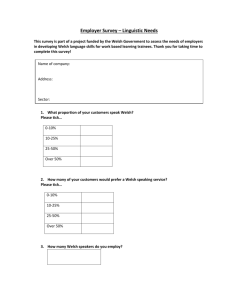

Paper diversity Bonnie Urciuoli

advertisement

Paper The compromised pragmatics of diversity by Bonnie Urciuoli © (Hamilton College) burciuol@hamilton.edu March 2015 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/ The compromised pragmatics of diversity Bonnie Urciuoli Anthropology Department Hamilton College Clinton NY 13323 burciuol@hamilton.edu Paper delivered at Georgetown University Round Table (March 6, 2015) Panel: "Discourses of Diversity" Organizers: Zorana Sokolovska and Alfonso Del Percio Abstract. The referring expression diversity has become routine in organizational discourses, where it is treated as a concrete measurable category. It is better understood as an emergent property of the interplay of markedness and unmarkedness within a structured set of social relations, and in relation to a more general context. People’s experience of markedness within a social formation is chronotopically organized, taking on meaning in particular times and places. At the same time, generalizing markedness as quantifiable units of diversity makes it possible to eliminate that experiential specificity, disconnecting diversity from context and making it available for use toward other organizational aims, such as institutional promotion and branding. Once disconnected from the structural properties that give rise to the experience of markedness, diversity can be connected to neoliberal agency and treated as a constitutive element of individuals. In a market-saturated social world, diversity discourses (especially where quantifiable) can be good for an organization’s bottom line. To illustrate this point, I offer the parallel cases of discourses of social diversity in undergraduate liberal arts education, and the touting of linguistic diversity in corporate or government discourses. I show that that disconnection is never quite easy: diversity alone rarely seems to carry enough promotional punch. Marketers routinely connect notions of social and linguistic diversity to readily neoliberalized notions of skills, leadership, innovation and authenticity, all of which can be found in higher education and corporate discourses. But while skills, innovation, and so on can easily be cast discursively as something that the individual (as student or worker) “has”, diversity itself never quite manages to shake its structural underpinnings, is never quite disconnected from the particular lived time/space-bound envelopes of relationship and life experience-based realities of those considered diverse. Short summary (50 words) Diversity is routinely treated as concrete and measurable, but it is an emergent property of markedness relations, lived and meaningful in particular times and places. Though marketed in relation to neoliberalized properties of individuals (skills, innovation, authenticity) diversity’s marketing potential is always compromised by the echo of lived experience. 0 Language skills are obviously needed in today’s increasingly global economy--and diverse workers often have this proficiency. If a company needs specific knowledge or language skills, it may hire foreign nationals for help. In some markets, international job seekers have the advantage. For example, companies breaking into European, Asian or Latin American markets will need foreign expertise. High-tech firms in particular are expanding into countries abroad. In the United States, we like to believe that English is “the language of the world.” While that may be true for business, our native tongue ranks second in the world behind Chinese and just slightly ahead of Hindustani. To truly build relationships with the other people of the world, we must speak their language. It is a tremendous advantage of workplace diversity if we enable people from other cultures can help us understand not just their words, but also the meaning behind what they are saying.i In their 2011 discussion, Jan Blommaert and Ben Rampton outline the tension between entrenched notions of named, bounded languages and the assorted dynamics pulling social configurations and experience of speakers in complicated directions. This latter dynamic reality is pretty much the opposite of the kind of thinking about language difference that typifies that opening quote. As is typical of business notions of diversity, whoever wrote it presupposes the isomorphism of named language, named country, and named ethnicity -- not surprisingly, given the ends to which ‘diversity’ is imagined as a corporate-friendly value. Such imagining necessarily excludes consideration of how the various elements making up whatever is considered diverse came into existence, that being especially problematic. Linguistic diversity is necessarily imagined as the capacity to use different languages as a skill set. That imagining generally excludes the chronotopes that frame people’s experience of those languages. Whatever elements of identity possibly affiliated with such language experience get repackaged as some kind of accompanying skill set. This neoliberalized reimagining of language, the subject of much recent work, forms one end of the profit-pride polarity outlined by Heller and Duchêne (2012), contrasting language speaker as worker with language speaker as ethnic citizen. The notion of that worker has been developing since the 1990s as a “bundle of skills” fitted to the needs of the work place, an imagining now routine in corporate discourses (Urciuoli 2008). The literature mapping out that worker has become accepted wisdom in human relations discourses. In it, 1 worker diversity is understood as those personal characteristics (soft skills) or forms of knowledge (hard skills) that provide ‘value added’ to their employers. At about this time, Jaffe (2007) argues, a parallel paradigm emerged in which language difference came to be similarly imagined as ‘value added.’ Barakos (2012) provides an excellent example of this in her discussion of the decline in Welsh speaking among northern and western rural populations and the rise in Welsh speaking among urban businessmen in Wales’ Anglicized south. Welsh language policy, she notes, is designed to be both promotional (advance the status of Welsh, endorse bilingual corporate identity, show symbolic cultural commitment) and to operate as a “grassroots tool for regulating modes of interaction” (p. 174). Along comparable lines, McEwan-Fujita (2005) addresses the way neoliberal language planning in Scotland has run along lines dictated by funding principles and economic goals, excluding from consideration any minority-language planning based on sociolinguistic or linguistic anthropological or any other relevant social science principles. Not that such language planners are likely to be remotely interested in anything that social scientists have to say. The kind of language planning and policy that Barakos and McEwan-Fujita describe and that many other ethnographers have examined, including contributors to the Heller-Duchêne volume, is done with an eye toward reimagining difference as a form of human capital. The problem with imagining language is part of the larger problem of imagining social diversity: what is language imagined to be, by whom, and to what end. The key difference is whether a social formation is construed with an eye toward accurately accounting for what actually exists, as is the case with social science notions of diversity and superdiversity, or whether it is construed with an eye toward maximizing profit somewhere along the line. The former – paying attention to what actually exists – sees a generation of demographic complexity, in which never-settled categories of difference are continuously 2 produced. The latter – imagining difference as categories of human capital to enhance corporate gain – necessitates the design of categories that are sharply distinguished from, but quite comparable to, one another. Such categories involve a template of elements by which any one employee can be compared to any other employee. Each of those elements must have some identifiable utility and also must be measurable or assessable in some way. Their value also depends on some degree of macro-micro isomorphism, the individual being identifiable with the group in some defining way. To that end, they partake of those qualities that Irvine and Gal (2000) describe as iconization and erasure: people who represent a category must in some way iconize it, and variation among different representatives of that category must be regarded as unimportant. Such a template is readily supplied by consultant Marilyn Loden (1996), who has provided the go-to blueprint cited endlessly on websites within and outside the U.S.ii Loden proposes a model of diversity made up of primary and secondary dimensions of each individual’s social constitution, the most recent version listing nine primary and eleven secondary dimensions. The primary dimensions (age, race, ethnicity, sexuality, income, spiritual beliefs, class, gender, physical abilities and characteristics) are those which Loden finds “. . . particularly important in shaping an individual’s values, self-image and identity, opportunities and perceptions of others. We think of these primary dimensions as the core of an individual diverse identity.” The secondary dimensions (first language, family status, work experience, communication style, cognitive style, political beliefs, education, geographic location, organizational role and level, military experience, work style) represent “essential dimension of an individual’s social identity.” Each of these identity dimensions constitutes an element contributing to a whole worker. Note the parallel between language and ethnicity/race in this model, as two among many diversity dimensions possessed by the worker. 