Paper Catechistic Teaching Revisited: Coming to the Knowledge of the Truth

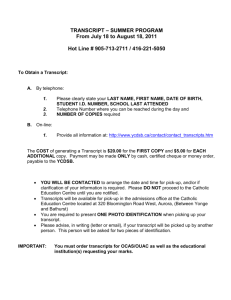

advertisement