Course Correction Reversing Wage Erosion to Restore Good Jobs at American Airports

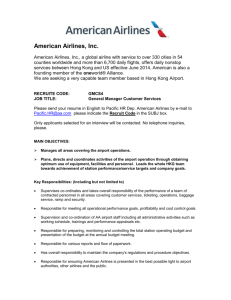

advertisement