern Kingston, the place of myth and reality, is also plural in the sense

that it simultaneously unites and divides. In analysis, author Katrin Norris

is less sympathetic than Higman: "Jamaica is two nations , sharing the

same space, but hardly touching each other", she wrtes 5 . For her, social

polarization, begun in colonialism, and seen on the plantation, has

survived through independence. The classes do not "converge" at all. She

identifies the irony of a unified propaganda: that as the new nation seeks

to assert its individuality through profession of a unique hybrid society, it

allows itself to duplicate the socio-economic practices of its former

overlords, which is separatist by design. "The more pleasant frontages of

the city", she continues, "seem to hide a mass of humanity living in dense

conditions of squalor". One need not view Kingston through a microscope

before realizing this truth. In downtown, modern towers of shimmering

plate glass stand in stark contrast to the decaying tenements around its

base; well-kept suburban homes seem like hotels and palaces compared

with the zinc-aluminium shantys clustered along the route; BMW's whizz

by slow-moving donkey carts on a daily basis.

They are all symptoms of what I will call 'Third World' modernism.

Marshall Berman explains that developing countries build modernity upon

a "fantasy" of modernism which is observed in advanced nations, rather

than on modern realities internal to their own societies 6 . This entails,

among other things, the observance of norms of comfort and leisure

practiced by the middle classes inAmerica, and not far removed from the

5

1nJamaica - The Search For an Identity, p42.

1n All That isSolid Melts Into Air, p232.

6

21

f 1.1.17

House, Kingston.

f 1.1.18

22

f 1.1.19 Jamaica's Coat-Of-Arms, expressing the National Motto.

House, Kingston.

aristocratic lifestyles of the former planter class in the colonies. Civic life

isthrust out infavour of private pursuits. Community action is sacdficed to

individual gain. Citizens lose identification with each other and thus with

their common destiny. The shopping malls and plazas littering Kingston

are fast becoming the space for gathering, but they alone cannot serve the

public life, since they are places for consumption, and as such

automatically eliminates one income group from the picture. They are the

embodiment of an international, non-specific pattern of behaviour, having

little to do with regional or local culture. In Jamaica the schism of caste

distinction is immediately apparent and pervasive, and it is tragic, since as

a developing nation, she can scarcely afford for this to happen. The

nation, the city, may as well grind to a halt if it is willing to always separate

itself.

By that same token however, Kingston has proved both the appraisals of

Higman and Norris, and, in Berman's own words, shown itself to be

uniquely modern: He later marvels that the "truncated" modernism of

underdevelopment, because of the extreme social, political, and

spiritual/religious pressures under which it grows infuse it with an

"incandescence" which the relaxed modernism of the First World "can

rarely hope to match". This approaches the comment of a Jamaican

movie director: "The Jamaican consciousness is just burning out of sight.

Its history is African. Its culture is European. Its politics, Third World.

We're producing a totally new breed of human being" 7 . The new

Jamaicans must be motivated to put this energy into collective work,

realizing that the advancement of the society depends on individual

discipline and effort, and not the other way around. They must again be

7

Quoted inthe APA guide book, Jamaica, p 79.

23

S1.1.20

King Street, Kingstn, today.

f 1.1.21

24

Church and Vendors, Kingston.

made proud of their history, for this reminds them that there is something

to lose in the tidal wave of internationalism - it gives them something

which is worth fighting for. To reiterate, the aspiration to modernity and

international standards is itself ambitious and forward-thinking, but

becomes detrimental to the developing country when it involves a sacrifice

of regional culture and resources. Or, in the lyrics of another Bob Marley

tune, which, in true form of Rastafarian* egotism, solicits a defiant selfpride: "..Children, get your culture, and don't stay there and jester!..".

Show them this reference point, this common ground. It is the innate

knowledge of each others share in the Jamaican experience, which has

kept them together, and will push them forward.