3 In this model, the speaker is not a person so much as a skills bundle, each of which exists as a category by virtue of its capacity to be counted as an enhancement of human capital. What counts as human capital exists in a hierarchic relation to some larger end, shaped by company or national policy or both. Barakos provides a detailed account of this as she describes the shift from the 2003 Welsh national language policy focused on language choice and establishing the equal status of Welsh and English in public agencies and administration to the 2012 national policy focused on “promotion and persuasion” (2012:171). Thus neoliberally restructured, the value of Welsh becomes measurable in some sense of return on investment such as its capacity to extend service provision and enhance the experience of customers, and Welsh speakers gain value to the extent that they can facilitate those ends. More broadly, the end is private sector efficiency or expansion, the means (one of many) is the use of Welsh, and the vehicle by which that means is delivered is the speaker. In other words, speaking Welsh and identifying as Welsh cannot be enough unless they are justifiable in ROI terms. So why should this be a problem, if the goal is to promote acceptance of difference? Shouldn’t there be an allowable range of methods to effect such promotion, and isn’t it impractical and purist to think otherwise? Well frankly no. When ‘diversity’ is processed in these comparably quantifiable ways, as worker-means-to-corporate-ends, the discourse is not about accepting difference but about using it in ways that have little to do with the human beings involved. With the shift to commensurability as a means to an institutional or corporate end, difference as such ceases to exist, or rather what ceases to exist is the condition of markedness that led to the emergence of difference in the first place. The linguistic and social distinctions (understood as the referents of diversity) are best understood as emergent properties. They reflect an interplay of markedness and unmarkedness qualities in historically situated, economically and socially structured 4 relations. The experience of markedness is chronotopically organized within such formations, as noted by Dick and Wirtz (2011:E7) drawing on Silverstein (2005, after Bakhtin). The experience of difference is linked to relationships, contexts, times, places, in specific configurations growing out of discursive interaction linking present and prior discursive events to each other and to discursive types recognizable to those sharing common qualities, in this instance, qualities of markedness – the more marked, the more shared. The more forms of differentiation emerge, the more people are likely to experience chronotopically complex relations. Since chronotopicity is a function of the properties structuring people’s social worlds, it is never fixed. People’s experience of it can range from the relatively stable to the very complex and fluid, as must be entailed by the experience of the superdiverse. None of the distinctions that emerge from such processes are readily susceptible to the kind of fixed, commensurable classifications that constitute institutional and corporate diversity discourses. In fact such discourses operate independently of any chronotopically specific experience except in the most emblematic and generalizable way. But then again, the whole point to corporate and institutional diversity discourses is to get rid of all that messy experiential specificity. Not only is it useless for measuring ‘added value,’ but the whole point is to disconnect diversity from context and connect it to neoliberal agency as a constitutive element of individuals. This is readily seen in the practices and policies by which the Posse Foundation recruits cohorts of ‘diverse’ students into colleges and universities. Posse promotes its recruits as agents of change, a “new kind of network of leaders” reflecting “the country’s rich demographic mix”: “The key to a promising future for our nation rests on the ability of strong leaders from diverse backgrounds to develop consensus solutions to complex social problems.”iii Posse presents its outcomes in ways countable as units of measurement, such as who goes on to graduate or professional school 5 and who has what scholarships. Thus, the notion of students acting as change agents is made manifest as measurable accomplishments: the higher the numbers, the more this can be read as a form of social change. Projecting success onto countable outcomes is not necessarily the same as actual structural change, but that may be less important than the intended rhetorical impact of such ‘outcomes’ as a promotion of neoliberal values. What counts here is the affiliation of diversity with other elements of neoliberal agency (Gershon 2011), wherein every constitutive element of self is valued by its deployability, as if one ran oneself like a business. Diversity as simply racial identity or knowledge of a language is not enough to constitute value but such identity or knowledge can enhance the value assigned to neoliberal typifications of valued human capital like leadership, changemaker, and other ways of casting individual value as the capacity to contribute to an organization, and for pretty much the same reason that Welsh has been redefined as a valued language because of its capacity to “promote and persuade” otherwise unreachable markets. Knowing a language cannot simply be good in and of itself, it must be deployable in the act of communication, i.e. as part of a skill set. Thus, as Heller (2003) and Roy (2003) have shown, the use of French in Canadian call centers reinforces a shift in social meaning away from a user’s ethnic identity and toward neoliberal subjectivity defined by possession of