North Carolina State of the Workforce: The North Carolina Commission on

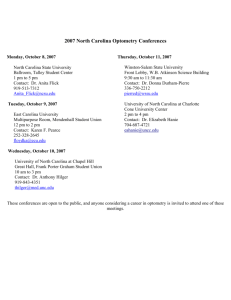

advertisement