Finally, The future of Kingston, the "collage city", rests in Colin Rowe's

presentation of the new city as an amalgamation of traditional and modern

planning. "We have two models", he writes. "Wishing to surrender

neither, we wish to qualify both...Allow for the joint existence of the overtly

planned and the genuinely unplanned, of the set-piece and the accident,

of the public and the private, of the state and the individual. It is a

condition of alerted equilibrium which is envisaged.. .Cross-breeding,

assimilation, challenge, imposition, superimposition, conciliation: these

might be given any number of names..."

I prefer to call it...intersection.

*Millenial cult, having its roots inJamaica, which professes the divinity of H.I.M.

Haile Selassie 1(1891-1975), last Emperor of Ethiopia. His christened name was

Ras Tafari, the Ras being a noble title roughly equivalent to Duke.

25

The shame of National Heroes Park

* Now a haven

By Gary Spaulding

-

THE National Heroes Park. Heroes

Heres

Circle. was designated

of

an

to Inter

served conted

utornothe remains

of

great contributors to the nation

but for some time now the park

has been serving a muitiplicity of

other purposes.

It has become a haven for

idlers, a home for squatters, a

playing field for youngsters, short-

for

Jrau~z~

ars~tQova

lovers and rapists

cut for pedestrians. rendezvous for

lovers and the locus for robberies

and rapes.

.

ers had to order flowers to give

some respecttbility to the place.

A few women. who said they

A number of the tombs of great

Jamaicans are In need of repairs.

the naSangster.

DonaldPrime

That

tion's ofsecond

Minister,

is

were einployed to "rake up the

place,' were doing just that; but

more than raking was

much

needed.

high on the list.

When the Gleaner visited the

park on Monday. the area was

parched and barren. When the

Little Theatre Movement honoured

Ranny Williams Saturday with a

ceremony at his tomb. the organis-

One of the workers. referring to

the tomb of Mr. Sangster, ex.

claimed -fDem ito see it waan fix

an' paint! Si. noted that the inscribed words "Prime Minister'

needed to be re-inscribed as they

Ties were loosened. the

had

f 1.2.1 Article in the Daly Glean& (Kingston)

26

P..

idlers, squatters,

laded.

inscribed words were no longer

legible and the tomb itself was a

filthy mess, with broken bottle

and other debris on itHeadstones have not .been

placed on the tombs of' Mallica

"Kapo" Reynolds, internationally

famous sculptor and fenowned revivalst: and Ken Hill, trade union,

journalist and politician, who

both died in 1989.

The front of the park has beein

cone a squatter settlement.

live. demi sleep, dem do every ting

Ist.

dey." one worker explained.

mevene,

naeInabd

day light."

Men, with what seemed to be

their 'belongings". were fast asleep

under the shade of trees when the

Gleaner ventured to that section of

the park. The worker said that the

gates to the park were closed in

the evenings but people still "scaled- the fence.'

The area that encircles the

shrines of the National Heroes is

well kept. The plints and flowers

are well tended. But who could tell

that this is the National Heroes

Park? There is no identifying sign.

The Park as Public Place

Place and space are distinguished thus: a place is a memorable location,

containing some aspect or aspects which identifies it as being unique,

separating it from its surroundings by visual or other sensual perception.

A space on the other hand, is simply an actual or implied enclosure, like

the hole in a donut, or the horizon yonder.

The Caribbean, Jamaica, Kingston, Heroes' Park, by the definition above,

are places. But the designation of 'park' is a misnomer, since it stops

short of fulfilling its purpose: to provide a place of public respite, a retreat

of sorts for the citizen to use, enjoy, and remember. For all its place-like

qualities, it fails to evoke a sense of place. Dunham-Jones goes further to

say that in the experience and apprehension of a place by humans, "..its

objective description becomes layered with multiple subjective memories

and associations through which it becomes meaningful. Sense of place is

strongest in those places which are endowed both with distinctive physical

features and with significant cultural meaning and memories".

8

It is this

quality of 'not yet being' - of not yet drawing such association - that is

fascinating about the site, because it should not be so. Furthermore, the

park as an urban element, in its isolation from the public, parallels the

condition of Jamaican society which I choose to address: that is, the rigid

demarcations of class structure and the subsequent lack of common

ground on which to meet as a people.

