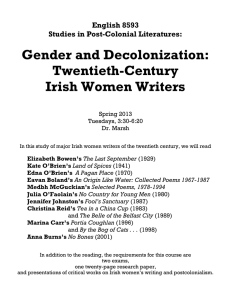

Paper Enoughness, accent and light communities: Essays on contemporary identities

advertisement