FREE FORM IN of plasticity in architectural design

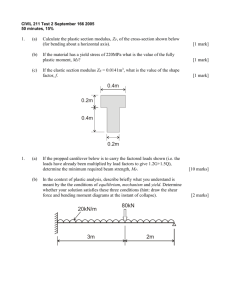

advertisement