It should not be so because at different times, the park seemed to have

been so endowed. It marks two important boundaries in the city: one

physical, the other, socio-political. Its southern tip brushes the dense

8

From course notes, Architecture, Placeand Contemporary Culture.

27

f 1.2.2

f 1.2.3

28

View South on West Heroes' Circle.

Plan of Park Area, today.

urban fabric denoting the edge of the old city of Kingston, which is now

referred to as 'downtown'. Its northern fringe meanwhile, coincides with

the original 'dividing' line of Kingston and its suburban counterpart, the

parish of St. Andrew. While this inadequately describes the mercurial

quality of both physical entities, it is otherwise significant. To the motorist

heading south with some degree of speed on its western tangent, The

sudden expanse of the park frames his vision of old Kingston, allowing

him to experience its facade, and reminding him of the imminent

approach of its confines. To the architect in search of a narrative, The

physicality of the park presents a myriad of associations with the

urban/suburban, disadvantaged/privileged, public/private dialectic. It is an

intermediate zone, resting, as Olive Senior has written, between "the

psychologically and economically exclusive areas of 'uptown' and

'downtown'." It is not quite inside or outside the city, but a combinaton of

the two, as a front porch or verandah would be to a house. Like a

verandah, it is disappointing when one walks up to find it silent and

deserted.

It should not be so because the air around the Park once bristled with

excitement. Great crowds spilled over its edges in 1804 when it was

inaugurated as the Kingston Race Course, and every race day since. As

with so many places of memory, legends persist: of a mysterious obeah

(voodoo) woman who lived on its perimeter and could, as she fancied,

help or hurt ones chances of winning; of a con artist who once 'sold' the

race-course to an unsuspecting buffoon.

Racing was at first an annual event, but the park's prodigious acreage

offered opportunities for all manner of gatherings throughout the year.

1.2.4

View of Par* from Wolmer's Boys' School.

29

f 1.2.5

f 1.2.6

30

View of Kingston Race Course, 1804.

View of National Heroes' Park, 1994.

Circuses, fairs, and expositions could find ample room to present

themselves to the City. The removal of horse-racing to a new location in

the 1950's did not deter constant public use of the space: the park

supported the premier sports field in the Kingston area, if not the entire

island, until the National Stadium was constructed in 1961. In times of

national emergency, as after the great earthquake of 1907, it served as a

tent city for the victims rendered homeless. Beyond that, it was

transformed into a public garden and cemented within the national

consciousness when the decision was made at Independence to turn it

into a shrine for the memory of Jamaica's National Heroes.

This was in fact a watershed event in the life of the park, for,

paradoxically, with its new role as national monument came the blind

removal (the new facilities at the Stadium quickly sucked away that aspect

of the park's importance to the city) of the amenities which made it

desirable for public use. It seems as if the park was to be restored to a

state of pristine grandeur, something to be looked at rather than used.

Regardless of its many prior transformations, it had always retained a link

to the surrounding communities through popular activities, ranging from

the Sunday stroll to the giant town meeting which took place there

intermittently.

Now, following the haphazard removal of each to

specialized areas around town, the park lost much of its vibrance. In

addition, the sixties saw the ringing of the park with modem government

buildings, acquiring for it a stiffness and formality which belied its

relationship with the city, which, as we have seen from historical maps,

was in no way planned to formally connect. So, unlike the integrity of the

Mall with L'Enfants Washington, D.C., Kingston's Heroes' Park as Plaza

Major was an imagined construction. The planting of monuments to the

31

f 1.2.7

f 1.2.8

32

Monument and Facade.

Monuments Over Wall, from left Bogle and Gordon, Bustamante, Manley.

Heroes in a line at the southern sector was a weak gesture of

territorialization, and is not yet powerful enough to provoke the kind of life

envisioned by the Government and planners of the park. It became but a

national symbol, which, as is sometimes the unfortunate case with those,

a shadow of the reality for which it stands. More recenfly, the monuments

were walled off and gated for, it is often defended, their own protection.