skills. Such deployment of language as a skill requires considerable disciplining of linguistic production: in the case of call centers it is tightly scripted and the speaker is rarely the author of the script. The language itself would be used with attention to a generic standard, or the playing off of standard and non-standard as in Duchêne’s (2009) study of Swiss multilingual operators deploying major languages in standardized ways while using non-standardized local languages to provide touches of authenticity. In the same way, deployment of social markedness such as racial difference operates within a frame of neoliberal value. To return to the Posse example, students who enter 6 college through Posse are continually channeled toward highlighting aspects of self that the institution will best value. They are also more likely than unmarked students to be tapped to contribute to the institution’s brand, highlighting the fungibility of diversity’s representative units. Diversity in higher education is notoriously a numbers game, and much of the value of ‘diverse’ students lies in students’ capacity to provide content for given categories of distinctive difference: N% of each category playing its role in the mosaic of public presentation, accompanied by a mosaic of faces on institutional visuals. Any diverse student can replace any other diverse student in this representation. This structuring extends to the kinds of campus participation roles in which such students routinely find themselves, running the ‘diversity’ organizations, serving on campus committees, and variously representing the institution. Such participation can become grueling (Childs, Nguyen and Handler 2008). And while racially marked students often seek each other out to find comfort in chronotopically linked experience, that experiential residue has little value in and of itself (unless of course it can be turned into some kind of institutionally promoting product purveyable on its website). Yet for those students, like the speakers who supply ‘diverse’ languages, that experience is what makes their identity or their language real. In institutional and corporate discourses, diversity is less a referring expression than a pragmatic device indexing an organization’s orientation to a particular set of neoliberal values -- values which, ironically, exclude in too many ways the best interests those who actually “bring” diversity to that organization. References Cited Barakos, Elisabeth. 2012. Language policy and planning in urban professional settings: bilingualism in Cardiff business. Current Issues in Language Planning 13(3): 167186. Blommaert, Jan and Ben Rampton. 2011. Language and Superdiversity. Diversities 13(2): 1-21. Childs, Courtney, Huong Nguyen, and Richard Handler. 2008. The Temporal and Spatial Politics of Student “Diversity” at an American University. In Timely Assets: The Politics 7 Of Resources and their Temporalities. Elizabeth Emma Ferry and Mandana E. Limbert, eds. Pp. 169–190. Santa Fe NM: SAR Press. Dick, Hilary Parsons and Kristina Wirtz. 2011. Racializing Discourses. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 21(S1):E2-E10. Duchêne, Alexandre. 2009. Marketing, management and performance: multilingualism as a commodity in a tourism call center. Language Policy 8(1):27-50. Gershon, Ilana. 2011. Neoliberal agency. Current Anthropology 52(4): 537–55. Heller, Monica. 2003. Globalization, the new economy, and the commodification of language and identity. Journal of Sociolinguistics 7(4): 473-492. Heller, Monica and Alexandre Duchêne. 2012. Pride and profit: changing discourses of language, capital and nation-state. In A. Duchêne and M. Heller (eds.) Language in Late Capitalism: Pride and Profit. London: Routledge. Pp. 1-21. Irvine, Judith and Susan Gal. 2000. Language ideology and linguistic differentiation. In Paul Kroskrity (ed.), Regimes of Language: Ideologies, Politics, and Identities. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research. Pp. 35-83. Jaffe, Alexandra. 2007. Minority language movements. In Monica Heller (ed.) Bilingualism: A Social Approach. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Pp. 50-70 Loden, Marilyn. 1996. Implementing Diversity. Burr Ridge IL: MacMillan. McEwan-Fujita, Emily. 2005. Neoliberalism and minority language planning in the highlands and islands of Scotland. International Journal of the Sociology of Language 171: 155-171. Roy, Sylvie. 2003. Bilingualism and standardization in a Canadian call center: challenges for a linguistic minority community. In R. Bayley and S. Schecter (eds.), Language Socialization in Multilingual Societies. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters. Pp. 26987. Silverstein, Michael. 2005. Axes of evals: Token vs. type interdiscursivity. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 15(1): 6-22. Urciuoli, Bonnie. 2008. Skills and selves in the new workplace. American Ethnologist 35(2): 211-228. i http://www.ethnoconnect.com/articles/9-business-advantages-of-diversity-in-the-work-place accessed 2/24/15 ii http://www.loden.com/Web_Stuff/Dimensions.html accessed 2/16/15 iii http://www.possefoundation.org/about-posse/why-posse-is-needed accessed 2/18/15 8