The complete impotence of such a move is made even more poignant by

the emptiness of the sixty-five or so other acres from which the public has,

not altogether mysteriously, vanished.

However, Norberg-Schulz, pointing to the reciprocity of public place to

public life, says that public place can begin to stitch these fragments

together, to keep society bound in some coherent whole. It may be able

to accomplish for public life what the public has neglected to make happen

itself. After all, the park has resisted the developer's bulldozer and the

squatter's hut only because it remains a vague part of cultural memory,

and, just maybe, it is more sacred than people will admit. It endures, and

that says something, since so much of the old Jamaica has disappeared.

He writes: "The concept of place has two meanings: place of action, and

point of departure. Hence it represents what is known and what permits

man to depart towards a more distant goal. Only when the individual

possesses such a point, or system of points, of reference, he may act in a

meaningful way" 9 .

The fact is that here is the opportune place for 'place'in Jamaica. Heroes

Park is such a point of reference, needing only to be intensified to be

perceived by the individual and collectively, by the nation. The layers of

9

Christian Norberg -Schulz, Architecture, Meaning and Place, p.30.

33

CA,

8

9a

CO,

co

history, the making of a culture -"what is known" - now dormant, must be

excavated. Its experience, and with it the Jamaican milieu, must be

remembered. To be the "place of action and departure" for the people, it

must bridge the social impasse and be accessible to all. Its use through

the years by Jamaicans legitimizes its continued function as public space;

its presence, the grim reminder of the folly of segregation. Its unkempt

grasses and shade trees, oblivious to the sadness of the park, still burst in

colour after the rainy season, and beckon to the weary traveler. The

proud monuments - to Bustamante and the Heroes of 1865 - peek out

from their concrete prison, giving all a pause; perhaps the sudden hint of

exhilaration which comes with the realization of belonging to a young

nation with so much promise; and maybe the wistful awareness of the

work left undone to achieve it.

And, if at long last one enters its domain, to perhaps sit for a while and

look around, the city, the formidable mountain range which is the spine of

the island, the sky and sea, vehicles and people bustling to and fro in a

faint hum, are displayed like a strange and wonderful movie of

unpredictable ending.

The site, in many ways, / Jamaica, and

undoubtedly, the place for her rendevous.

35

f2.1.1

Walls- A West Kingston Street,

f 2.1.2 Courtyard - Jamaica House ( Office of the Prime Minister), St. Andrew.

I

A

f 2.1.3

36

Fence - Ministry of Agriculture, StAndrew.

i.

PROJECT

"And verily, verily, I'm saying unto the I,

I - nite oneself, and love I - manity;

'Causepuss and dog, they get together,

what's wrong with loving one another;

Puss and dog, dem get together,

what's wrong with you my brother?

Ah so Jah seh.."

Robert Nesta Marley

The Space of Pluralism

The aim therefore, is to extend, rather than contain. Kingston/St.Andrew,

the urban dynamo, has defied control since its inception, and has grown

beyond the wildest dreams (or nightmares, depending on one's outlook) of

planners and residents. The citizen's defense mechanism has been

introverted activity, closing the yards of their homes and businesses off

from public view and access with an architecture of walls, spikes and

grills. As an alternative to the false security of partitioning the city, which

produces further areas of alienation, isolation and danger, I propose an

attitude of reconciliation, compromise and continuity.

The new public place of social interaction must mediate the chaotic, not

create, if indeed it could, a rarefied area where the chaotic is non-existent.

I advocate the simultaneity of the storefront and sky-juice cart, of the

wayward goat and pedigree dog, of money- football and the Manning

37

f 2.1.4

Mobile Sound System.

f 2.1.5

Public Life I - Carnival.

f 2.1.6

38

Public Life II - Watching Cricket at Sabina Park, Kingston.

Cup.* Only this will have summarized the essence of Jamaican pluralism.

The new public place must somehow draw public life, capture its vitality

and richness in an instant, and lead it off again, to others like it elsewhere

in the city. The Park is reconsidered as a place of linkage in the existing

network, a transitory, yet memorable moment, valid only inasmuch at it

serves the impulse of movement and the necessity for access through the

city. The urban gesture then, is the purposeful articulation of the process

which has never been allowed to take place in the dislocated site: that is,

something akin to the meeting of multiple streets and the subsequent

forming of place in the city. it is the mechanization of what we have

observed to be a natural phenomena.

The new park functions, by extension, are designed for meetings at

multiple levels, and are intended to charge the area with popular use.

They are inspired as much by the Jamaican's adroitness insport, and flair

for the theatric, as by the history of the park as a sports ground, and

reinforce that type of activity with a layering of new sporting venues. A

jogging and riding course, football (soccer) field, running track, tennis

courts, volleyball and basketball courts not only offer opportunities for

informal gamesmanship, but are attractive to the cross-section of the

public which prefers the fraternity of spectating at larger national events.

The variety of court surfaces also mediate the different scales of park,

block, sidewalk and building lot. The football green could double as an

outdoor theater for public meetings, celebrations, and concerts, ultimately

providing a space for the climax of yearly Carnival and Festival parades.

Money-football isan informal one-on-one game played with change on desktops;

the Manning Cup isthe pinnacle of schoolboy soccer tournaments.

39

-Ir,

~

&0

lD~

k,(

KAI

AC*()

O4uLx4(

1. 211

XAikN

~tit

f2.2.1

40

Notebook.

14

I2

Completing the 'cultural infusion' of the park is a Museum of National

Heritage, w ich, by virtue of its unique location in the new sports/cultural

park, w'l encourage the concentration of exhibitions and scholarly

infor ation relating to Jamaican culture, history, and civics. It would

p vide the prime opportunity to house both the bureaus and galleries of

the Institute of Jamaica, now in disparate locations across Kingston. This

will allow more efficient administration of the Institute's vast reserves, and

the more immediate access to them by the public.

Urban Moves, r One-One Cocoa...*

!

The relationship f the new functions to the city are established through

the overlap of ol

nd new ordering systems. The boundary of the park is

seen no more a divid r, but as the place common to both park and city

where activitie

through whic

presencing

a

/

t

__1E

takes place. Therefore, the park begins a new

the city ou side of the oval perimeter. The city, or more

ark. The p sent edge of the park is softened, its boundary

u

blurre

and peo

wed to filter back and forth, thus changing its

ter as something unto itself and subsequently, the present

apprehension of the space by the public.

The precise strategy lies in a re-visitation of the present ordering system

of the park: It consists of an East-West axis/path on which the National

F

Monuments are placed, which intersects at its centre (site of the War

(7

f 2.2.2

efracti

te the city plan, s likewise the generator for formal movement

char

I

f bot are regulated - almost as a transparent medium

The proverb "One -one cocoa full basket" means that every little bit eventually

The Urban Idea.

s.

.-

41

K

f2.2.3 Aerial View of Central Kingston, today.

-A

f 2.2.5 a,b &c

Progree Ske

g9

mmm

/K

1

3

I ta

I

Vp

I

f 2.2.4

F

L.

b

Overlay Showing Connection of Public Nodes( Park Presence inCity)

(I

f 2.2.6

Overlay Showing City

Presence inParke.

/

p~

4-

9

Ql

.~

Memorial) with a North-South perpendicular. As indicated before, the

design succeeds in nothing more than a local quartering of the park, and

I

1

its screening of public activity. In light of the benign quality of the present

reationship the logic of a formal connection is appropriated with much

servic tp ielf: in a ruder intrusion through the urban fabric.

-fter

e g ometry outside of itself achieves symbolic and practical

kewing

ends: 1) By t ing exception to the old order and freshly breaking its

perimet

emory of the park enclosure is heightened. 2) Pedestrian

,

fun eled along the axes from city to park, and vice-versa. 3)

activ

This a ivity eates the impetus for the reclamation of blighted lots with

ei tr

or the formation of smaller urban parks/playgrounds

al

th

to the park.

e

responds to the angle of incidence of King Street, formerly

the c'

thoroughfare, with the park. King Street ties the Parade to

Ahe

and is still a hub of commercial and official activity, but

s it

g -Anthus its connective potential within the larger city -

n6rth o

wntown, where it swerves to the right and comes to rest

uncerer dniously at the park perimeter. With the establishment of a

rec 1 a

pres

ri

o te park, the old street recaptures some of its

bric and connects the park with the historical city

I

h,

path extends North of the park creating a public

d Water Commission lands upwards to the

pro

Camp Road an

ingst

.

cam Avenue, cultural district of

In the West-East direction, continuing the axis of the

monuments out into the city, a green belt joins existing public nodes such

s Trenc

ewish Cemetery, Emmet Park, Sabina Park

47

Si

D.

-

AY L

f 2.2.10

f 2.2.9

Nature Meets Architecture - Cultural Training Centre, St.Andrew.

48

q

Layering of Activities,

and finally the Alpha Institute. The dimension of the city grid (150'x350') is

allowed into the zone of the monuments and is used to organise new

formal gardens in a broad swath crossing the park. Thus, they are seen

as belonging to the city. The potential would exist to create new

monument sites within the new order.

The skew and extension of the axes and their accidental meetings with

the park's extant geometries in tum produce opportunities for new pockets

of activity at the interface of park and city. These are populated with, to

f 2.2.11

Clock Tower, Old Harbour Square.

use Rowe's succinct term, "set pieces", which act as backdrop, evoke

historical association, redefine the character of the park, and create for it

the image it badly lacks. These are as follows:

Bleachers/Sports Area - placed with two sides common to both axes inthe

quarter previously inhabited by the old running/cycle track. Circulation is

continuous along its perimeter, allowing filtration of larger crowds through

its porous infrastructure from the street/park level and an elevated

walkway. Ceremonial entryways align with two minor city streets, the grid

of the new formal gardens, and the old axis toward Wolmer's School*.

f 2.2.12

Colonnade, Port Antonio.

Lockers, showers and other support facilities at its western rim are

wrapped ina curving wall which mimics the hard edge of the old Guinness

C

boxing gym, itself grafted to the ghostly foundations of the race-course

grandstand before it. Buffering the bleachers from the street are the ball

courts and parking areas, accessed by the winding appendage to King St.,

the only vehicular path through the park.

f 2.2.13

Facade - Ward Theatre, Kingston.

One of the most prestigious secondary (high)schools inJamaica, it was first

established in1729 for sons of gentry. Now comprising a girls' school, it has sat in

its present location at the Park's north edge since the late 19th century.

49

6J9~~~~

_VjK

94

4

4

j-

-'----------

7;

f

g/

4

I

-i./

.'

-A

)

(

"K

//

6

/kmr

/

a

/7

mi

/

~k

4

Min-

NN./L

I

7-7

/12

N'

rp

~4jM

.141

~~

~

~12

~

i 4~-'*lt~i

V

""I -

/

Ur

f2.2.15 a, b,c & d Imprssions.

a

b

North Entrance - intersection of the new promenade with the park's

northern curve (with which the erstwhile parish boundary of

Kingston/St.Andrew is coincident). Its proximity to the Wolmer's campus

suggests that a school-related activity make the transition to the park. An

horticultural garden is proposed: students may engage inits planting and

maintenance as a supplement to their biology curriculums. The operation

recalls the historical land use of the Liguanea Plain for cultivation, and

would ideally become an informational showpiece of tropical botany for the

public at large.

Old East Gate - a tower straddles the promenade to close the visual axis

of Torrington Road. It is associated both with the lookouts perched above

colonial Kingston for her defence and the iconic clock tower*, an inevitable

and beloved feature of the Jamaican town square. In deference to the

latter, the ground plane beneath it becomes the 'plate' for a sundial. The

tower itself is the style, the shadow casting object. It will be an

immediately recognizable marker for the place from any point in the city.

East Entrance - formal point of entry to the gardens from the city. Again, a

porous, habitable wall alters its own perception from that of barrier to

threshold. Options for the pedestrian are many: he or she might sit along

its cool stone surface; buy refreshment from a vendor; or cross into the

park via the extended city street or 'peopleduct', an elevated walkway

which weaves through the site, offering the characteristic roof view at

public events.

The saying "Born under the clock" isa true Kingstonian's expression of pride at

being born smack inthe middle of town.

53

f 2.2.16

Sketch.

f 2.2.17

f2.2.18

Sketch.

f 2.2.19

54

Model View (South, towards Downtown).

Model View (South, from Torrington Road).

South Entrance - this existing patch is an anomaly of the park proper,

acting like an appendage which pokes into the denser fabric of downtown.

Its centerpiece is an aged fountain. There, a corral is defined by rough

earth and bordered by stables and a riding path. This could be considered

a starting point for horseback rides around the park, and even into the city

itself. Thus, the park function would come full circle, intensifying

association with the tree-lined perimeter where thoroughbreds once ran.

West Entrance - nucleus of the project, where King Street, the park

perimeter and the axis of monuments converge, and the mixing point of

vehicular and pedestrian traffic - thus the prime location for the main

function space, the Heritage Museum. It is conceived as a regulating

'field', a container for the collision, and to some extent the choreography,

of these various forces. An orthogonal grid of structural columns is

chosen both for its brevity and flexibility in encompassing multi-functional

space, but also is associated with its natural setting: It evokes the

coolness of a grove of cultivated trees, an integral feature of the Jamaican

landscape.

To that end, the whole is shaded by an overextended

horizontal - the roof of this 'forest'.

The rationality of the gridded plan is countered on the interior by shifting

planes responding to the deluge of directional thrusts. While the structure

is largely indifferent, the space within is active and energetic. The floors

are not clearly separate, for the transition from outside through the

building is made via a series of ramps and intermediate planes, which

eventually soar beyond the park and over the street, continuing the

journey on the other side.. The building 'cracks' down its centre, allowing

vegetation and natural light to infiltrate.

55

f 2.2.20

Building Studies, sketches.

f 2.2.21

Building Studies, models.

The planar quality of the facades enhances the notion of breaking

barriers and crossing boundaries. They differ outwardly mainly to draw

attention to the separate zones of the city which they front: on the North,

to the park and suburb, it is softer and more pervious, made with screens

and columns; to the South and the downtown is turned a tougher, more

resilient face.

These are the first and last(ing) impressions of the motorist or pedestrian,

on their journeys to and fro the city and suburb, in and out of nature and

artificiality. Inside, the facades are revealed for all their flatness, and the

gravity of the scene outside descends, as only one who has had the

privilege of a backstage tour can appreciate. Outside, there are so many

people different from ourselves, tossed together in a marvelous mix of

colour, but barely mindful of one another, too busy to notice; moving

amongst, but not with, the next man.

f 2.2.22 b

East Facade.

Inside, there are only people like us, come to learn a little bit more about

Jamaica, about each other, meeting under a giant beam of sunlight, in the

park.

f 2.2.22 c

Norlh Facade.

57

T-

p at

U-

* L---Aw--A L-, -, L i

I

f 2.2.24

58

At the Intersection, montage.

--------

1~1

V

L

~ ~

-

-

f 22.25

At the Intersection, oved

Conclusion: A Full Basket?

The last remaining cocoa is the addition of people to the mix. This would

necessarily involve the projection of the thesis into reality, a liberty I take

for the sake of discussion.

Nothing, a Jamaican would muse, rubs his countrymen the wrong way as

much as the figure of authority commanding their actions and interfering

with their steadfast daily routine. This is why the thesis sets out guidelines

for action in reclaiming the park from its exile - why it does not attempt to

specify every moment, preferring for the enabling quality of the design to

be augmented by and have its gradual effect on the community. Having

introduced a framework conceived in the pluralist spirit, and indeed

derived from latent historical orders, it is left to see what the will of people

can accomplish in re-taking, and keeping their public place. Having given

an impression, I, as architects often do, await expression, the reaction and

critique by the user. This is ultimately what gives it a life, as when the four

walls of a house are embellished by the human touch of its occupants. In

Jamaica, this iswhat gives it permanence, if anything may be called so in

our modern existence. It is with a sincere belief in the potential of

architecture to so empower individuals, and a confidence in the Jamaican

dynamic to affect social adjustment, that I offer this work.

61

62

63

64

Selected Bibliography

Bardi, P.M. The Tropical Gardens of Burle Marx. New York: Reinhold

Publishing Corporation, 1964.

Bedard, Jean-Francois, ed. Cities of Artificial Excavation: The Work of

Peter Eisenman, 1978-1988. Montreal: Centre Canadien d'Architecture/

Rizzoli International Publications, 1994.

Berman, Marshall. All That is Solid Melts Into Air: the Experience of

Modemity. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1982.

Black, Clinton. A New History of Jamaica . Kingston: William Collins and

Sangster Jamaica Limited, 1973.

Curtin, Marguerite, ed. Jamaica's Heritage: an Untapped Resource.

Kingston: The Mill Press, 1991.

Dolan, Winthrop. A Choice of Sundials. Brattleboro, Vt: S.Greene Press,

1975.

Higman, B.W.

Jamaica Surveyed. Kingston: Institute of Jamaica

Publications Limited, 1988.

Johnson, Anthony. Kingston: Portrait of A City. Kingston: Tee Jay

Limited, 1993.

Manley, Michael. The Politics of Change: A Jamaican Testament.

London: Andre Deutsch Limited, 1974.

Nettleford, Rex, ed. Jamaica in Independence: Essays on the Early

Years. Kingston: Heinemann Publishers (Caribbean) Limited/ London:

James Currey Limited, 1989.

Nettleford, Rex. " Emancipation, Independence Through the Arts." The

Sunday Gleaner (Kingston), July 31, 1994.

Norberg-Schulz, Christian. Architecture, Meaning and Place. New York:

Rizzoli International Publications, 1988.

Norris, Katrin. Jamaica: the Search for an Identity. London, New York:

Oxford University Press, 1962.

Reps, John W. The Making of Urban America: A History of City Planning

in the UnitedStates. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965.

Rowe, Colin. Collage City. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press,

1978.

Tschumi, Bernard. Event-Cities. London, England/ Cambridge,

Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1994.

Zach, Paul, ed. Insight Guides: Jamaica. Singapore: APA Publications

(HK) Limited, 1993.

65

66

Illustration Credits

Illustrations are by the author, except as noted:

1.1.1

Zach, Insight Guides: Jamaica., p.21.

1.1.2

Johnson, Kingston: Portrait of A City, p. 43.

1.1.3

Johnson, p.v.

1.1.4

Reps, The Making of Urban America: A History of City

Planning inthe United States, p.7.

1.1.5

Reps, p.14.

1.1.6

Higman, Jamaica Surveyed, p.160.

1.1.7

Higman, p.252.

1.1.8

Higman, p.90.

1.1.9

Higman, p.282.

1.1.10

Higman, p.219.

1.1.11

Higman, p.287.

1.1.12

National Library of Jamaica photograph, # N/I 5783.

1.1.13

Jamaica Survey Department Map.

1.1.15

Shell Company Road Map of Jamaica (Kingston: Macmillan

Publishers Limited, 1985, 87, 89).

1.1.19

Programme of The Opening Of Parliament 1994-95 ( Kingston:

Jamaica Printing Services Limited, 1992), p.1.

1.1.21

Zach, p. 128.

1.2.1

Daily Gleaner ( Kingston) article, from Nat'l Library ( Tom

Redcam Ave.) Collection on National Heroes Park, date and

page no. indiscemible.

1.2.2

Based on Survey Dept. Map of 1958.

1.2.5

National Library photograph, # N/381 1.

2.1.4

Zach,p. 129.

2.1.6

Zach, p. 266.

2.2.3

Survey Department aerial photograph, 1988.

2.2.8

Johnson, p. 88.

2.2.11

Zach, p. 188.

67